After tornadoes touched down in the Southeast on April 27, 2011, many people in the storm’s path took to the Internet, posting images of the aftermath on Facebook.

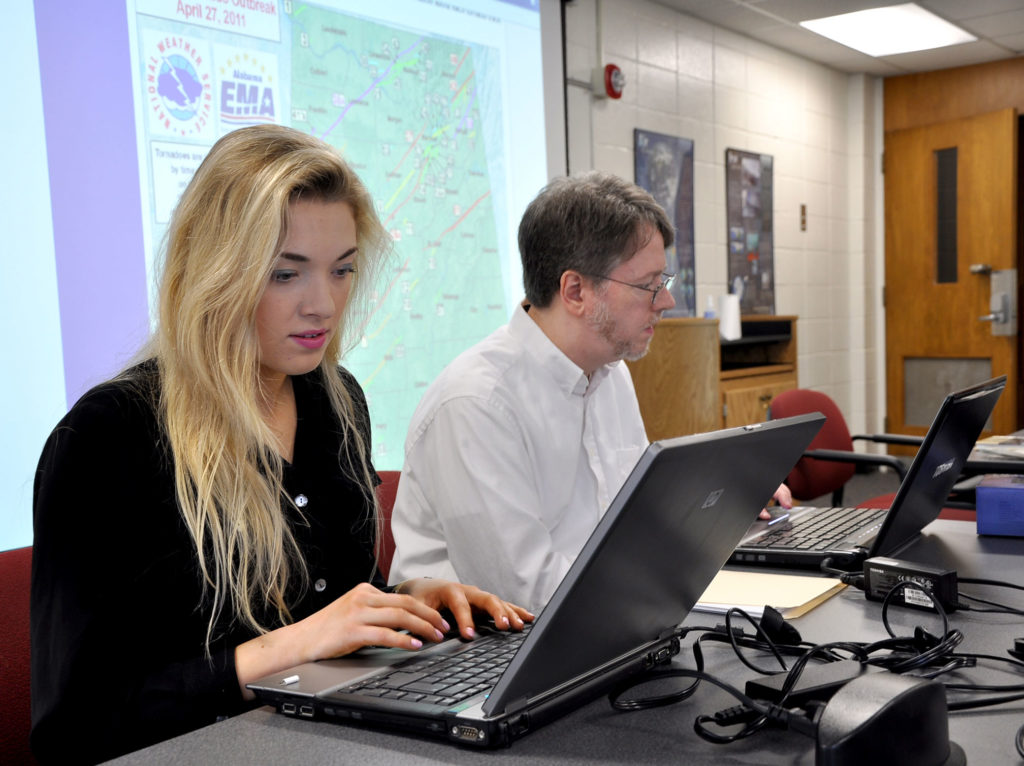

While those affected by the tornadoes’ impact were helpless to their power, John Knox, a faculty member in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, and his student researchers harnessed social media to learn more about the storms’ behavior. They used photos and information on Facebook to build and analyze a database of the debris, creating the most comprehensive study-to date-of debris trajectories from a tornado outbreak.

The results one day could aid public safety response to future tornadoes.

“Our study highlights the still mostly untapped potential of social media databases in scientific research,” said Knox, an associate professor in the geography department and a faculty member in the atmospheric sciences program.

The project started when Alabama resident Patty Bullion compiled a Facebook page on “Pictures and Documents found after the April 27, 2011 Tornadoes.” Using the images and information as a starting point, the UGA team compiled a scientific database and used mapping software and numerical trajectory modeling techniques to pinpoint the takeoff and landing points of 934 objects that were found and returned to their owners.

“Even 10 years ago, the items of debris left behind by a tornado outbreak-in our study, everything from metal signs to quilts and photographs-probably would have been thrown away, and that would have been the end of it,” Knox said. “But with the wide reach of Facebook, Patty Bullion was able to reunite owners with items they lost from their homes, especially family pictures that traveled hundreds of miles in some cases. And we, in turn, were able to use the information Patty gathered to analyze that information scientifically.”

The research team determined that objects traveled nearly 220 miles, exceeding the previous record for the longest documented trajectory of debris from a tornado.

The study recently was published online by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. The study co-authors were two graduate students-current doctoral student Alan Black and former doctoral student Vittorio Gensini, now an assistant professor at the College of DuPage in Illinois-and nine undergraduate students-Jared Rackley, Michael Butler, Corey Dunn, Taylor Gallo, Melyssa Hunter, Lauren Lindsey, Minh Phan, Robert Scroggs and Synne Brustad, who is now at the University of Oslo, Norway.

The researchers established that the farthest-traveling debris objects took a somewhat different path than the rest of the debris.

“The winds turn clockwise as you go up in a severe weather situation, with southerly winds at the surface and very strong westerly winds at the tops of thunderstorms,” Knox said. “Based on our analysis of the tornado debris data, we hypothesize that the longest-traveled objects went up the highest, where they encountered winds that blew the debris downwind and slightly to the right of the tornadoes’ paths.

“This could be of importance in the future if tornadoes loft toxic or radioactive debris,” he added. “In such cases, it’ll be critically important for public safety officials to know where the debris will go, and our study is the most comprehensive work to date documenting where debris traveled during a real-life tornado outbreak.”