Researchers at the University of Georgia have developed a way to monitor the spread of COVID-19 in Athens using wastewater.

By measuring concentrations of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in sewage samples collected from local county water treatment plants, the team can track how the outbreak is unfolding at a community level in real-time.

This type of wastewater epidemiology has been around for a long time, said Erin Lipp, a professor of environmental health science in UGA’s College of Public Health and principal investigator.

“Basically, you get a huge volume of information about a population based on what goes down the toilet, from illicit drugs, pharmaceuticals and pathogens or other microbes that they’re carrying,” she said.

Adapting to COVID-19

When evidence began to appear in early spring that infected individuals could shed the virus in their feces, Lipp and members of her lab quickly realized that they could apply a similar technique to monitor COVID-19 spread in Athens.

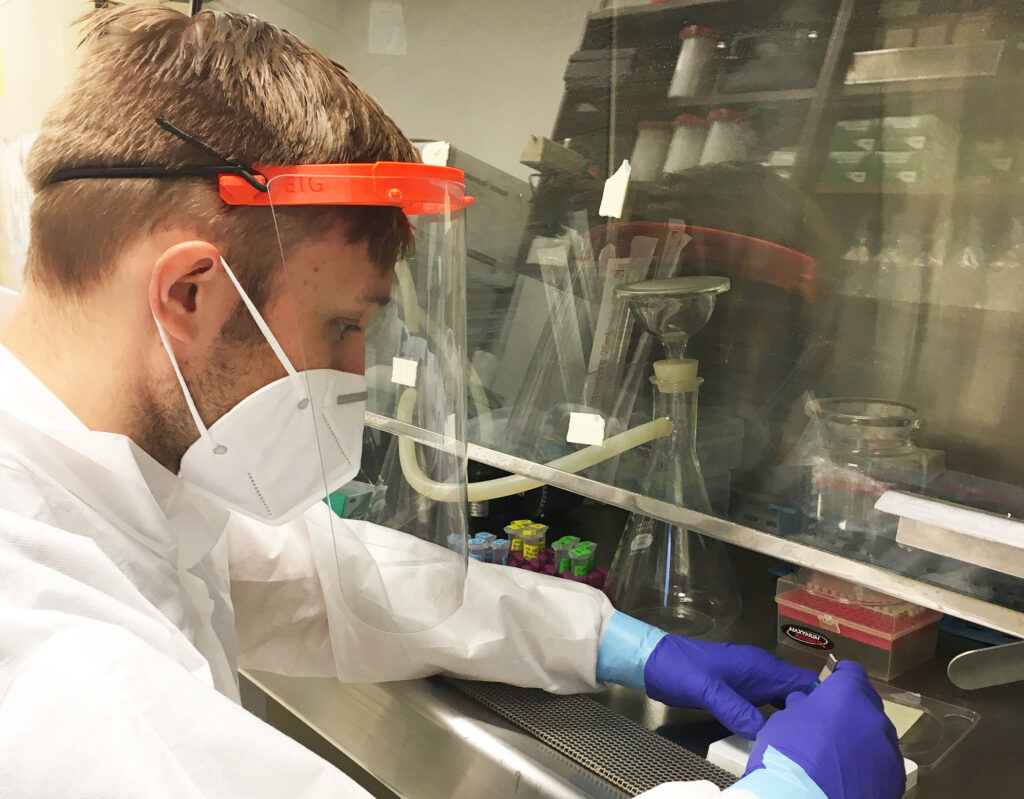

As project lead for the Lipp Lab, environmental health science doctoral student Megan Lott coordinates weekly sampling, analysis and communicating updates to collaborators.

“Our group has been working tirelessly for weeks to trouble-shoot and optimize methods to provide reliable results for our monitoring program,” said Lott.

Fellow lab member and doctoral student Megan Robertson helped to develop the methodology to extract SARS-CoV-2 virus RNA from filtered raw sewage samples, which took about a month to refine.

The team launched its weekly surveillance in early June, around the time when local and state stay-at-home orders were being lifted.

“We started seeing more cases in Athens in late June, and we were able to pick that up in our sewage signal,” said Lipp.

We can look very quickly at a whole community and get information in a much shorter period of time.” — Erin Lipp

This approach allows scientists to evaluate outbreak trends in real time, which for the purposes of early disease surveillance, is an advantage over diagnostic testing.

“Tests are taking 14 days in some cases to come back,” said Lipp. “We can look very quickly at a whole community and get information in a much shorter period of time.”

Recently, the Lipp Lab began publishing weekly data updates on the lab’s website.

“Eventually this will be published, but the real goal is to get this information out and hopefully to be useful to people,” said Lipp, particularly local leaders and decision makers.

Doctoral student and Lipp Lab member William Norfolk took the lead on visualizing the data for the website.

Informing the public

“I think it is every scientist’s hope that their research will benefit the greater community, and it has been an excellent experience to work on an evolving issue in real time to better inform the public and policymakers,” said Norfolk.

Lipp said the overall goal of this work is to understand the prevalence of COVID-19 in the community, but the project is still in early stages.

As methods improve, sample collection can be moved from a centralized wastewater plant into specific sewer sheds. This will allow researchers to understand if viral shedding “hot spots” exist in specific neighborhoods, industrial locations or areas of university and college campuses.

“There are still a lot of uncertainties – how many viruses a person sheds, how long they shed them for, [whether or not] everyone shed the virus in their feces,” she said. “Right now, it’s really going to be about trends. In the immediate, it’s understanding the dynamics of an outbreak.”

Weekly outbreak trends are available to the public on the Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases website. Data is updated each Thursday.