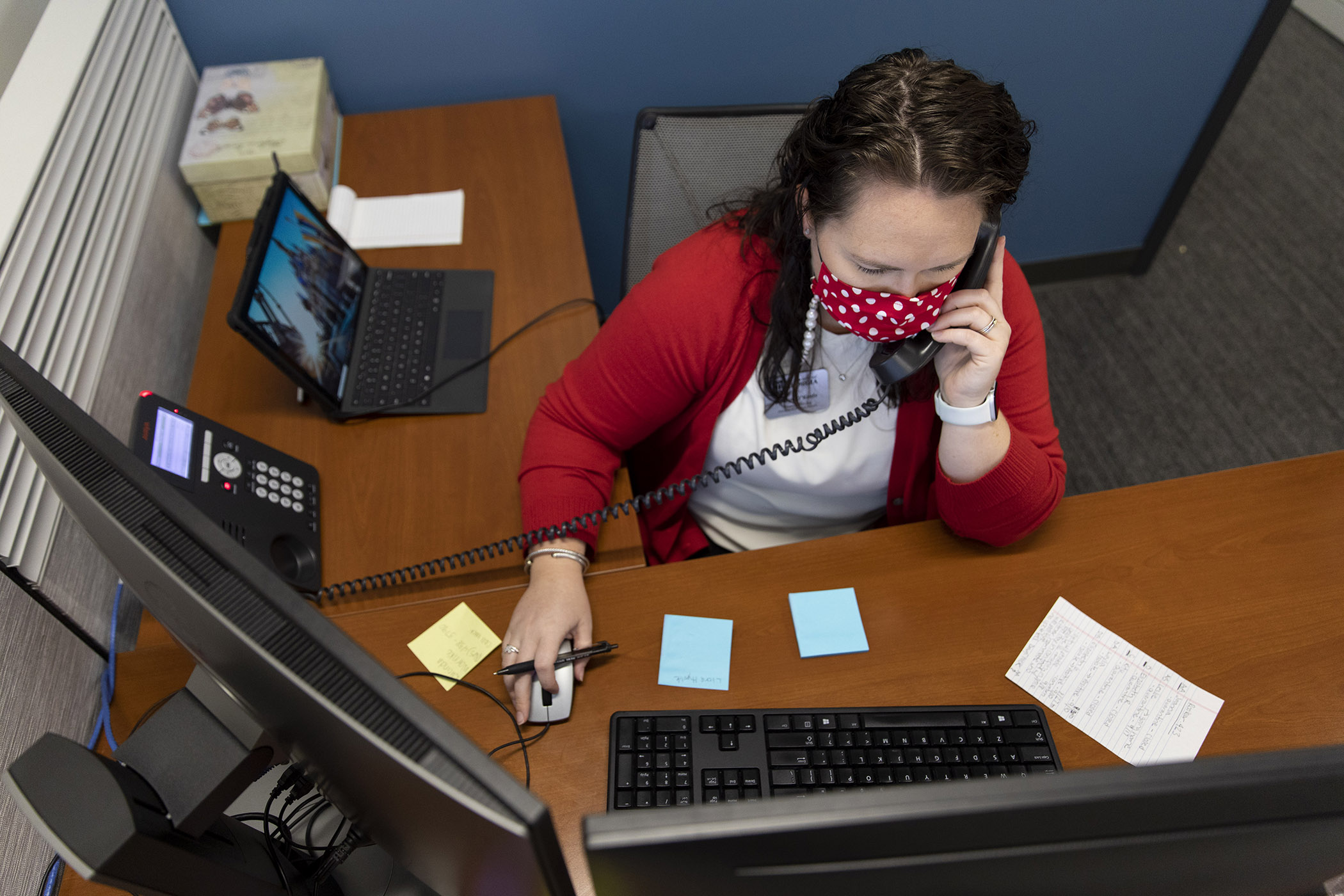

In a two-room space at the office of University Housing, five people speak on the phone to students. They all wear masks and sit at desks behind plexiglass shields. They peer at color-coded spreadsheets on the screens in front of them where they type notes. They are doing important work: helping students who have COVID-19 – or who have come in contact with someone who does – secure a space to quarantine or isolate.

“Your test was negative?” asked Daniel Faria, whose job is to reach out to students flagged in DawgCheck, the University of Georgia’s online portal where students, faculty and staff report symptoms each day before being cleared to come on campus. He was on the phone with a student who came in contact with someone who has COVID-19. “Well, that’s good to hear. I know you haven’t reported any symptoms, but you are still going to need to quarantine. If you need anything, don’t hesitate to reach out.”

Quarantine and isolation are often used interchangeably, but their meanings are slightly different. Isolation separates people with COVID-19 from people who are not sick. Quarantine separates and restricts the movement of people who were exposed to a person with COVID-19 to see if they become sick.

If a UGA student tests positive for COVID-19, they must isolate for 10 days from the onset of symptoms. Once symptoms begin to improve and they haven’t had a fever for 24 hours, they may end isolation. Of course, students should always seek medical advice when they have questions.

If a UGA student has been exposed to someone with COVID-19, they must self-quarantine for 14 days. They aren’t able to test out because the virus has a 14-day period of incubation, meaning a negative test doesn’t signal they are in the clear.

“We’ve had students who don’t understand what quarantine means and why it’s important, especially if they test negative. It’s that educational piece that’s really key,” said Kaitlyn O’Keefe, assistant director of Brumby, Creswell and Russell halls, who manages the call center every Wednesday.

“If going home is the best option for students, we support that,” said O’Keefe. “Or if they have their own private space and bathroom, they can stay put. But there are all sorts of reasons why students can’t go home. Many are from out of state. Some live in multigenerational households or have family members who are immunocompromised.”

Becca Morgan’s role at the call center is to check in on students – via phone – once they are set up in a spot for quarantine or isolation. “Most students have said they’re doing pretty well. Often when I follow up, they are kind of bored and ready to be done. The ones who don’t feel well are so happy we are reaching out to them and helping them get everything set up. Students appear very thankful that we check in and make sure they’re doing OK.”

“We’ve definitely worked strategically to perfect the system, and I think we’ve found a way that is efficient and provides structure to our staff and students, who know what to expect when they get a call from us,” said O’Keefe. “Sometimes they call us before we get a chance to get in touch with them. So they are being proactive, which is exciting.