A University of Georgia finance professor used the records of a Reconstruction-era bank to add fresh insights to the financial lives of newly emancipated African Americans, and how efforts to support them collapsed.

“What we found is this significant policy lesson about the importance of trust in encouraging financial participation,” said Malcolm Wardlaw, an assistant professor of finance at the Terry College of Business. “When you’re dealing with the trust and well-being of marginalized communities, you’re dealing with something fragile and whatever you do, you don’t want to harm it.”

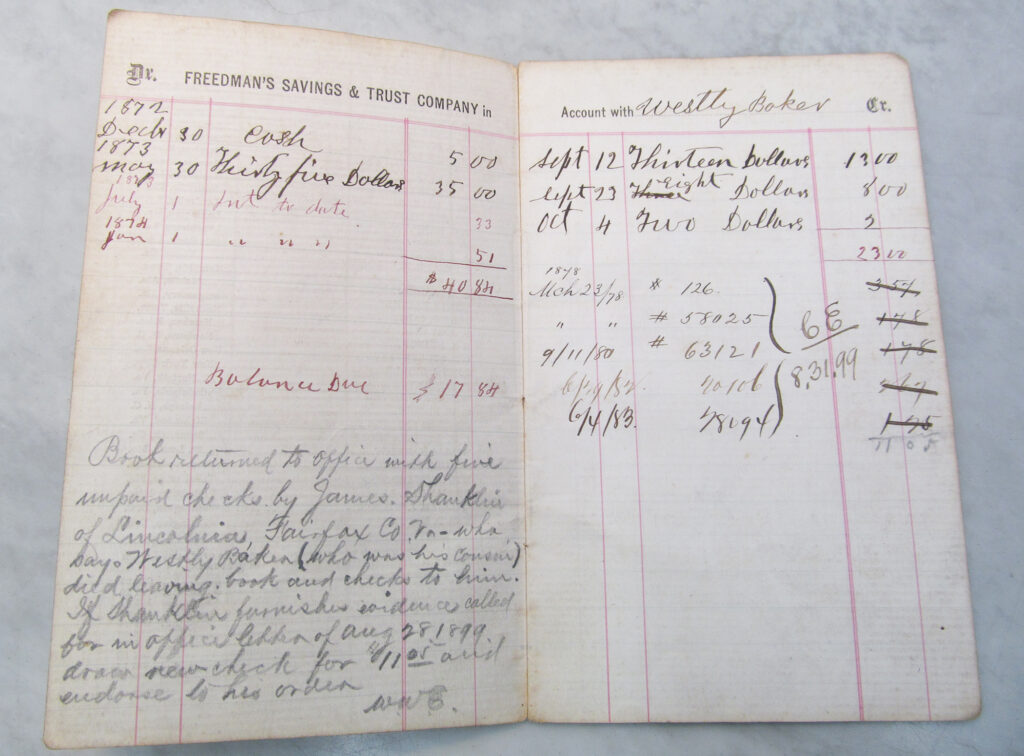

In 1865, the U.S. government established the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Co. in to help newly emancipated communities gain a financial footing. With 37 branches across the South and in New York, the bank initially flourished and grew to include more than 100,000 customers. But it collapsed in June 1874 after the Financial Panic of 1873.

Some of the Freedman’s Bank records have been lost to time, but many still exist. Wardlaw and his Ph.D. student, Virginia Traweek, found the archived records and decided to analyze the data to see what they could discover about African American communities after the Civil War.

The results were inspiring and infuriating, Wardlaw said. They’ve yet to publish their research in an academic journal but have posted their working paper, “Societal Trust and Financial Market Participation: Evidence from the Freedman’s Savings Bank,” and information about the public records they studied at freedmansbank.uga.edu.

The research project is the first to document the new bank depositors over time, describe the transaction behavior of depositors in response to outside events, like community violence, and examine and identify characteristics of depositors who escaped the bank’s failure or fell victim to it.

Records from bank branches in different cities — for example, Savannah, Birmingham and Atlanta — were merged and analyzed to see when people deposited money and who still had money in the bank when it collapsed.

One of the starkest findings was that deposits dropped precipitously whenever racial violence escalated in those cities, Wardlaw said.

“There were several events of racial violence that occurred, and it had a chilling effect on depositing behavior,” Wardlaw said. “Its impact was seen not just in the city itself but in the surrounding area. We characterized this as a shock to trust in institutions.”

The study also found that community leaders lost the most money when the bank collapsed, Wardlaw said.

Leading up to the bank’s 1874 collapse, many customers withdrew their savings, but many others in the African American community kept their accounts open. Business owners, pastors, teachers, churches and charities with strong local ties were left holding the bag, losing thousands of dollars when the bank collapsed.

“One of the things that you see is that older people who were from the area — people who were born and raised in the state — tended to be the ones who stuck around until the bank failed,” Wardlaw said.

The bank’s few white depositors were twice as likely to recoup their full deposits as African American depositors. Wardlaw suggested this may have been because white citizens had more experience with the banking system and could see the bank’s collapse coming.

What’s evident, however, is that the bank’s failure hurt African American confidence in financial institutions during Reconstruction, Wardlaw said.

“You have community leaders who are probably more important to the long-term stability of the bank, but they’re also the ones who are most likely to get hurt,” Wardlaw said. “Our public policies need to take that into consideration. These are the core members of the community that we absolutely do not want to harm, yet could end up hurting them for generations.”