The Amoeba Summit in Orlando last year is where the importance of her work on drug discovery for deadly amoebae really hit home for Cassiopeia Russell.

It was there she learned the story of an 11-year-old boy who had gone on a family vacation to Costa Rica and was having a great time going down a waterslide at a hot spring there. Days later, he started complaining of a terrible headache. Then he started vomiting. Within a week, he was dead. The cause was a microscopic organism, Naegleria fowleri, living in the warm waters of the spring.

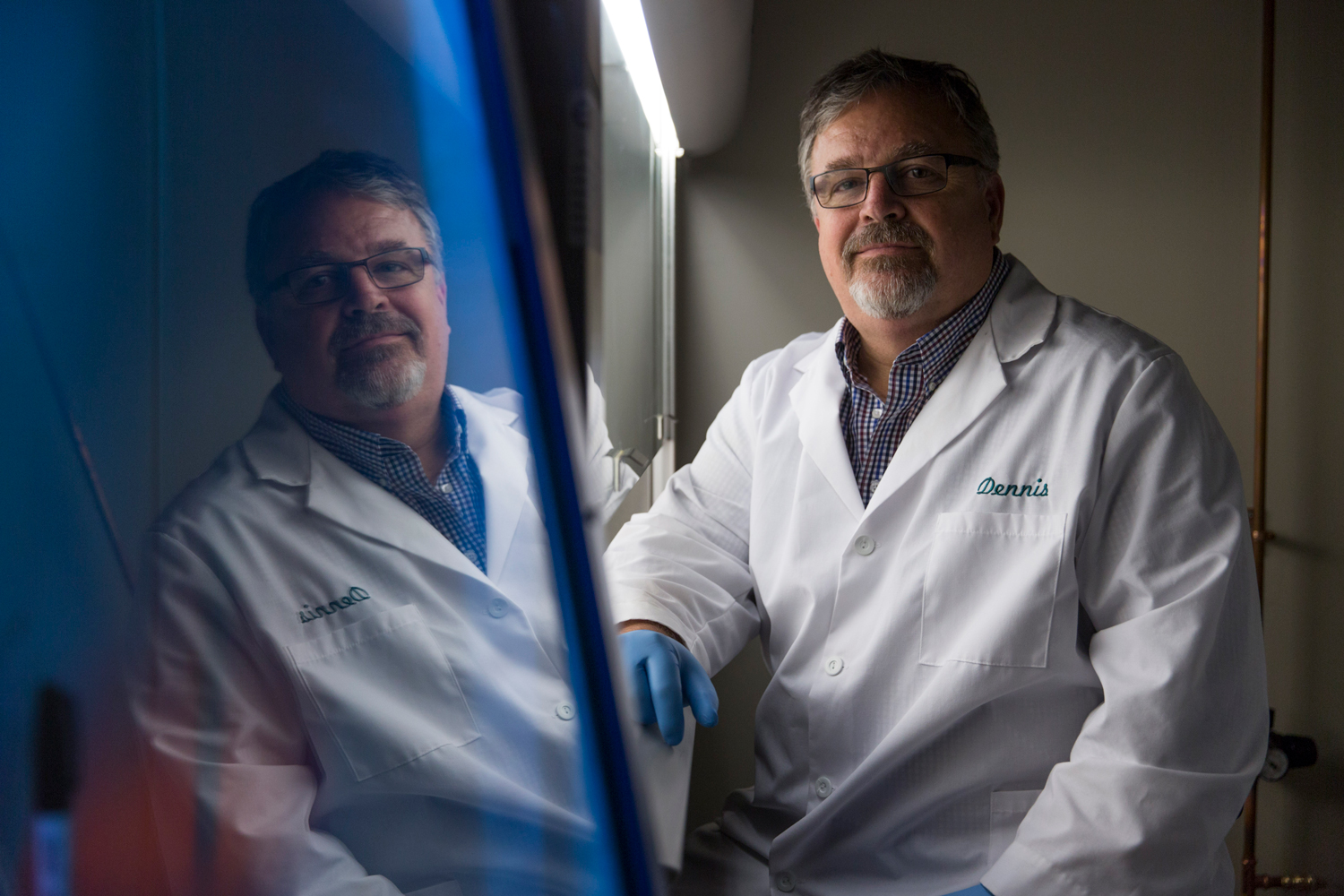

Russell, a doctoral student, had been working in the lab of Dennis Kyle, director of the UGA Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases, for about a year when she was able to attend the conference thanks to a Georgia Research Alliance (GRA) endowment and learn how the research she does in the lab is making a real impact on people’s lives. The GRA was founded with the goal of expanding Georgia universities’ ability to conduct high-level research with the potential of bringing new and innovative products to market. Kyle is the GRA Eminent Scholar in Antiparasitic Drug Discovery, and his endowment enables him to run a 16-person staff of student researchers, postdocs, and research scientists.

“I asked myself at the beginning if I really wanted to work on a parasite this rare,” Russell says. “But if you look at the statistics, this parasite infects mainly young children. Hundreds have died.” She thinks about that every day in the lab.

More commonly referred to as the brain-eating amoeba, Naegleria fowleri is a surprisingly common amoeba found in warm water lakes, ponds, and rivers. When water is forced up the nose—like when diving into a body of water or repeatedly riding a waterslide—the parasite travels to the brain, where it attacks the organ’s cells. Though infections are rare, the brain-eating amoeba kills almost everyone it infects.

One reason Naegleria fowleri is so deadly is because symptoms of the infection resemble those of viral meningitis, a much more common and more treatable disease. “That misdiagnosis and waiting to see if the patient gets better after beginning treatment is wasting valuable time,” says Russell. She’s committed to finding faster, more effective ways to diagnose the condition so patients can get the right medications in time to stop the disease’s progression.

The Georgia Research Alliance really helped me set up this whole operation when I got here. Without the GRA, there’s no way that I could have had this team going for three years.” — Dennis Kyle, GRA Eminent Scholar in Antiparasitic Drug Discovery

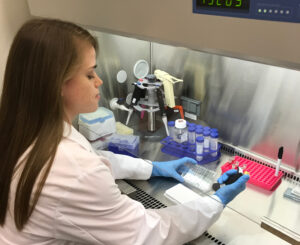

As a member of Kyle’s lab, Russell also tests drug compounds to see which ones can kill an amoeba without destroying the human cells it infects. Current drugs used to treat the infection aren’t very effective and are highly toxic.

Despite being almost 99% fatal, not many federal dollars go toward research on brain-eating and other kinds of amoebae. That’s where the Georgia Research Alliance comes in.

“The Georgia Research Alliance really helped me set up this whole operation when I got here,” says Kyle. “Without the GRA, there’s no way that I could have had this team going for three years. This is something that we have concerns about in Georgia. Every summer, we hear of Naegleria fowleri cases on the news. But we don’t have many people worldwide working on it and very few doing the drug discovery needed to come up with a new drug that could save lives. And that’s really our goal.”

The other main area of research in the Kyle lab is malaria and how the parasite becomes resistant to the drugs commonly used to treat it. Additionally, a less commonly studied strain of malaria can go dormant inside its host, effectively hiding in the liver until flaring up weeks, months, or even years later. Kyle and his team were able to develop a model that simulates that dormant phase to test a variety of drugs to find a way to kill the parasite.

But in order to use that model, researchers in the lab must collect parasites from the field. The endowment helped the lab send assistant research scientist Steven Maher to Asia 25 times over the past four years to work with partners in Cambodia and Thailand.

“International travel has definitely changed my life,” Maher says. “Right now, we’re supporting people in Asia and their families, and I think having that human connection is really important. I think all too often we do research and we forget about ‘how is what I’m doing helping real people?’ I think a lot of researchers would benefit from that type of experience.”

The Georgia Research Alliance, private donors, and the UGA Athletic Association are committed to providing researchers like Russell and Maher with opportunities to advance their work on deadly infectious diseases threatening nations around the world.