The American dream of achieving prosperity requires hard work and sacrifice, and some Americans pay a higher price for that dream than others, according to a new study from University of Georgia researchers.

A team led by Gene Brody found that Black young adults who grew up amid economic hardship and exposure to racial discrimination experienced physical deterioration that persisted through adolescence and well into adulthood—even though on the surface, they were successful.

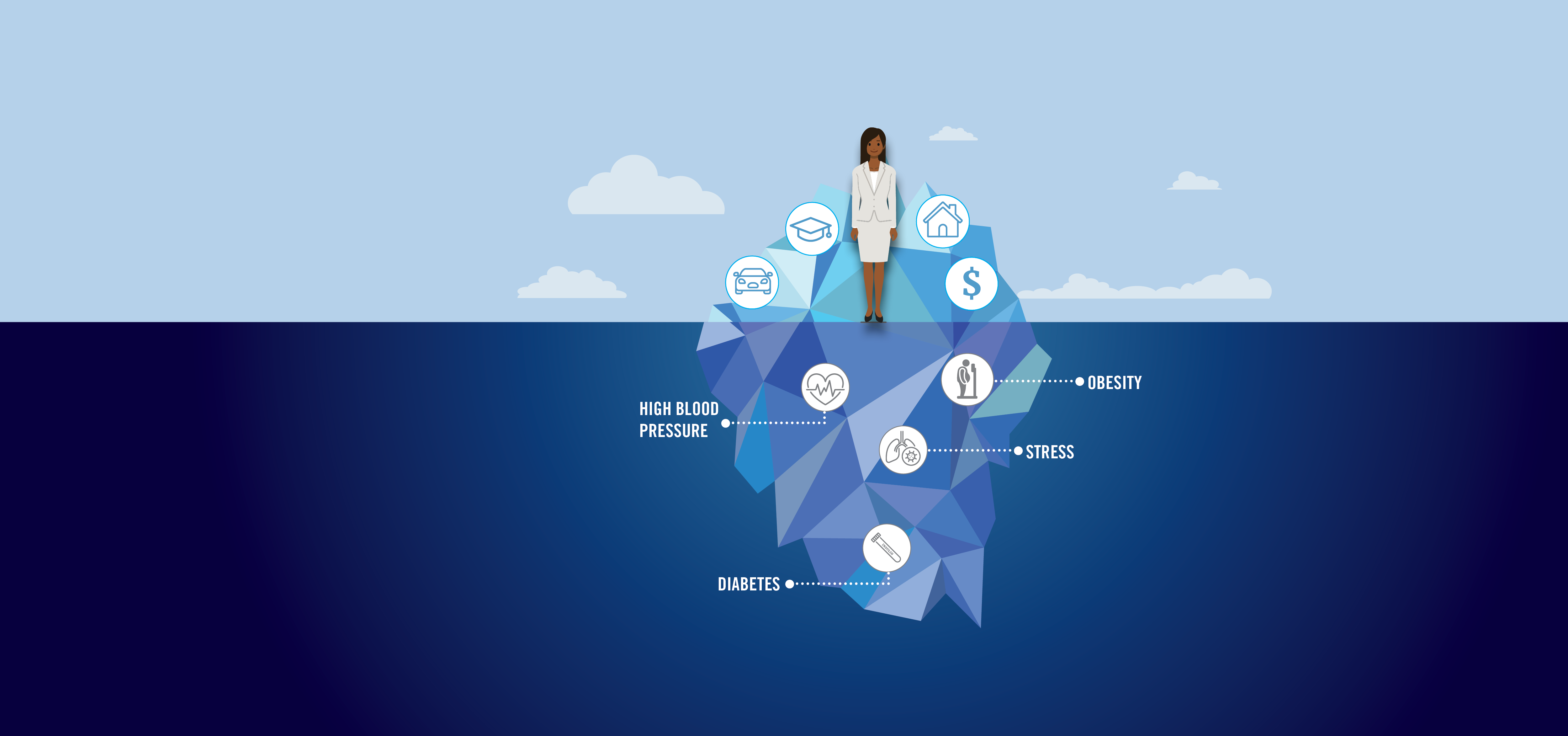

Brody calls this “skin-deep resilience.” A person may look successful on the surface, he said, but evaluations of physiological functioning—what’s happening beneath the skin—are necessary to get a true picture.

Risk factors

“Black adults develop the chronic diseases of aging—heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes, some cancers—at earlier ages than do white adults. Up till a few years ago, we thought these diseases developed during middle age,” said Brody, a Regents’ Professor in the Owens Institute for Behavioral Research and director of the Center for Family Research. “In fact, their origins take place earlier. Our team has found that Black young people who grow up in economic hardship are more likely at the end of the adolescence to show risk factors for later chronic diseases.”

In the study, published in Health Psychology, the researchers found that a group of successful Black adults in their late 20s were more likely to have insulin resistance—a primary risk factor for the development of diabetes—and components of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of risk factors that predicts cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer and earlier mortality.

We found that having this pattern of above-the-skin resilience but below-the-skin deteriorating health was most likely to be found for kids who had to fight their way out of poverty to achieve success.” — Gene Brody

Brody and his team first began working with the group, which included 489 Black children aged 11 from rural Georgia, through CFR’s Strong African American Families Healthy Adults Projects. Despite living in challenging circumstances, including economic hardship and exposure to racial discrimination, the children were reported by their teachers to be doing well based on evaluations of academics, friendships and emotional/behavioral issues.

Eight years later, when the kids were 19, the researchers found that they still appeared to be successful, as reflected in less drug use, lower levels of depressive symptoms and enrollment in college. But blood tests revealed higher blood pressure as well as higher levels of stress hormones, inflammation and obesity.

Affecting health

The new study assessed the group at age 27 and found the persistence of skin-deep resilience. These young adults were more likely to have earned college degrees and less likely to be depressed or have behavioral problems, but blood tests revealed they were more likely to have insulin resistance and components of metabolic syndrome.

“We found that having this pattern of above-the-skin resilience but below-the-skin deteriorating health was most likely to be found for kids who had to fight their way out of poverty to achieve success,” said Brody, who was appointed Regents’ Professor in 2004. “We have found it mainly for Black children, whose quest to succeed is more difficult, given circumstances like discrimination and poverty, than it is for white children.”

The researchers will evaluate these young people next in 2021. The SHAPE program has been continually funded by the National Institutes of Health since 1989.

Co-authors include Tianyi Yu, assistant research scientist and statistician at CFR, and Edith Chen and Gregory E. Miller, both of Northwestern University.