International travel isn’t an option for most students in Mary Claire Giddens’ freshman English class at Fitzgerald High School. Even though they live two hours from the Atlantic, some of them have never seen the ocean, much less crossed it. Fitzgerald, about 30 miles northeast of Tifton, is best known for the wild Burmese chickens that strut the downtown streets and, some claim, keep the bugs away. It is a heavily agricultural community with a population under 9,000 and a poverty rate of 38.8 percent (Georgia’s average is 16.9 percent). For some in the town, exploring new places isn’t possible.

But one warm May morning, just a few weeks before the end of school, Giddens takes her students far away from their sleepy hometown, over the ocean, and back a few centuries to Italy’s fair Verona with William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

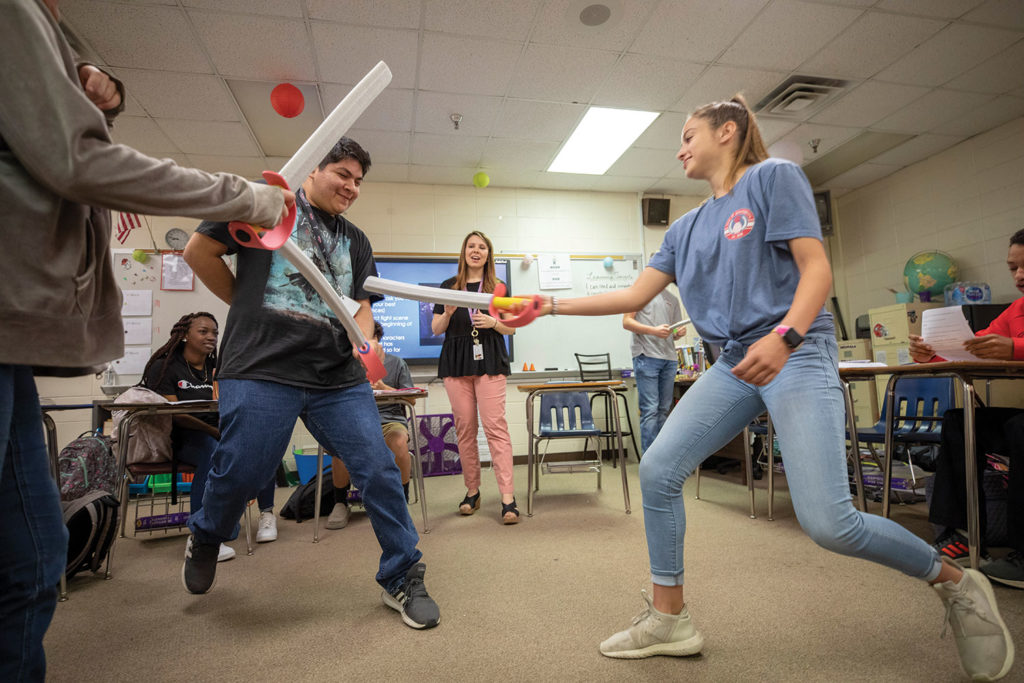

After graduating from the College of Education, Mary Claire Giddens BSEd ’14 returned to her rural roots to teach in Fitzgerald, Georgia (Photo by Peter Frey/UGA)

Capping the year with a play written in Elizabethan English could be a tough sell, but Giddens BSEd ’14 keeps the room engaged with a little dueling (as she has the students act out the fight scenes with foam swords) and an accessible dive into the text. Even though the story is hundreds of years old, Giddens keeps it relevant, comparing the earnest lovers to friends they might know while simultaneously cultivating an appreciation for Shakespeare’s writing.

“I want y’all to pay attention to what smooth game Romeo has,” Giddens says when the class reaches the scene of the star-crossed lovers’ first kiss.

The students eat it up. One remarks that, before meeting Juliet, a forlorn Romeo is acting “cringey.” Another questions whether the two are even in love, really. “He’s 17; she’s 13. They don’t know what love is.”

The skepticism is evidence that the students are paying attention.

In her second year at the school, Giddens is already the kind of inspiring teacher who can direct even the class clowns toward an appreciation for the Bard. She has become a lot like her own English teacher, Brenda Whitley, who teaches across the hall. It was about 10 years ago that Giddens was reading Shakespeare as a freshman in this same school from the same textbooks as her students. It’s one of the experiences that inspired her to earn a teaching degree from UGA’s College of Education.

Although she hadn’t really planned to, Giddens has come back to teach in her rural hometown. But this sort of homecoming has become an increasingly uncommon story.

Challenges and Solutions

Schools across the nation are facing a number of challenges. A big one is teacher shortages, says Denise Spangler PhD ’95, dean of the College of Education. In a 2018 Gallup poll of K-12 school superintendents, 61 percent said they were concerned about their district’s ability to recruit and retain quality teachers.

The challenges are especially acute for rural and urban schools (two areas associated with high poverty rates). But whereas policymakers often talk about the challenges of urban schools, rural districts tend to be forgotten. That’s also true in the scholarly realm, where there’s fairly little research about the dynamics of rural K-12 education—even though nearly one out of five students attends a rural school in the United States.

Sheneka M. Williams, associate professor in the College of Education, is one of the researchers exploring this issue. For Williams, the topic is personal as well as academic. She

Sheneka M. Williams, associate professor in the College of Education, is researching the dynamics of rural education. (Photo by Peter Frey/UGA)

grew up in rural Jackson, Alabama. It was the kind of town where her parents knew her teachers by name before she even started school. Williams rejects the notion that people from small towns are undereducated. For her, it was a quality learning environment. But she does see a growing problem: Too often, a rural community’s brightest minds don’t stay.

“Many are leaving, and those who do go off to college find it difficult to return,” Williams says.

What’s happening in rural communities is part of a larger economic shift.

“As the U.S. has transitioned away from relying heavily on manufacturing and goods production, it’s hit rural communities especially hard and sometimes created a cycle of unemployment,” Williams says.

The College of Education is addressing the needs of these rural communities not only through its research, such as Williams’ scholarship studying rural education, but also with its rigorous teacher preparation program, which equips aspiring teachers to educate a diverse array of students. The impact can be felt throughout the state. In the last five years, the college has supplied at least one UGA grad to teach in 153 of Georgia’s 181 school districts.

Building Community

But it’s not all bad news. K-12 education may be one area that—if fortified with good teachers and the right resources—can be a source of strength for a small community. “What rural areas can offer is a more cohesive community. It’s more familial. There is research that says these smaller learning environments, where you feel like you are part of a community, provide benefits for students,” Williams says.

Already, schools can act as the cultural heart of a community. A place where generations have shared experiences and have gathered for Friday night football games and school concerts.

That sense of community is what Chuck Arnold MMEd ’10, EdS ’13 is building as director of bands at Dawson County High School. A skilled trumpeter, Arnold served in the U.S. Navy Band overseas and worked as a freelance musician in New Orleans before becoming a school band director, just like his father.

Arnold came to UGA for his postgraduate work. While in Athens, he taught the Redcoat Marching Band trumpet section and acted as rehearsal director for the UGA Jazz Ensemble.

While a graduate student ay UGA, Chuck Arnold MMEd ’10, EdS ’13 taught the trumpet section of the Redcoat Marching Band and was rehearsal director for the UGA Jazz Ensemble. He is now director of bands at Dawson County High School in North Georgia. (Photo by Peter Frey/UGA)

After working at Collins Hill High School in Gwinnett County, Arnold went to Dawson County. He was drawn to two things: the beauty of the area (a tight-knit community nestled in the foothills of the north Georgia mountains) and the challenges that awaited.

When he arrived, the bands program was not in good shape. In a school where 1,100 students were enrolled, only 35 were in the band. The program had not been a priority in the district until a new administration arrived.

Arnold was charged with building a band that could be a point of pride for the community. He had his work cut out for him. Being a high school bands director is as much about running an operation (fundraising, travel plans, recruitment) as it is about teaching students to play together. Arnold’s coursework and experiences at UGA have been invaluable for helping him manage the load.

And for him, the effort is worth it. Music education, he says, offers an unparalleled experience to prepare students for success.

“It’s life in a nutshell,” he says of the band experience. “It teaches them accountability. They have to be here every single rehearsal because every other member is counting on them. You’ve got to be prepared. It’s very similar to job expectations.”

In his four years at the helm, the band has tripled in size and raised its music grade level from a 3 (which is a medium-skill level) to 5 (advanced). Arnold credits the students and the school administration for the developments. Others might add that Arnold’s musical experience combined with academic chops are a big factor too.

Distance Learning

While teacher shortages are a problem across the board, it is particularly acute in special education. Julie Rigdon BSEd ’18 was oblivious to the issue until 2011. That’s when a retinal disease damaged her husband Kevin’s vision so badly that he had to quit his job.

Julie Rigdon BSEd ’18 teaches visually impaired students in South Georgia. (Photo by Peter Frey/UGA)

To support her family, Rigdon went to work as a bookkeeper for an elementary school in Waycross. There she met the Ware County School District’s visual impairments teacher, Barbara Sonnier. Rigdon was still navigating her new life with a visually impaired husband. Sonnier helped Rigdon find some of the resources her family needed to get by. As Rigdon saw Sonnier working with students, helping equip them for a life without sight, Rigdon was inspired. She saw the need, and she wanted to help.

“There aren’t enough vision teachers anyway,” she says. “But in South Georgia, there are practically none.”

In her mid-30s, she enrolled in UGA’s online Bachelor of Science in Special Education program, a two-year degree that offers students the flexibility to complete this degree in a high-need field. In her area of southeast Georgia, bachelor’s programs are limited.

“It was not an option to drive to the nearest on-campus program because I needed to stay close to home for my husband and daughter,” she says. “Having the flexibility to be available for my family and get a degree from UGA was too good to not go for it.”

As soon as Rigdon graduated, she began working on her online master’s degree in visual impairment. This fall, she begins her first job as a visual impairment teacher in Wayne County. She’ll serve 11 students who range from 2nd to 11th grade, helping them learn Braille, making sure they have the right learning materials, and teaching them daily living skills (cooking, cleaning the house, and other daily tasks that they can’t learn from visual cues).

Getting to finally teach will be a relief for her. Just like Giddens, Williams, Arnold, and others who’ve come through UGA’s College of Education, the ultimate goal is helping the younger generations reach their potential.

“I’m so excited to finally get to work with the students and their parents,” Rigdon says. “Just to let them know, there is someone here that can help you.”

Theory vs. Practice

There’s an old debate in teacher preparation about the importance of theory (such as theories about how children learn, how to use technology effectively, how to teach reading) versus practical experience (just getting into a classroom and teaching). Both are extremely important to becoming an effective teacher, says Dean Denise Spangler, especially in a diverse environment.

The College of Education already is a national heavyweight when it comes to teaching theory and research. And it has worked to balance theory and practice with its partnership with the Clarke County School District. The Professional Development School District brings UGA students and faculty into Clarke County schools to contribute to the education of the K-12 students while also giving aspiring teachers an invaluable experiential learning opportunity. More than 500 UGA students participate each year, and eight faculty members serve as professors-in-residence to guide UGA students and provide support to teachers and administrators.

Mary Claire Giddens went through the program and calls it one of her most valuable experiences at UGA. She says the needs of urban students in a high-poverty area are comparable to those in her rural school.

“It gave me a realistic picture of what teaching was going to be like,” she says.

The program also sharpens the expertise of UGA faculty.

Denise Spangler PhD ’95 is dean of the University of Georgia’s College of Education. (Photo by Peter Frey/UGA)

“It helps them make sure that what we’re doing is relevant in today’s schools with the kinds of policies that teachers work under, the kinds of students they’re working with, the kinds of constraints there are around testing,” Spangler says.

In 2015, the partnership was recognized for exemplary achievement by the National Association for Professional Development Schools.