If a disease outbreak in a field could be considered a crime scene, then the “CSI” lab for such viral suspects is on the UGA Tifton campus, where samples collected from the scene are sent and tested. The culprits are always identified.

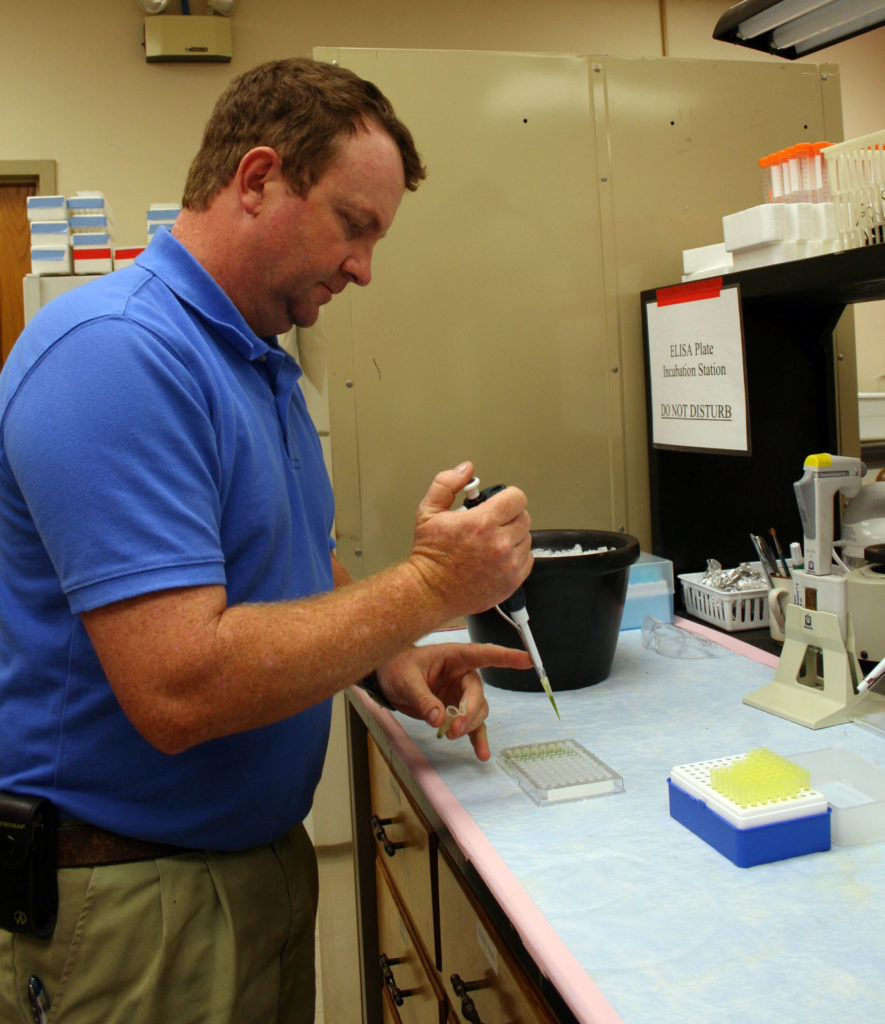

“Every crop we put in fields is susceptible to many viruses in Georgia,” said Stephen Mullis, a research professional with the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, who oversees the viral lab. “And what we do here in the lab is determine what virus is present and at what levels.”

Georgia’s environment is good for growing many crops. Unfortunately, that same weather is perfect for plant diseases, too.

Over the past decade, viruses have cost farmers hundreds of millions of dollars in damage or control measures. And no disease has caused more problems than the tomato spotted wilt virus, the disease that prompted the viral lab’s creation.

TSWV hit Georgia in the mid-1980s. By the 1990s, it was at epidemic levels, particularly on peanut and tobacco plants, according to Alex Csinos, a plant pathologist at the agricultural and environmental sciences college.

“Necessity is the mother of invention,” Csinos said. “We had a serious outbreak of tomato spotted wilt virus in the early ’90s. Since it was a new virus and no one else was doing any kind of work on that particular virus, we decided for us to save some of our crops from the destruction from this virus we needed to start our own laboratory on site to take care of the needs and requirements of the researchers who were studying the disease.”

The lab was established in Tifton, where samples could be efficiently handled in the heart of the state’s row-crop production area. Primary funding came from Phillip Morris International and the Georgia Tobacco Commission.

One sample is typically a leaf, stem or whole plant in a zip-close bag. Samples come from research plots, where scientists conduct tests to learn more about viruses and discover ways farmers can treat or prevent them.

“On a normal day, we run a few hundred samples,” Mullis said. “And in any given year we run 60,000 to 70,000 samples through this lab.”

The lab mostly serves the state’s tobacco industry, which has declined in recent years due to many farmers getting out of the business after the government dropped its Depression-era quota system. Farmers now contract their crops directly with tobacco companies, and profit margins are tight, according to Fred Wetherington, a tobacco farmer in Lowndes County near the Florida line. Staying ahead of diseases is a major and costly problem.

“For us, the lab in Tifton has been crucial,” said Wetherington, the chairman of the Georgia Tobacco Commission. “If it wasn’t for research, we’d be in a lot worse shape. Whether it is new varieties, new herbicides or nematocides, the research dollars up in Tifton have gone a long way for us.”

For the first time in a long time, Georgia’s tobacco harvest is good, Wetherington said. Weather was helpful and new strategies to control TSWV seem to be working across the state.

“We’ve got the best tobacco crop we’ve had in 12 or 13 years,” he said.

When not handling tobacco, the lab gets samples of other crops. Six years ago, it was on the forefront of discovering a mysterious virus threatening the Vidalia onion. Iris yellow spot virus caused major concerns then, but its damage has been minimal since.