Some people go through life as optimists. Others are pessimists. But, for Sun Joo “Grace” Ahn, an assistant professor of advertising at Grady College, she is a realist—a virtual realist. Virtual reality is becoming part of the everyday lexicon for many consumers, but it has been in Ahn’s everyday vocabulary for nearly 10 years.

“Twenty years ago we went through an Internet revolution,” Ahn said. “Ten years ago we went through the mobile revolution, and now we are right at the cusp of a virtual reality revolution because now the devices are getting cheap enough.”

Ahn credits the fact that major companies now are embracing virtual reality to simple economies of scale—as the price of virtual reality devices goes down, more people will carry them around.

“I expected virtual technology to be a future thing for a really long time, but now that major companies are jumping in to make these cheaper devices, it’s really picking up speed,” Ahn said. “If it gets cheap enough and there is enough content, then this will literally change the way we think about communication.”

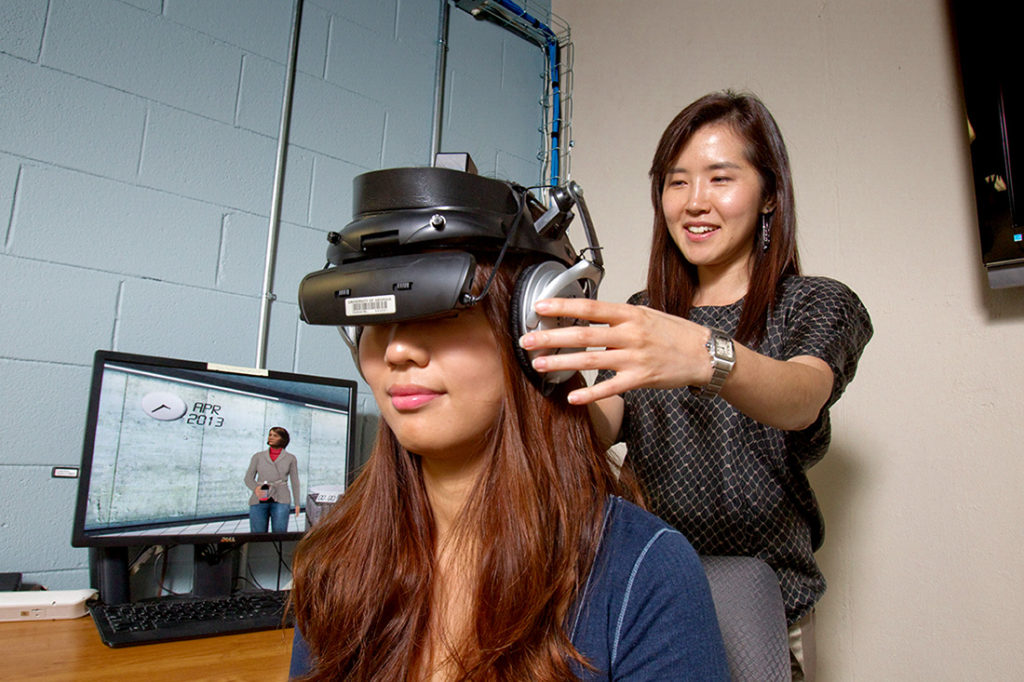

While a lot of current attention is paid to using virtual reality in gaming and entertainment, much of Ahn’s research is looking ahead to incorporating the technology into persuasive messages in health applications and seeing how to make them personally relevant to the subjects.

One such study is Ahn’s research proving there is a direct, positive effect between viewing a time-lapse, computer-generated video of someone gaining 10 pounds a year from drinking a soft drink and the reduction of sugary beverage consumption. Many people who smoke or drink sugary beverages know there is no eminent danger—they don’t feel like they are going to die tomorrow. Ahn studies how messages can be delivered to prove risk behaviors are more immediate, and one way of doing this is through virtual reality.

“People usually have a psychological distance with certain risk behaviors, and drinking sugary beverages is particularly distanced,” Ahn said. “People don’t think it’s a risk behavior because it seems like a harmless habit. If you can fast-forward time where the behavior and the consequence are brought together, the message becomes more salient and sticks with them longer.”

In another related study recently accepted in the Journal of Media Psychology, Ahn studied the effects of incorporating a virtual simulation message within a digital brochure.

Ahn found that people were much more likely to remember perceived risk using virtual simulation, especially when the health risks don’t seem very serious, for example, soda drinking.

“When incorporating the virtual simulation, the perception of risk is significantly higher, it lasts longer and people remember it more,” Ahn said. “And, personally they feel more involved with the issue, so essentially it’s getting people to consider it more personally relevant to them. Virtual reality really does change behavior; sometimes it’s the medium that matters.”

In another study published in Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, Ahn studied the effects of using virtual pets to encourage 7- to 13-year-olds to eat fruits and vegetables.

The children set goals for healthy food consumption, and they were able to watch their virtual pet become healthier when the children ate more fruits and vegetables. The research studied the consumption goals the children made after they interacted with the virtual pet and then measured intentions by what they put on their plate at meals, and their actual consumption. When the children ate a lot of fruits and vegetables, they were able to use a joystick to pump the heart of the dog, which would become easier when lots of healthy foods were consumed. They could also feel the virtual pet’s main artery, which was more elastic when fruits and vegetables were

consumed.

“In terms of actual consumption, kids in the virtual pet group ended up serving themselves a lot more fruits and vegetables than kids in the other two groups,” Ahn said. “Did they eat what they put on their plate? Virtual pets had a little more healthy consumption but not significantly different. Both intervention groups were significantly higher than the baseline group. They all had good intentions.”

Ahn also has worked with virtual pets to encourage physical activity in children. When the children reach a goal, they are rewarded by being able to teach their virtual pet a new trick. Studies printed in the Journal of Health Communication showed that the children in the group with a virtual pet engaged in 156 percent more physical activity than the control group.

Currently, Ahn is working with Kyle Johnsen in the College of Engineering, Georgia Tech and the Children’s Museum of Atlanta on a National Science Foundation funded project that pairs a virtual buddy with children viewing museum exhibits. The virtual buddies will reinforce the STEM education and learning through virtual peers.

“Studies show that when children model other people, they like to model peers, instead of adults,” Ahn said. “We expect the virtual buddies to work as a bridge between formal learning in the classrooms and informal learning in the museums. We want to make sure they come away knowing that the museum exhibit is teaching the same STEM concept they learned in the classroom.”

Consumers are just seeing the beginning of the virtual reality revolution, according to Ahn who cites the recent free distribution of Google Cardboard by The New York Times to its subscribers as a striking point in virtual reality history.

“It was a paradigm-changing experience for a lot of people to realize it was so cheap that people were passing it out,” Ahn said. “Google Cardboard doesn’t have full capabilities, but it gives the everyday consumer an idea of what the future could be like.”

For now, Ahn is continuing her frantic pace of research.

“As a scholar you always want to be doing the current stuff—the topics that are relevant to consumers,” she said. “It is always exciting to realize that what you have been doing for a while is finally getting some attention.”