In an era of instant online news and social media, little attention is paid to the decline of community newspapers and the estimated 3,000 U.S. weeklies that closed in the last 20 years.

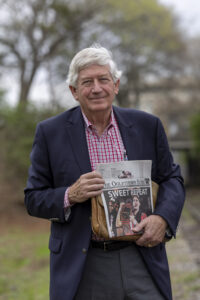

When Dink NeSmith ABJ ’70 heard that his friend Ralph Maxwell was shutting down his weekly newspaper, The Oglethorpe Echo, he was determined to prevent the nearly 150-year-old publication from being forgotten.

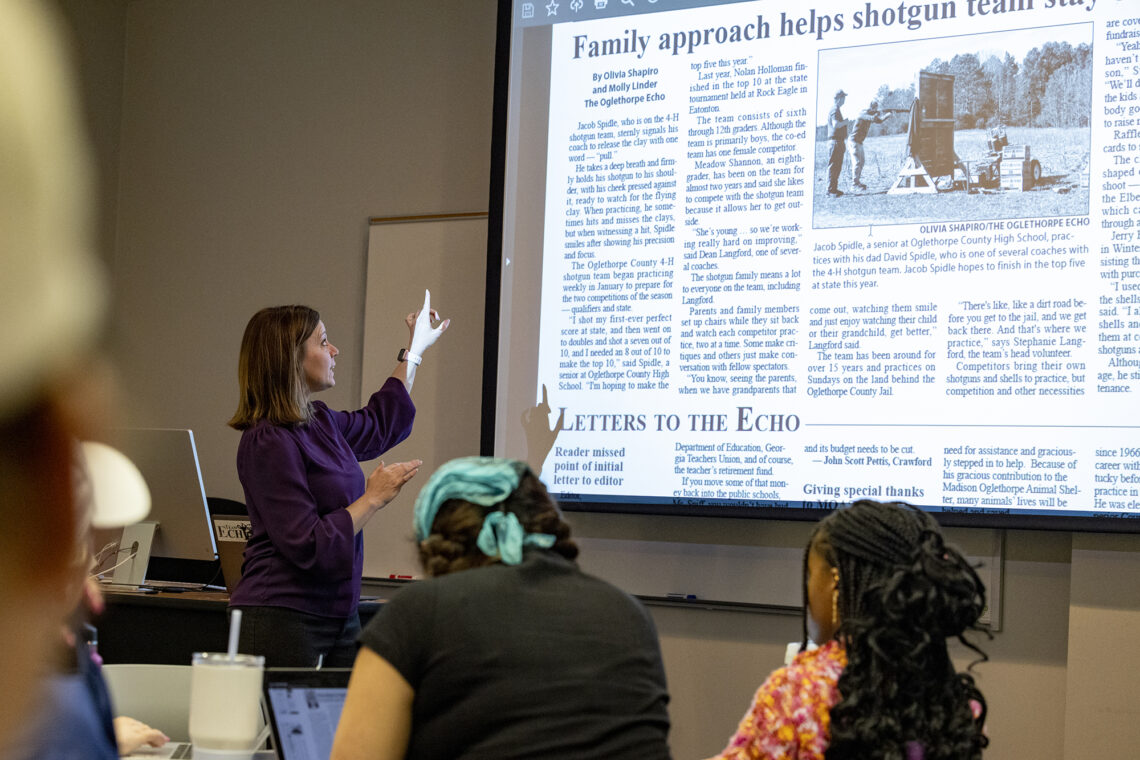

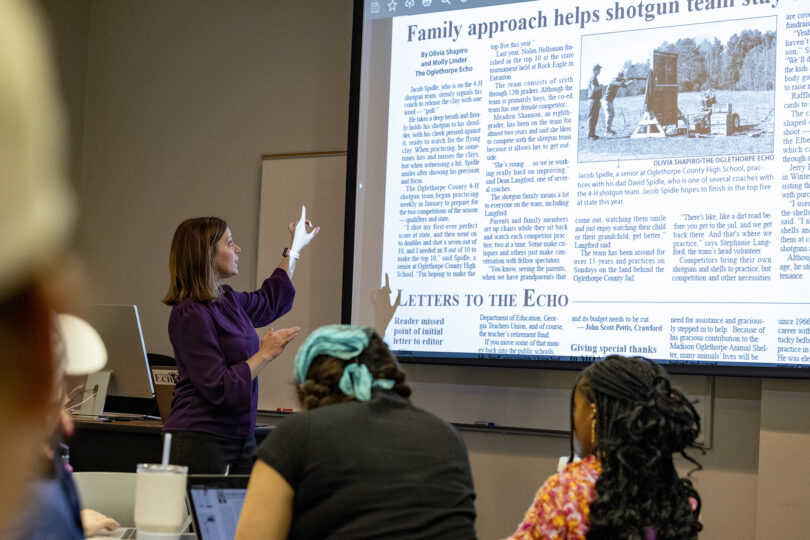

When longtime newspaperman and UGA alumnus Dink NeSmith learned that The Oglethorpe Echo would be closing down, he came up with the idea to save it using talent from the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication (Photo by Peter Frey/UGA)

Both NeSmith and Maxwell are long-time residents of Oglethorpe County, just east of Athens. They have known each other for almost 50 years. NeSmith is a co-owner of Athens-based Community Newspapers, Inc. (CNI), with publications in Georgia, Florida, and North Carolina. He has also been contributing a column to The Echo ever since he moved to Oglethorpe County a decade ago.

In 2021, Maxwell called NeSmith to let him know that due to health issues, he would be closing The Oglethorpe Echo. Though NeSmith understood, he couldn’t stop thinking about the history behind the local publication.

Maxwell’s father bought The Oglethorpe Echo in 1956 after retiring from the Navy, but the newspaper has been around since 1874. It’s a record of everything from local weddings to major changes in the legislature.

NeSmith remembers waking up at 6 a.m. after that phone call and realizing he needed to speak with Maxwell right away. He jumped into his pickup truck and drove to The Echo offices. NeSmith arrived just as Maxwell was finishing the story that announced the end of the newspaper. He immediately urged his friend to think of a new solution.

“Well, what are we going to do?” Maxwell asked him. “Are you going to buy the newspaper?”

NeSmith looked up at the ceiling, searching for an answer. Then, inspiration struck.

He would create a nonprofit and Maxwell would donate The Echo to it. All that was left was to hammer out the details. After leaving the office, NeSmith called Charles Davis, dean of the University of Georgia’s Henry W. Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

“I’ve got an idea,” NeSmith told him. “I want to turn The Oglethorpe Echo into a real-life experience for aspiring journalists at the Grady College.”

Davis loved the idea, and he and NeSmith built a sustainable business model for the future of The Oglethorpe Echo.

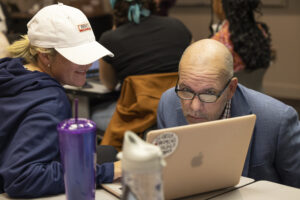

Grady faculty member Andy Johnston, seen here with fourth-year journalism student Olivia Shapiro, leads the capstone course and serves as The Echo’s editor. (Photo by Dorothy Kozlowski/UGA)

They developed a capstone course with The Echo as its foundation. Students experience a working newsroom which acts as a springboard into their careers.

At the same time, The Echo, which normally functioned with a single reporter, gained a revolving team of eager student journalists.

With NeSmith and Davis working together and the community supporting them, they built the program’s framework in less than two weeks. Of course, they needed someone to run the newspaper. But that was an easy decision.

Andy Johnston ABJ ’88, MA ’21 had been teaching at Grady for a month when Davis called him in for a meeting.

“Oh, no, what have I done already?” Johnston remembers thinking.

It was a pleasant surprise when Davis invited him to lead the new partnership between The Oglethorpe Echoand Grady College. As the adviser for The Red & Black from 2018 to 2020, Johnston was familiar with working with students and had an extensive journalism background.

Most importantly, he believed in the project.

“We’ve heard about other newspapers closing, especially in rural counties,” Johnston says. “When that happens, it means their only source of news and the only thing that holds people accountable is closing.”

Now Johnston joins the class weekly to review the week’s publication during their “postmortem.” They discuss what went right that week, what went wrong, and the students’ experiences reporting the stories.

He teams up with Amanda Bright, who teaches the course. Bright, a community journalist for her whole career at everything from midsize dailies to digital startups, helped create new digital platforms for The Echo, including an email

newsletter, four social channels, and an updated website.

“Audiences want to engage with different types of storytelling, and different types of stories need to be told on different platforms with different tools,” Bright says.

In addition to the student reporters and faculty leads, The Echo also runs on a team of 12 volunteers from Oglethorpe County that work at the main office. The reason The Oglethorpe Echo was able to continue its legacy is because everyone worked together—the students, Grady College, NeSmith, Maxwell, and the residents of Oglethorpe County.

“A good newspaper is a community talking to itself through its pages,” says NeSmith. “This newspaper is not only a recorder of history. It holds us all together.”

Fulfilling A Destiny

Destiny Hartwell is a journalism major with a double minor in sports management and communication studies, Hartwell also received a certificate in sports media from UGA.

Students in The Oglethorpe Echo capstone work in pairs on a variety of “beats,” or topics. Destiny Hartwell is on the cities and breaking news beat. (Photo by Dorothy Kozlowski/UGA)

Volleyball. Basketball. Shotput. Discus.

Calling Destiny Hartwell an athlete would be an understatement. But at UGA, Hartwell went from being the interviewee to the interviewer. She hopes to one day work for a major sports broadcasting network. Until then, she is polishing her skills at The Echo.

Students in The Oglethorpe Echo capstone work in pairs on a variety of “beats,” or topics. During reporting weeks, students in each beat do their own photo, video, and graphics work. Every other week, they serve in editor or producer roles for the whole publication. Hartwell is on the cities and breaking news beat.

“I didn’t expect people to allow me into their lives,” she says. “When I realized they were so welcoming, I was able to really dive in and find these cool stories.”

One of those stories was about Kendall Strickland, a Black entrepreneur who owns a fresh produce stand in Oglethorpe County. In a county that is predominantly white, Hartwell wanted to explore a Black-owned business and its place in the community.

Hartwell spoke to Strickland for several hours in multiple interviews, but she got the most out of their conversation while he worked at the stand, listening to him speak to customers.

The Rhode Less Traveled

Jack Rhodes is a double major in journalism and marketing, after graduation Rhodes will attend the School of Law.

Jack Rhodes deep dives into every story. There is always something to be done. (Photo by Dorothy Kozlowski/UGA)

Soil amendments.

It’s not a term that gets a lot of attention, but Jack Rhodes’ three-part series (so far) about the legal dumping of waste on private property has generated a lot of buzz. He’s reported on concerns from Oglethorpe citizens as well as the state legislature, and the headlines just keep coming.

This is a prime example of how solutions journalism works in small communities. Major news networks are flooded with stories focused on problems. However, solutions journalism, what Bright loosely describes as “rigorous reporting on the responses to problems,” highlights how communities react to an issue and what’s being done in response.

Everyone in The Oglethorpe Echo capstone writes a solutions journalism piece. In 2022, Grady College was named one of the nation’s first solutions journalism hubs.

“We go in, and it does not feel like class. When I’m headed there, I feel like I’m gearing up to go to work,” Rhodes says.

Unsinkable Molly

Molly Linder is a journalism major in the sports media program and is also completing the Double Dawgs program for her master’s in emerging media.

Molly Linder (left) learns how to line dance from instructor Debbie Winsett. It was one of the most memorable stories she has written for The Echo.

Molly Linder is from Dade County, a rural county in the northwest corner of the state with a population of just 16,000 people. She was drawn to The Oglethorpe Echo and its stories that seemed so familiar to the ones she grew up reading.

“Working for The Echo kind of feels like home,” says Linder, who is on the sports and recreation beat. “It’s very similar to my hometown. The people are super

welcoming, and I wanted to get that feeling of being at home but still exploring a different avenue.”

She recently completed a story about a line dancing teacher where she created a video package of the class and even learned a few moves herself.