In Paris, Georgia-born Eugene Bullard was recognized for valor in the French Air Service, made his name as a professional boxer, mingled with the literary and musical elite, married into a wealthy French family and was the toast of Montmartre. He rubbed elbows with Josephine Baker and Louis Armstrong and gave Langston Hughes a dishwashing job at one of the clubs he owned. Ernest Hemingway based a minor character on him in The Sun Also Rises.

But when Bullard moved back to America after Hitler conquered France, he was seen as just another black man. Treated as a second-class citizen, he spent his last years in obscurity working for racial justice.

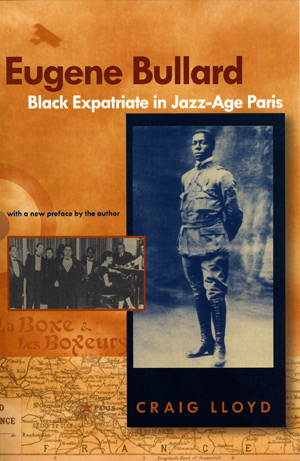

The life of Bullard is told in Craig Lloyd’s Eugene Bullard, Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris. Readers learn of the eventful 25 years he spent in Paris and of his impoverished childhood in Columbus. His mother died when he was 7, and soon after he witnessed the near lynching of his father. When he was about 11, he left home and traveled with gypsies; as a teenager he stowed away on a merchant ship to Europe. Lloyd writes one of Bullard’s friends said he kept his adventurous spirit to the end, when he finally succumbed to cancer in 1961: “He died just as he had lived-just as game as hell.”