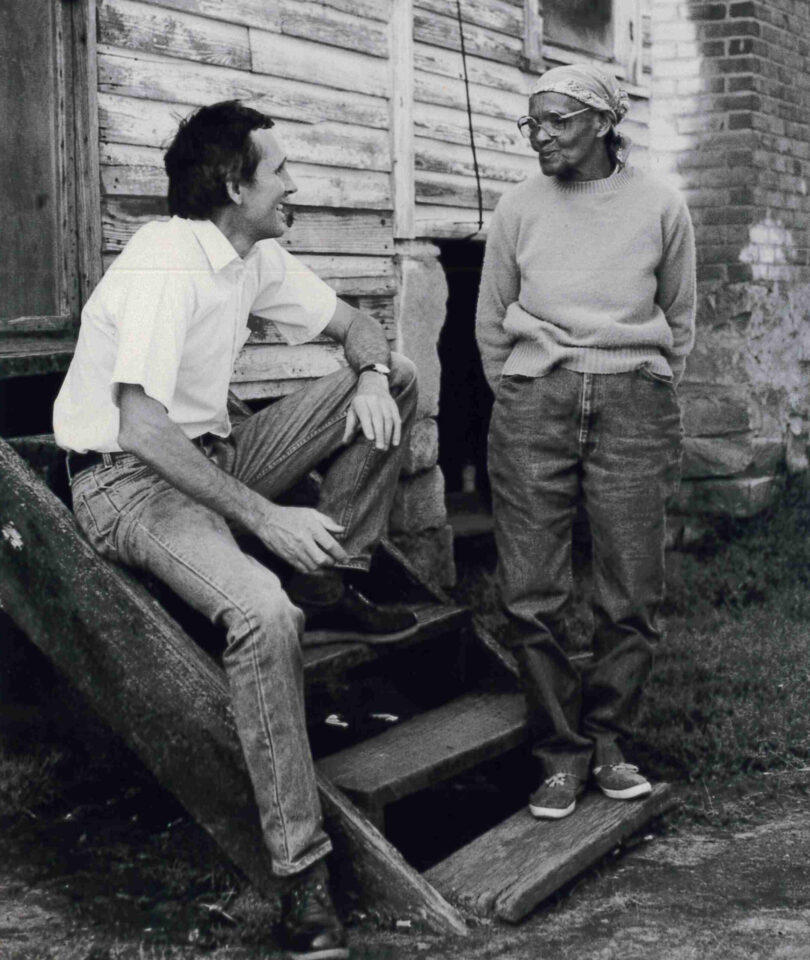

Magnolia Moses, who lived in Oglethorpe County, Georgia, is among several rural African American residents featured in Richard Westmacott’s 1992 book and exhibition titled African-American Gardens and Yards in the Rural South.

It is on display and available for public viewing Aug. 20 through Oct. 15 at the College of Environment and Design’s Circle Gallery, which is located in the Jackson Street Building. The gallery interior is currently closed, but the display may be seen through the interior glass windows. Please wear a mask and keep safe distance from others when visiting.

Until the 1990s, much of the study of gardens in the American South concentrated on those of the elite and powerful—leisure gardens of ornament that added grace to an estate or homestead. These gardens emphasized the visual impact of Anglo-European landscapes—think of the highly formal gardens of Versailles in France or Blenheim Palace gardens in England—and conveyed the wealth of the owners.

Vernacular landscapes—spaces created with only local materials available to the people who live on-site—are also part of the rich history of Southern gardens. Westmacott’s groundbreaking study shone light not only on the fascinating uses of these vernacular spaces, but also on the values of the people who lived there and maintained the gardens: ingenuity, self-reliance, hospitality and generosity.

The gardens featured were actual living and working spaces where many activities take place, from family gatherings to shelling peas to long talks with neighbors. Their aesthetic was directly tied to the work and pleasure married in these “outdoor rooms.” One standout feature was the swept ground, which made it easier to see unwelcome guests, like copperheads and rattlesnakes, and aided in fire prevention by preventing dried plant materials from growing too near the foundations of a home’s raised wooden structure. Not only was the cleared, sandy yard a practical characteristic, but it was a cultural connection to the past: the swept yard was a direct import from life in West Africa where many enslaved Americans came from originally.

Westmacott’s book addresses three essential questions: How do rural African Americans manipulate space? What factors or conditions influence the use of these spaces? Why has the use of yard garden space changed through time?

The gardens, Westmacott argues, trace the conditions of enslavement, tenancy and land ownership. They are not simply outdoor sites of respite; they are evolving landscapes that tell important stories of a history that was largely ignored until the last decade of the 20th century.

Westmacott, who taught landscape architecture for many years at UGA, was born in Singapore and raised in England and received an MLA degree from the University of Pennsylvania before joining the faculty at the College of Environment and Design. He and his family settled on an early 19th century farm in Stephens, Georgia, in 1977, where he became friends with local people living off the land. Moses, who was part of the inspiration behind African-American Gardens, was an immediate neighbor who became a good friend and mentor.

For more information about the display or Westmacott’s book, contact Melissa Tufts, director of the Owens Library and Circle Gallery at the College of Environment and Design, at mtufts@uga.edu. Learn more about the Circle Gallery at https://ced.uga.edu/resources/circle_gallery/.