During a game of tennis with a friend, Tarkesh Singh experienced first-hand the very incident he hopes to make a difference in with his research—an accidental fall by an individual with Parkinson’s disease.

After bouncing the ball to his friend several times, a serve that landed further away caused him to lose his balance and fall over. To this day, Singh often plays the incident over in his head, evaluating and assessing it from the perspective of a sensorimotor neuroscientist.

After bouncing the ball to his friend several times, a serve that landed further away caused him to lose his balance and fall over. To this day, Singh often plays the incident over in his head, evaluating and assessing it from the perspective of a sensorimotor neuroscientist.

“He was following the ball with his eyes, but could not make a decision in time to move one way or the other, and then he fell,” said Singh, an assistant professor in the College of Education’s kinesiology department. “I feel like this is a big reason why we need to better understand deficits in eye movements in people with Parkinson’s disease and how it relates to deficits in their limb movements.”

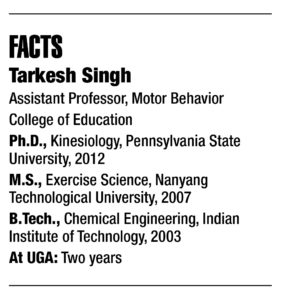

Singh, who serves as the director of UGA’s Sensorimotor Neuroscience Lab, is fascinated with movement and has studied movement control in a range of populations, from young children carrying heavy backpack loads to older individuals affected by stroke and Parkinson’s disease. After receiving his master’s degree in Singapore, Singh shifted his focus from athletic performance and gait stability to stroke rehabilitation. Since joining UGA’s faculty in 2017, his research has primarily focused on how hand-eye coordination and movement are impacted by Parkinson’s disease.

“I think of movement as the only way we can interact with the real world,” he said. “And I was always very fascinated with how people from different cultures interact with the world around them. And so, movement came as a very fundamental way of looking at the world, and I think that has shaped my perspective on research and science.”

For the past two years, Singh—who currently teaches an undergraduate course on biomechanics and a graduate course on motor control—has been creating a trifecta partnership between businesses, clinics and the Athens community to serve as a clinical model for researchers at the university. He formed a partnership with Athens Neurological Association with exercise science professor Kevin McCully, and is also working with Keppner Boxing, a local fitness center in Clarke County.

With the help of these partners and a team of 10 students at both the undergraduate and graduate level, Singh is investigating whether non-contact boxing can alleviate the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, which include slowed movement, impaired posture, rigid muscles and tremors. He plans to train half of his participants with non-contact boxing and half with an aerobic exercise intervention and compare the effects using a combination of methods, such as robotics, eye-tracking, surface electromyography, magnetic resonance imaging and more to measure minute changes in eye movement and muscle activity.

While previous researchers have looked at the effects of boxing on Parkinson’s disease, results from these studies were measured by physical therapists. Singh and his students are approaching their work as neuro-behavioral scientists and are using equipment to measure movement and eye changes up to an accuracy of 5 millimeters and 5 milliseconds—improvements that may reveal how subtle changes in behavior occur in the early stages of the disease.

“The science now is far more interdisciplinary than it was 15 or 20 years ago,” said Singh. “The challenges we take on involve a lot of programming and complex machine learning techniques. For students, it’s good because they get to learn from each other, they get to see different aspects of research. This is the future—we have to bring together people from very diverse training backgrounds to solve complex problems.”