Competition can bring out people’s best efforts. It’s true on the playing field, in the marketplace, and even in the classroom. UGA lecturer Leah Carmichael taps into her students’ competitive nature with impressive results every week in her undergraduate international law course in the School of Public and International Affairs.

Every Friday, the course holds a moot court in which two groups of students argue cases before a panel of student justices. Each case touches on a facet of international law, such as whether the U.S. is legally bound to afford a suspected terrorist, detained at Guantanamo, certain legal rights.

The students are all in. They arrive early to huddle with their teams and talk through strategy one last time.

The competition serves a purpose. Sure, it’s fun and gets the students invested, but that’s not exactly the point. Nor is it simply to learn the finer points of international affairs. The goal is to help the students develop critical thinking skills and knowledge they can apply for the rest of their lives.

Kellsie Davis, a third-year international affairs student with designs on becoming an attorney, says, “I feel like I’m actually developing skills that I will need one day instead of just regurgitating information onto an exam.”

What skills? They practice how to present an argument, consider a conflict from multiple points of view, and learn through experience (although simulated) the importance of the letter of the law.

Where is the instructor in all of this? Carmichael MA ’09, PhD ’14, a lecturer in the School of Public and International Affairs, facilitates. She probes each team’s strategies, makes suggestions on how to present, and encourages effective collaboration. But, mostly, she creates an environment where students can take charge of what they learn.

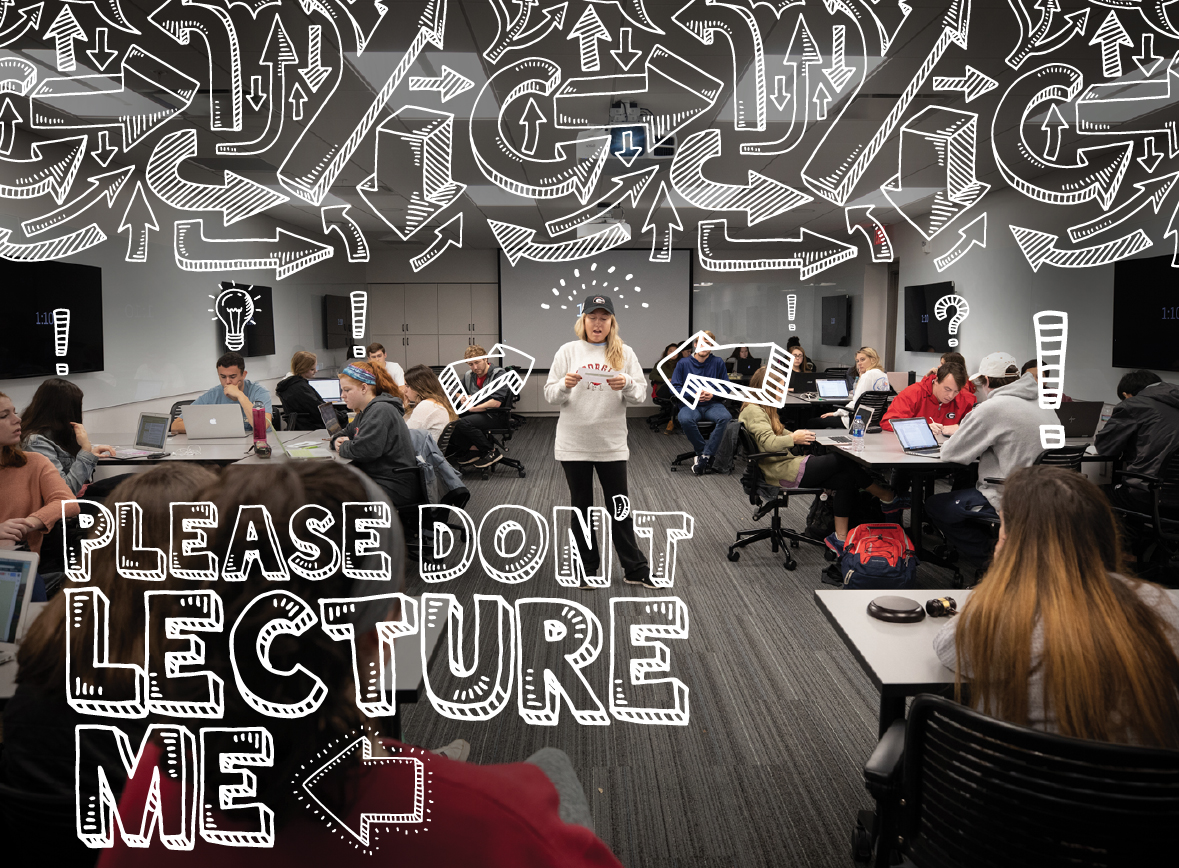

This is “active learning,” a teaching philosophy that pulls instructors out from behind a podium and fully engages them with their students.

Megan Mittelstadt, director of UGA’s Center for Teaching and Learning, describes active learning as a “two-way information exchange.” Instructors aren’t just transmitting information to students; they’re looking for feedback from students to gauge their understanding of the material. Instructors adapt their courses—sometimes on the fly—based on what students already know or think they know.

The evidence that active learning boosts student performance stretches back decades. Studies have found students are less likely to fail in an active learning environment than in a traditional lecture-based course, and they do better on assessments. Plus, the strategy has been effective across all disciplines—from physics and chemistry to business and political science.

In 2018, President Jere W. Morehead JD ’80 launched the Active Learning Initiative to invest $250,000 in training faculty and $1 million in transforming traditional classrooms into active learning environments across campus. The focus on active learning works in tandem with other initiatives (such as those focused on experiential learning, writing skills, and data literacy) to elevate an already exceptional undergraduate learning environment at UGA. The aim of all these initiatives is to prepare students to be successful in a rapidly changing global economy.

Carmichael was one of 32 faculty in last year’s Active Learning Summer Institute, a six-week deep dive into transforming courses with active learning. The institute helped her refocus what she wanted students to learn from her course. “It reminded me to actually think about these students and the skills they will need 10 years from now,” she says.

This new active learning pedagogy, either learned or adopted from the summer institute, impacted approximately 8,400 students in fall 2018 and spring 2019 courses. The Center for Teaching and Learning will begin to assess learning outcomes later this spring to determine the real impact active learning has on UGA students in these courses.

“Preliminary data based on improved test scores suggest that students have learned more than in the previous traditional learning environment in those same courses,” Mittelstadt says. “We project the impact to be much deeper as students progress through college and apply their knowledge to their other courses.”

In practice, active learning takes many different forms, and an in-class competition is only one tool in the active learning chest. For example, role-playing games have limited utility for assistant professor Tarkesh Singh’s 75-seat biomechanics course in the College of Education’s Department of Kinesiology. The class, which explores how the intricate laws of mechanics affect human movement, is intended for future clinicians: doctors, physical therapists, and athletic trainers.

For students to understand the complexity of how Newton’s laws of motion apply to, let’s say, a tightrope walker, Singh has to stand in front of the class and explain concepts of balance and rotational dynamics. But he uses group discussions and mobile technology to keep up the two-way flow of information. Students submit individual answers to in-class math problems from their phones or laptops. From there, Singh can figure out what percentage of his class is getting the right answer. If most are correct, he moves on. Otherwise, he refocuses on helping students understand the concept.

“He explains something, lets us process it with classmates, and asks practice questions. That solidifies it in your brain,” says Sarah Williamson BSEd ’18, an aspiring doctor who took Singh’s course in the fall.

Williamson says what she really took away from the class, beyond just facts and formulas, is how to think through problems and come up with solutions. That’s exactly the skillset that faculty are trying to instill in tomorrow’s doctors, attorneys, and the rest of the future leaders who are shaped at the University of Georgia.

Classroom Renovation

As UGA faculty continue to adapt their teaching strategies to help students prepare for a rapidly evolving economy, the university is making sure the physical classrooms are conducive to active learning environments. This means redesigning rooms and lecture halls to promote group work and pull the instructor into the students’ learning space.

New classrooms are being constructed with active learning in mind. And the university is invested in retrofitting older classrooms—many built with rigid chairs directed to the front of the classroom—into active learning spaces with rotating or movable chairs and interactive technology.

Park Hall, an iconic rite-of-passage building for the majority of first-year students taking core English and foreign language courses, is one of six buildings undergoing this transformation. Chairs bolted to the floor and old-fashioned chalkboards are being replaced with movable desks and chairs facing newly installed white boards and computer-operated overhead projectors. The rooms will be reconfigured to transform instruction to more actively engage students in the learning process. Nine classrooms across campus, including those in Park, Aderhold, Boyd, and Caldwell Halls, as well as the Geography Building and the Miller Learning Center, are undergoing a major redesign that will be completed next summer.