Tuberculosis is the ninth leading cause of death worldwide, and though the World Health Organization has said the average global burden of disease is on the decline, some areas of the world continue to feel its impact.

Researchers at the University of Georgia have received a $2.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to understand the local epidemiology of TB in African urban settings and help these communities develop targeted interventions to reduce transmission.

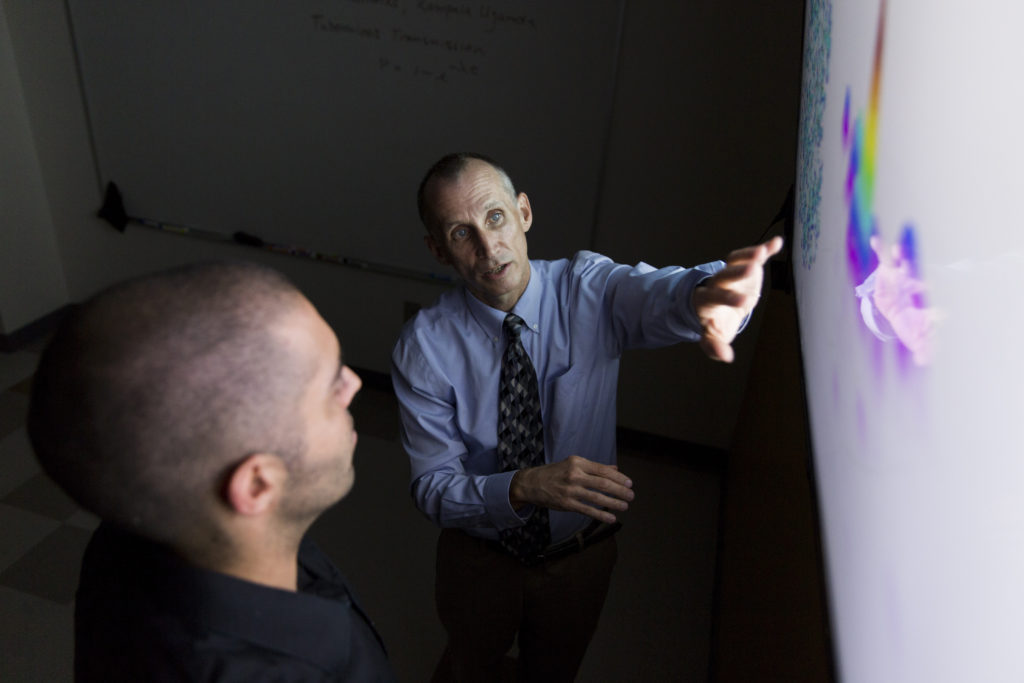

Led by physician and epidemiologist Christopher Whalen at UGA’s College of Public Health, the team will estimate where TB is being transmitted by combining information about patient movement with genetic information from the bacteria itself. Understanding where transmission is happening is the key to effective control, said Whalen.

The standard approach to tuberculosis control today relies on detection and treatment of tuberculosis disease, but this approach doesn’t work in areas where the disease burden is high.

“By the time a case is diagnosed and treated, the next generation of cases has already been newly infected,” he said.

Whalen has been working with colleagues in Makarere University in Kampala, Uganda, for years trying to discover better ways to limit TB transmission.

From 2012 to 2017, Whalen conducted a study to track how TB moves within communities, but his findings were perplexing. The infection didn’t seem to spread within known social networks. That begged the question, where is transmission occurring?

“Then it dawned on me,” said Whalen. “Everyone is carrying a cellphone. By using archived cellphone records, we would be able to map where TB cases move and measure how much time they spent in different places.”

Whalen’s team collected preliminary data using cellphone records from 15 TB patients, and they found that these patients tended to go to the same spots.

“There are hot spots, or places where TB patients spend a lot of time. With this information, you can target areas with the usual community control strategies, such as TB screening, active case finding, and education. If you collect this cellphone information going forward, you’ll be able to see if your control strategies worked,” explained Whalen.

The new project will expand Whalen’s previous work to include genomic information about the organisms that will reveal the order and timing of TB infection among the cases. When this information is combined with the mobility data, the team will be able map where transmission is occurring at different levels within Kampala.

Whalen hopes this approach will provide an actionable prevention tool for tuberculosis control programs in communities facing a high disease burden.