Athens, Ga. – Food deserts—a term used for geographical areas where healthy food is inaccessible or prohibitively expensive—are connected to high rates of obesity and diet-related diseases. A new University of Georgia study says that smaller and mid-sized retail stores may be the best solution to shrinking these deserts.

Solutions to food access problems previously have focused on the proximity of food sources to housing in low-income communities and neighborhoods. Residents’ actual daily activities and buying habits, however, have received little attention.

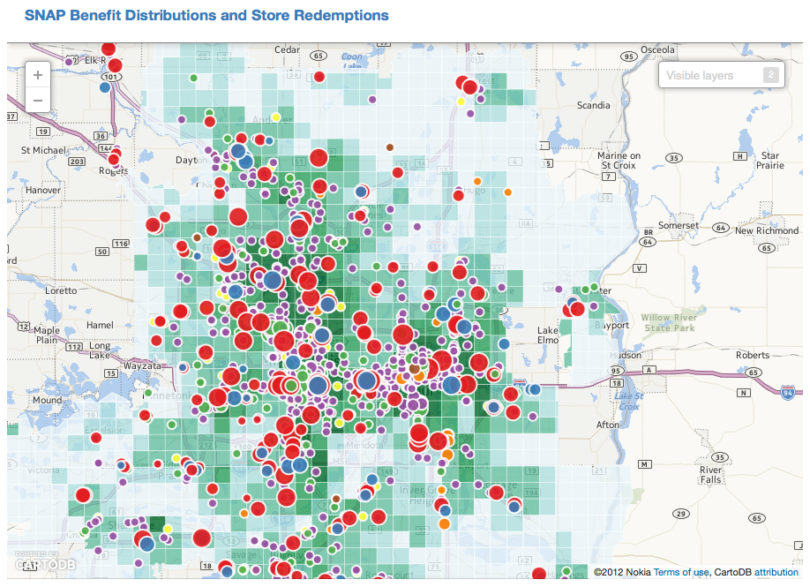

To develop a better understanding of how and where food-buying resources are spent, UGA researcher Jerry Shannon has combined on-the-ground interviews with information from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, commonly known as SNAP.

Shannon, a temporary assistant professor in the UGA Franklin College of Arts and Sciences department of geography, authored the article, “What does SNAP benefit usage tell us about food access in low-income neighborhoods?” published in the April print edition of the journal Social Science and Medicine.

The concept of food deserts grew out of a need to describe areas with the combination of a low-income population and reduced availability of stores selling healthy foods, such as fruits and vegetables. Online resources made available by the USDA identify food deserts by measuring the distance to the closest supermarket from each census tract. Coupled with income, if more than 33 percent of a population in a given area lives more than a mile away from a supermarket, that is considered a low-access area.

“For geographers, that definition is problematic, because the perception of distance can change-something can be far away but feel close if you have a car, for example,” Shannon explained. “Access to healthy food is a question of resources and daily mobility as well as proximity.”

Food deserts straddle development, politics, economics and transportation issues; one solution used in many localities has been to introduce a new supermarket or big box store into a low access area. Shannon’s research and related case study suggest a different development alternative may be more effective.

One primary finding documents how low-income people access the food system and confirms that people do not only shop where they live.

“People aren’t only shopping in their neighborhoods, and even within those neighborhoods, nearby supermarkets did not make up as much of the total SNAP business as they did out in the suburbs,” he said.

Shannon conducted his research in the Twin Cities area of Minneapolis-St. Paul in Minnesota.

“Decisions about where to shop are based on a variety of factors, including social networks, perceptions of quality and available transit options,” he said.

As one part of his research, Shannon analyzed two neighborhoods in Minneapolis, conducting 38 interviews and tracking the movements of subjects using GPS-enabled cell phones to record where they went during the course of the day, the places where they purchased food and the reasons why they stopped to get food or added food shopping to a trip.

“It makes the problems of food access or food deserts more closely tied to broader issues of the kinds of development needed in urban neighborhoods, in particular,” Shannon said. “It’s not so much a problem of ‘let’s just create a new supermarket’ as one of ‘how do we design neighborhoods that are accessible and livable for all parts of the population?'”

Shannon suggests smaller retail outlets and farmers’ markets as potential solutions, but also that they must be tied to transit-related infrastructure to assure access across the given population of any area.

“The big question is, how do you weave healthy food into what is already the daily rhythm of people’s lives and the ways they are moving around in the city?” he said.

An interactive map of Shannon’s data on how SNAP benefits are used is available below and at http://jerry.shannons.us/initial-research-results-online-data.html. The journal article is available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953614001257.