Scientists know people’s genes can affect whether they become obese. But the flipside also appears to be true-being obese may affect the way a person’s genes function. UGA geneticist Richard Meagher thinks these changes may make obese people prone to other diseases.

When a person becomes obese, for example, fat cells start to produce high levels of hormones called adipokines. Too many adipokines can cause inflammation, which plays a role in cardiovascular disease and other obesity-related ailments.

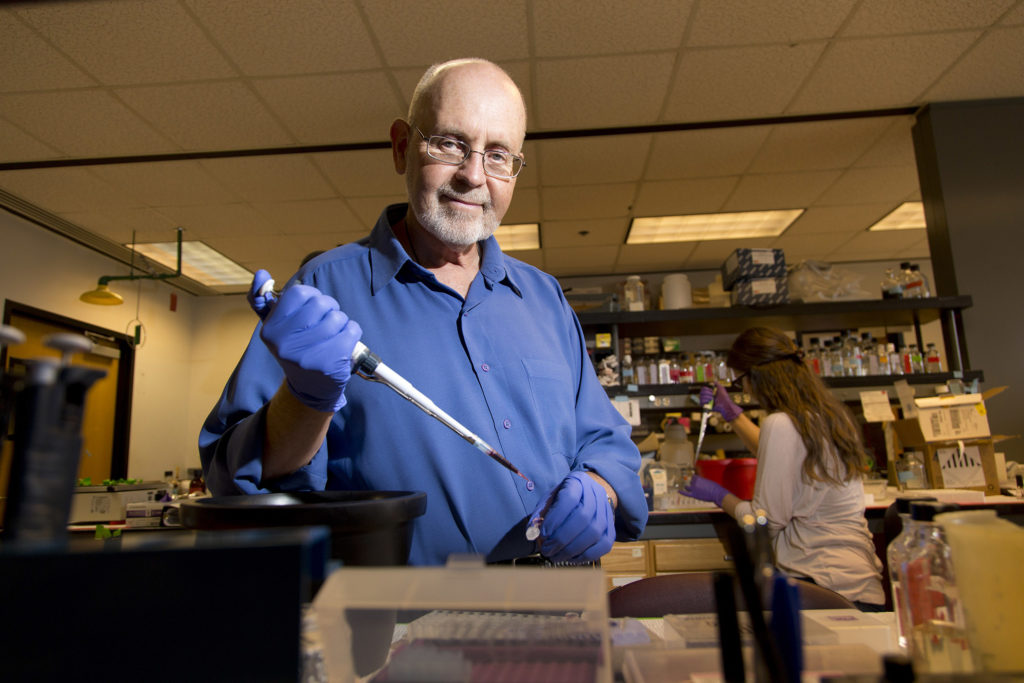

Meagher thinks the fat cells produce more adipokines because of changes affecting gene expression-the process by which the genetic information in a cell’s nucleus tells the cell what to do. He’s working on a way to study these alterations by creating special mice with glowing red tags on the nuclei of their fat cells.

Genetic information is stored in the nucleus as strands of DNA. Some changes, called gene mutations, affect the information itself. Other changes, like those Meagher is studying, affect whether this information is “expressed” or used by the cell. These modifications are called epigenetic changes.

“Epigenetic changes can reprogram these cells so they misbehave,” said Meagher, who is a Distinguished Research Professor in the genetics department of the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. “We’re trying to figure out how that’s happened.”

Unfortunately, it’s hard to work with fat cells, which are large and fragile. Instead, Meagher is developing a way to obtain the nuclei of the fat cells rather than individual fat cells themselves.

In the lab, Meagher and his colleagues are working to create mice with a fluorescent red marker on the nuclei of all of their fat cells. The fluorescent marker allows Meagher to easily collect all the fat cell nuclei in a sample of tissue containing other cell types. Then, he can study epigenetic changes to the DNA in these fat cell nuclei under different situations.

“We could change the amount of food and exercise the mouse gets and then see what happens to the epigenetics of its fat cells,” Meagher said.

Learning about how these conditions change gene expression could help scientists understand how obesity leads to other diseases.

“The other thing we’re hoping to do is to understand which obese people are going to be most susceptible to getting diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes or Alzheimer’s,” said Meagher, who is a member of UGA’s Obesity Initiative, a interdisciplinary effort to combat obesity in the state of Georgia.

Meagher presented his progress at Obesity Week 2013, an international obesity conference in Atlanta last fall. He and his collaborator, Clifton Baile, have been awarded a $430,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health for the project. A foods and nutrition and animal and dairy science professor, Baile also directs UGA’s Obesity Initiative.

So far, Meagher and his colleagues have created fat cells with the fluorescent marker and used it to collect the fat cells’ nuclei. They are currently in the process of creating mice with these specially tagged fat cells.

Meagher thinks that learning more about epigenetic changes might allow for the development of drugs that can counter the changes-and diseases or other negative effects they may cause.

If we understand how gene expression is changing, “then we can learn how to make it change in a desirable way,” Baile said.