Growing up, Nathaniel Patton wasn’t sure why his sisters got most of his parents’ attention.

“It was always like, ‘Oh, we can’t do that because Madeleine’s sick’ or ‘Valerie has an appointment,’” he says. “It was really confusing, and there was a little bit of resentment there.”

Patton MS ’20 didn’t know his sisters were sick. Really sick.

He spent most of his young life in hospitals, visiting them, attending doctor’s appointments with his sisters and his parents, and getting to know the health care system far better than any child should.

When his sisters passed and he grew up, Patton began to recognize how traumatic these experiences had been. And he also realized that he didn’t want other children to go through similar trauma alone.

Patton was working at Camp Twin Lakes, a nonprofit that offers year-round programs for children and families facing serious illnesses, disabilities, and life challenges, when he first heard about the University of Georgia’s child life graduate program.

Housed in the College of Family and Consumer Sciences (FACS), the program prepares students to fill a unique—but incredibly important—role in health care settings.

“There’s kind of a joke in child life that you don’t know it exists as a field until you’ve been forced into interacting with it,” Patton says. “And that’s usually not a fun introduction.”

What are Child Life Specialists?

Child life specialists “in both health care and community settings … help infants, children, youth, and families cope with the stress and uncertainty of acute and chronic illness, injury, trauma, disability, loss, and bereavement,” according to the Association of Child Life Professionals.

Child life specialists are there when things get hard, with the goal of making the process just a little bit easier on children and families who find themselves in hospitals, doctor’s offices, and sometimes even funeral homes.

For Patton, having someone like that explain what was going on with his sisters would’ve made all the difference.

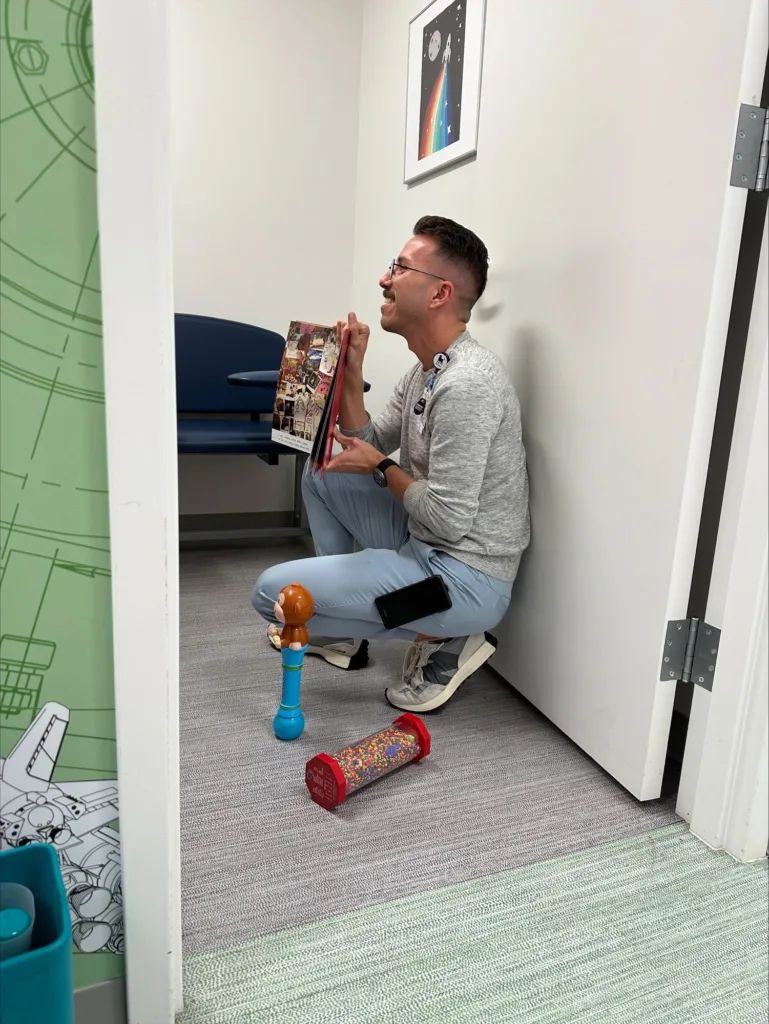

“One thing I always do is try to include siblings, especially when we have kids who are chronically ill or maybe can’t do things for themselves,” says Patton, who now works as a certified child life specialist at Inova Children’s Hospital in Fairfax, Virginia. “Asking if they want to help pick the color Band-Aid their sibling gets flips the whole script. They feel like they are part of this care team.”

Playing with Purpose

This year, FACS celebrates 30 years of its joint child life program with Augusta University.

In addition to earning a bachelor’s degree in human development and family science with an emphasis in child life, undergrads in the program also complete all the necessary coursework and clinical requirements to take the child life certification exam. And they spend 600 hours interning at Wellstar Children’s Hospital of Georgia in Augusta.

“What students are getting out of this partnership is almost full-time clinical experience,” says Diane Bales, director of the child life program at UGA. “They experience all different areas of the hospital, rotating under multiple child life specialists.”

Child life internships are extremely competitive, and this partnership gives UGA students a leg up by building experiential learning into the course requirements.

Bales also leads the master’s program in child life, which includes a 100-hour practicum, shadowing child life specialists in the field at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and several other facilities.

Although she fell into the specialty by accident, filling a void when the previous child life program director at UGA retired, Bales already knew its value.

When Bales was 3, she was hospitalized with a ruptured appendix.

“There was a nice lady who brought me toys and took me down to the playroom,” Bales remembers. “I was in one of the hospitals that originated child life, and I suspect that she was an early child life specialist that I had.”

But it’s not all toys, games, and play time.

“My education is in play theory, family systems theory, grief and loss theory, and child development,” says Sydney Beene MS ’22, who graduated from the program and now works as a certified child life specialist at Duke University Health System. “I combine all of those with a major understanding of the nuances of hospitalization to be able to support kids and families through some of the hardest days of their lives.”

A Hand to Hold. A Neck to Hug.

Child life specialists enter a heavy but incredibly rewarding field.

“I have potential students who come to me and say, ‘I just love kids, and I love playing with kids. I think I should be a child life specialist,’” Bales says. “One of my jobs is saying, ‘That’s great. But are you prepared to have a child throw up on you? Are you prepared to sit next to a child who’s had their arm amputated in an accident and get them through that while the doctors examine them? Are you prepared to sit and hold a child’s hand when they die?’”

For some like Patton, that answer was yes.

During his time in the emergency department at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Patton and one other child life specialist responded to every single death in the hospital after 5 p.m.

They offered grieving families hand molds or prints, locks of hair, and recordings of the last heartbeats of their deceased loved ones.

Patton lost count of the number of bear hugs he’s been wrapped into, often followed by a family member saying, “We don’t know how to do this.”

And that’s where it comes full circle for Patton.

“Having lost my sisters and not having that kind of support, we were lost,” he says. “There is no playbook on grieving and loss, but being able to provide that support, that guidance, it’s an honor.

“I remember every face. I remember every single name.”

One little girl in particular stands out.

She has a rare genetic disorder, and the prognosis isn’t good. Her parents were scared. So was she.

During Patton’s first meeting with the family, the girl silently hid behind mom and dad and understandably freaked out when the doctors needed to draw blood.

“She wanted absolutely nothing to do with me,” Patton remembers. “I was like, ‘That’s totally fine.’ We validate that choice.”

When she came back the next week for more tests, Patton tried again.

No dice.

But slowly, as she returned every week, she started opening up. “Yes, we can color together.” “Yes, we can play and watch Bluey together.”

“There’s kind of a joke in child life that you don’t know it exists as a field until you’ve been forced into interacting with it, and that’s usually not a fun introduction.”

Nathaniel Patton,

Certified child life specialist,

Inova Children’s Hospital, Fairfax, Virginia

“Then one day she came in, and she jumped into my arms,” Patton says. “It was just that light bulb moment. Mom told me, ‘She couldn’t wait to come back, and she wanted to pick the pink Play-Doh.’”

The little girl finally felt safe.

“When that little girl comes into the hospital, she even says it. ‘I’m safe here.’”

And she is. Her condition is improving too. She’s getting better.

The little girl is 5 now, and Patton still sees her as the hospital staff manages her condition. She’s gone from weekly infusions to monthly ones.

They don’t watch Bluey anymore, though. And they no longer use numbing spray before her blood draws. Now, the two just chit chat.

This story appears in the Fall 2025 issue of Georgia Magazine.