Savannah, Ga. – University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography scientist Aron Stubbins joined a team of researchers to determine how hydrothermal vents influence ocean carbon storage. The results of their study were recently published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

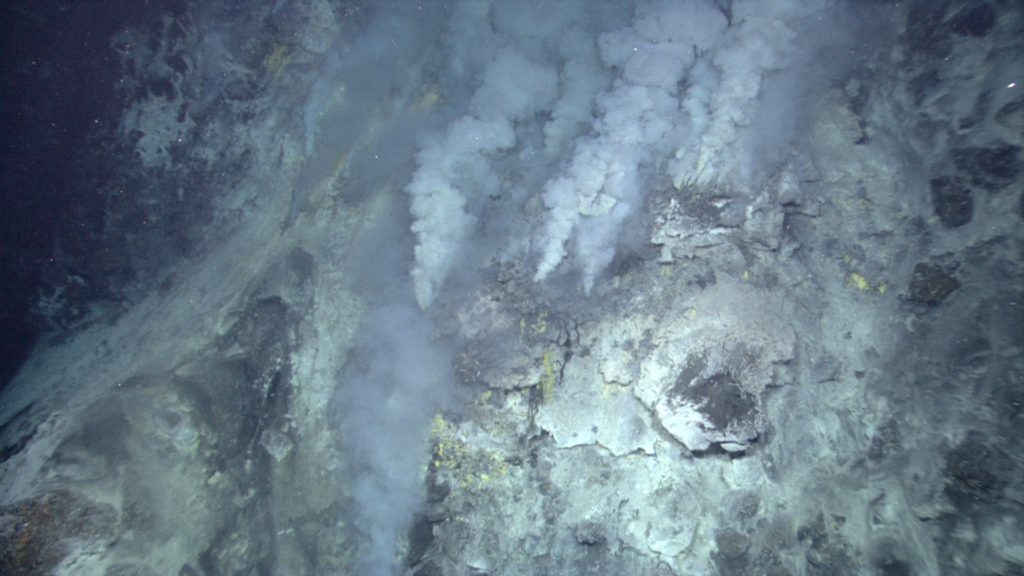

Hydrothermal vents are hotspots of activity on the otherwise dark, cold ocean floor. Since their discovery, scientists have been intrigued by these deep ocean ecosystems, studying their potential role in the evolution of life and their influence upon today’s ocean.

Stubbins and his colleagues were most interested in the way the vents’ extremely high temperatures and pressure affect dissolved organic carbon. Oceanic dissolved organic carbon is a massive carbon store that helps regulate the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere-and the global climate.

Originally, the researchers thought the vents might be a source of the dissolved organic carbon. Their research showed just the opposite.

Lead scientist Jeffrey Hawkes, currently a postdoctoral fellow at Uppsala University in Sweden, directed an experiment in which the researchers heated water in a laboratory to 380 degrees Celsius (716 degrees Fahrenheit) in a scientific pressure cooker to mimic the effect of ocean water passing through hydrothermal vents.

The results revealed that dissolved organic carbon is efficiently removed from ocean water when heated. The organic molecules are broken down and the carbon converted to carbon dioxide.

The entire ocean volume circulates through hydrothermal vents about every 40 million years. This is a very long time, much longer than the timeframes over which current climate change is occurring, Stubbins explained. It is also much longer than the average lifetime of dissolved organic molecules in the ocean, which generally circulate for thousands of years, not millions.

“However, there may be extreme survivor molecules that persist and store carbon in the oceans for millions of years,” Stubbins said. “Eventually, even these hardiest of survivor molecules will meet a fiery end as they circulate through vent systems.”

Hawkes conducted the work while at the Research Group for Marine Geochemistry, University of Oldenburg, Germany. The study’s co-authors also included Pamela Rossel and Thorsten Dittmar, University of Oldenburg; David Butterfield, University of Washington; Douglas Connelly and Eric Achterberg, University of Southampton, United Kingdom; Andrea Koschinsky, Jacobs University, Germany; Valerie Chavagnac, Université de Toulouse, France; and Christian Hansen and Wolfgang Bach, University of Bremen, Germany.

The study on “Efficient removal of recalcitrant deep-ocean dissolved organic matter during hydrothermal circulation” is available at www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v8/n11/full/ngeo2543.html.