Climate is likely the biggest driver of butterfly abundance change, according to a new study by University of Georgia entomologists.

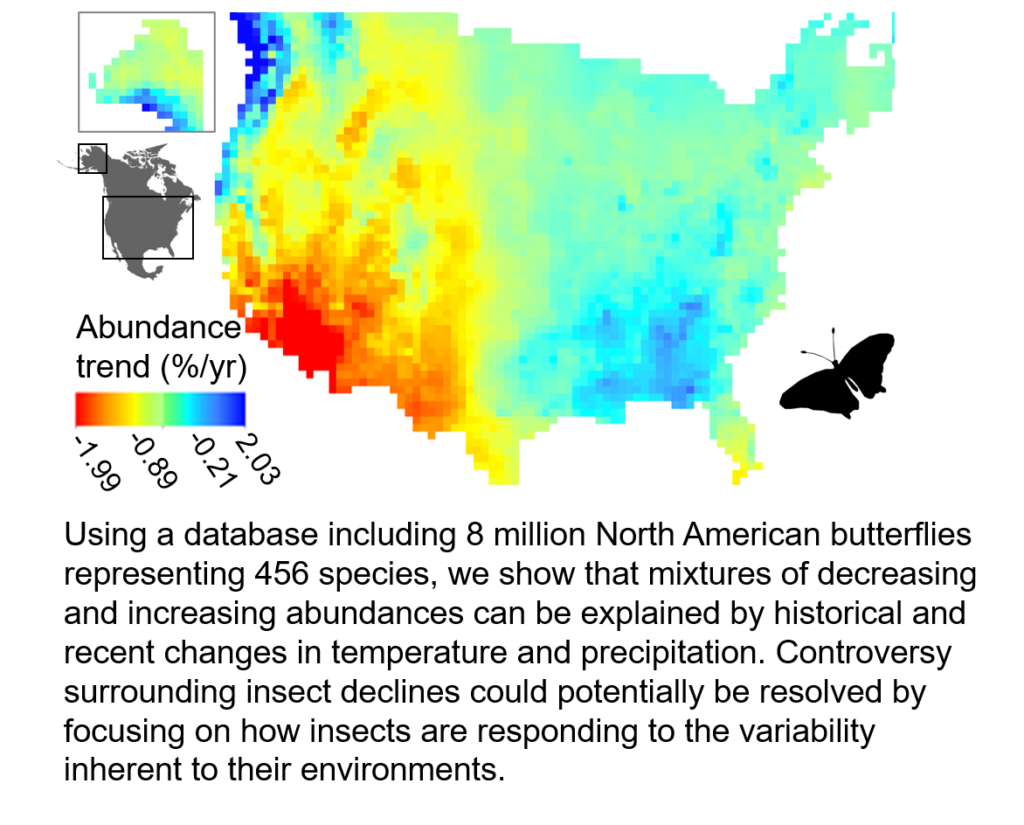

Researchers in the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences found notable increases in butterfly populations centered around the southeastern and Pacific Northwest parts of the United States, while the southwestern and Mountain States show a decline, a finding consistent with another recent studyfocused on western butterfly trends.

The team of scientists examined abundance and biodiversity trends for North American butterflies over a period of 25 years using a unique citizen-science dataset that has recorded observations of over 8 million butterflies across 456 species, 503 sites and nine ecoregions. They compared this with precipitation, temperature, and urban and agricultural land use.

Butterflies are ecologically important because they are pollinators, herbivores and prey, making them useful indicators of changes in the environment.

“They have a really important role,” said entomology professor Bill Snyder, who tracks ecological and species trends and has been following reports of insect declines in recent years.

“The whole idea of the ‘insect apocalypse’ is interesting to talk about, but there’s a whole lot of complexity. It really is region-specific,” he said.

Overall, the data showed a very slight decline of less than 1% per year. However, drops in two invasive butterflies, the Essex skipper and small cabbage white, disproportionately contributed to overall abundance declines. The mix of butterfly populations showed decreasing, stable or increasing populations depending on location and species.

Michael Crossley, a postdoctoral researcher in the department and lead author of the paper, sought to uncover the drivers of the changes. “There are all sorts of human-caused issues, and we sought to determine which might be causing the increases and decreases,” he said.

The whole idea of the ‘insect apocalypse’ is interesting to talk about, but there’s a whole lot of complexity. It really is region-specific.” — Bill Snyder

Average precipitation and temperature during the sampling period appeared to be the strongest drivers of this complex mosaic of abundance responses. Butterflies that are increasing in abundance might be benefiting from locally improved food resources or reduced stress in areas that have become wetter, according to the study.

“Even this complex mosaic in the changes of butterflies doesn’t mean it’s unpredictable. In this case, we’re finding this single driver. Where places that are hotter and drier there are decreases, and increases in places that are wetter and cooler,” Crossley said.

The data used in the study was compiled by the North American Butterfly Association from citizen-scientist monitoring effort over the past 26 years. Counts are made within a 15-mile area during the summer and are open to participation from the public.

“There’s only so many entomologists in the world, and having citizen scientists going out doing these counts has provided a totally unique data set that people have never done,” Snyder said.

Even so, the data still has some limitations.

The analysis reaches back only to 1993. “We can’t say anything about what happened before then,” Crossley said. “For example, extensive clearing of land for agriculture had already happened a century or more ago, and our study is blind to these historical changes.”

In addition, only sites from the contiguous 48 U.S. states, southern Canada and Alaska were analyzed, limiting the ability to predict changes in some regions, notably Mexico and northern Canada. “Even though it’s an amazing data set, there’s not a lot of data in Canada — so if species are moving north, we wouldn’t be able to see it in the data set,” Snyder said.

He plans to continue tracking butterflies and looking at what direction they’re moving. But the future of butterflies will likely depend on climate conditions, he says.

The study is published along with co-authors at Hendrix College and Rice University in Global Change Biology. Partial funding for the research came from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.