A defining moment in Sonja R. West’s professional life was when she realized that, even more than she wanted to be a reporter, she “wanted to defend reporters and their First Amendment rights.”

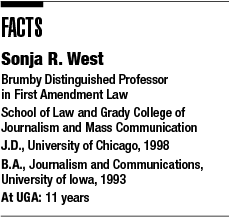

This idea began to take root when she was in college studying journalism and grew while she was working as a reporter. It eventually led to her obtaining a law degree and, ultimately, to her current position as the Brumby Distinguished Professor in First Amendment Law, which is a joint appointment with the School of Law and Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

“I’m somewhat unusual among lawyers because I ended up doing exactly what I went to law school to do—writing and teaching about legal rights and protections for the press,” West said.

Her recent scholarship has garnered significant recognitions from her peers. She received the 2016 National Communication Association’s Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression and the 2017 Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication’s Stonecipher Award for Distinguished Research on Media Law and Policy.

Her recent scholarship has garnered significant recognitions from her peers. She received the 2016 National Communication Association’s Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression and the 2017 Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication’s Stonecipher Award for Distinguished Research on Media Law and Policy.

In the first of these award-winning articles, West addressed the ways reporters are different from individual speakers and argued that “the Supreme Court should recognize unique constitutional rights and protections for the press” that are rooted in the First Amendment’s Press Clause and are not necessarily covered under freedom of speech.

In the second article, she took a historical look at how the framers of the Constitution “saw press freedom as having overlapping objectives. One objective was to secure the right of individuals to publicly express their thoughts and opinions. The other, more structural objective was to ensure that the press could inform the public about important matters and act as a government watchdog. They believed a free and independent press would strengthen our democracy,” West said.

West sees her work as part of the current public debate about the role of the news media in society.

“The modern embodiments of that original structural role are those speakers whom today we call journalists,” she said. “Because journalists play such a vital role in our democracy, the law should recognize that they have unique needs and face unique obstacles.”

For instance, she explained, reporters might require additional abilities to gain access to government information or special protections to shield confidential sources.

“There is also an increased risk that the government will target journalists more than other speakers,” she added.

Another problem, according to West, is that “the line has blurred between who is the press and who is not. It used to be that you knew who the press was because they were the people on TV or who wrote for the newspaper. But now we have blogs and online publications, and everyone is on Twitter.”

This blurriness does not mean that the law should not protect the press, West said. “It means that we should focus even more on identifying the speakers who are consistently and effectively doing the constitutional work of informing the public and checking the government.” The public’s awareness of and appreciation for the press has been increasing, West said.

At the end of the day, this former U.S. Supreme Court judicial clerk said she hopes all her students come away understanding that the law is really about human beings.