When Tom Reichert picks up a magazine or sits in front of the TV, the researcher in him can’t help but take over. Advertising is his thing and no ad, especially those that contain a sexual aspect, is safe from his discerning eye.

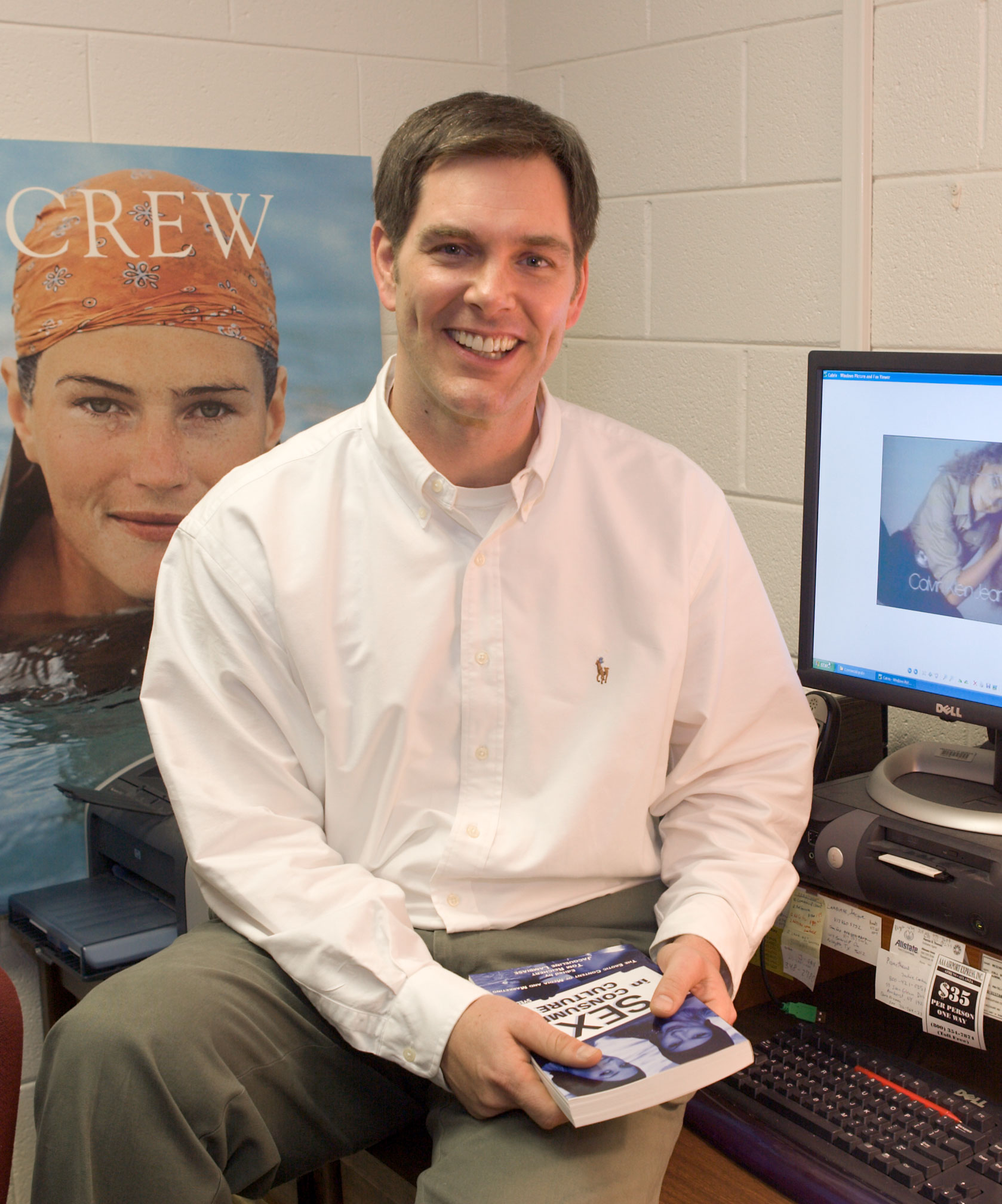

Reichert, an associate professor of advertising in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, has made a name for himself studying the content and effects of sex in advertising and the media.

In his groundbreaking book, The Erotic History of Advertising, Reichert documented the history of sex in advertising and offered many visual examples to demonstrate that sex in advertising is far from a recent fad.

“People are often surprised to see ads from the 1880s and early 1900s that are just as sexually suggestive and scintillating as present-day advertising,” he says. These early images, however, weren’t available to everyone and weren’t targeted to young people.

Reichert’s recent research has found a substantial increase in advertising that sexualizes and objectifies women, particularly in men’s magazine ads.

“From 1993 to 2003, 78 percent of women depicted in men’s magazine ads were sexualized, compared to 40 percent in the previous decade,” he says.

While Reichert found fewer sexy ads in mainstream publications and women’s magazines, he says that “it’s just leaving the mainstream and finding its way to better targeted audiences. Advertisers are just getting smarter about it.”

Advertisers are better targeting their sex-tinged ads toward teen young adult males. Magazines, and in particular the “Playboy Lites” like Maxim, FHM and Stuff, are the mass media of choice for this audience, according to Reichert.

“No one who reads these magazines is going to complain about the sexy ads,” he says. “It’s a receptive, safe audience for advertisers.”

Reichert’s latest book, Sex in Consumer Culture: The Erotic Content of Media and Marketing, takes a pioneering look not only at how sex is used to sell consumer products but at how sex is being used to sell media products such as music, television programming, film, magazines and video games. The 2006 book is the first to blend the two areas of mass communication scholarship, which often looks at indirect societal effects, with advertising scholarship.

When he’s not studying sex in the media, Reichert’s other research interests include media and politics, as well as social marketing. At Grady College, his teaching specialties include advertising courses such as media planning and introduction to advertising. His latest work-in-progress is a Web site (sexinadvertising.com) established as an online source for sex in advertising research, history and commentary.

Although Reichert occasionally takes some good-natured ribbing for the “sexy path” his career has taken, he counters that job security is on his side.

“There will never be a day when sex isn’t used as a strategy to sell products and brands,” he says. “Sex sells and always will. It ebbs and flows depending upon what’s going on in society, but as long as people desire relationships with others, sex in advertising is going to be there.”