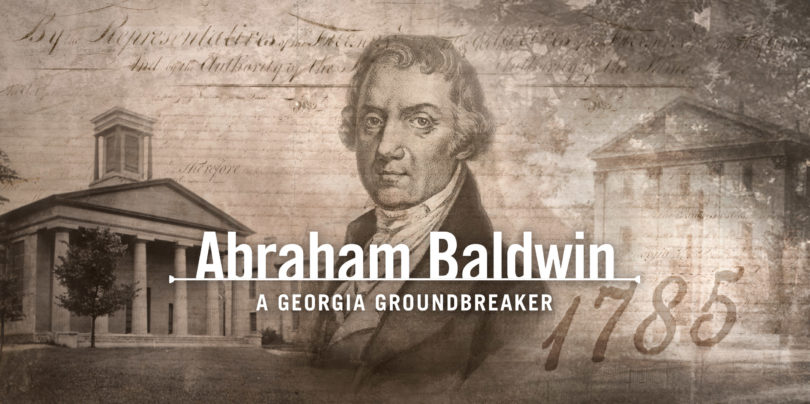

This is part of a series, called Georgia Groundbreakers, that celebrates innovative and visionary faculty, students, alumni and leaders throughout the history of the University of Georgia — and their profound, enduring impact on our state, our nation and the world.

If our newly formed nation had to pick a Founding Father to transform higher education across America, Abraham Baldwin would have been an unlikely choice.

The son of a Connecticut blacksmith, Baldwin was only 30 years old when he crafted one of the most revolutionary documents in our nation’s early history — the 1785 charter that established the University of Georgia as the birthplace of public higher education in America.

“Our present happiness joined to pleasing prospects should conspire to make us feel ourselves under the strongest obligation to form the youth, the rising hope of our Land,” Baldwin wrote in UGA’s charter, which was adopted by the Georgia General Assembly on Jan. 27, 1785.

“Our present happiness joined to pleasing prospects should conspire to make us feel ourselves under the strongest obligation to form the youth, the rising hope of our Land,” Baldwin wrote in UGA’s charter, which was adopted by the Georgia General Assembly on Jan. 27, 1785.

Two years later, as a Georgia delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787, Baldwin cast the crucial vote that saved the convention — and our nation — when both were in danger of dissolving.

“The University of Georgia and the U.S. Constitution are now in their third centuries, and we can’t overestimate how important both of them are, not only to the people of the state or the people of the country, but to the people of the world,” said Stan Deaton, a two-time University of Georgia graduate and senior historian at the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah.

“Abraham Baldwin was present at the creation of both, and I think the people of this nation and the world owe him a tremendous debt … because republics won’t work if citizens are not educated,” Deaton added.

Led by Baldwin, the establishment of UGA sparked a movement that continues to shape the nation — creating tens of millions of informed citizens, scientists and innovative entrepreneurs every generation.

Today, public colleges and universities across the United States educate 15 million students each year. This includes the more than 300,000 students throughout the public colleges and universities that make up the University System of Georgia.

A major public impact

According to data provided by the American Association of State Colleges and Universities:

- More than 70 percent of all college and university students across the nation — and more than two-thirds of all first-generation students — attend public institutions.

- More than half of all the bachelor’s degrees conferred in this country in engineering, the biological and physical sciences, math and agriculture are awarded by public institutions.

- Public institutions conduct 66 percent of all university-based research.

- The median earnings of college graduates with a bachelor’s degree are 67 percent higher than workers who only completed high school.

“In a global economy that requires both an educated citizenry and a robust national research enterprise, public higher education is not a luxury; it is the foundation of our competitiveness,” according to the Lincoln Project, a bipartisan advocacy group of educators, business executives and political leaders.

And it all started here

Because the University of Georgia was the first college supported by a state government, getting the charter right was important. There were no useful models; the nation’s few existing colleges, which had strong religious affiliations, were all private.

Baldwin’s background gave him the wide range of skills necessary to meet the challenge.

Although he graduated from Yale, an elite private college, Baldwin was from a middle-class family.

A theologian and Christian preacher who served as a chaplain in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, Baldwin was also a licensed lawyer who crafted language that specifically forbade religious tests for students wishing to enroll at the university.

It’s unclear why Baldwin decided to move to Georgia. One motivation may have been a plea from Georgia’s governor, Lyman Hall, a fellow Yale alumnus.

Baldwin, who had declined to take a Yale faculty position, knew that Georgia’s new college needed a broad intellectual capacity that also could support agriculture and commerce. He gave the people of Georgia the framework for a successful university that could serve future generations while fulfilling the expanding needs of a growing state.

The adoption of the University of Georgia’s charter was soon followed by North Carolina, which approved its charter in 1789 and opened its doors for students in 1795. This allows both states to claim “firsts” — the University of Georgia as the nation’s birthplace of public higher education, and the University of North Carolina as the nation’s first public college to admit students.

Learn more about the outstanding UGA men and women in the Georgia Groundbreakers series.

Two years after founding the University of Georgia, Baldwin played an instrumental role in another important milestone — the adoption of the U.S. Constitution.

Abraham Baldwin’s personal copy of a draft of the U.S. Constitution. (Courtesy of the Georgia Historical Society)

A compromise

When Baldwin arrived as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in June 1787, the convention was bitterly divided over how to structure the federal government’s legislative branch.

Larger states wanted to base representation on population, which would give them more clout. Smaller states favored equal representation for each state.

The dispute dragged on for weeks. Delegates feared the convention would collapse without a finished document.

“The fate of America was suspended by a hair,” Pennsylvania delegate Gouverneur Morris observed years later.

The crucial vote occurred on July 2, 1787. Baldwin, who initially sided with the larger states, changed his vote to force a tie.

A calming voice

“The tie vote … gained time for tempers to cool and compromises to be made,” wrote UGA professor Albert B. Saye in the biography “Abraham Baldwin: Patriot, Educator, and Founding Father.”

Baldwin then served on the special convention committee that crafted the “Great Compromise,” which led to the current configuration of the U.S. Congress — equal representation in the Senate, apportionment based on population in the House of Representatives.

A 7-cent U.S. Postal Service stamp honoring Baldwin was released in 1985 as part of the USPS Great Americans series.

“At a critical moment … Baldwin is credited with having saved the convention,” Saye wrote.

Baldwin “understood the need to calm things down in a room where people were often in loud disagreement with each other,” Deaton said. “He had that ability to bring people together.”

Baldwin was one of only two Georgians to sign the Constitution. He later helped draft the Bill of Rights.

Baldwin served without pay as UGA’s president until 1801, during the institution’s formative years. He died in 1807 while a U.S. senator from Georgia.

Shortly after his death, a Washington newspaper praised Baldwin: “He originated the plan of the University of Georgia, drew up the charter, and with infinite labor and patience, in vanquishing all sorts of prejudices and removing every obstruction, he persuaded the assembly to adopt it.”