It’s like something out of the movies.

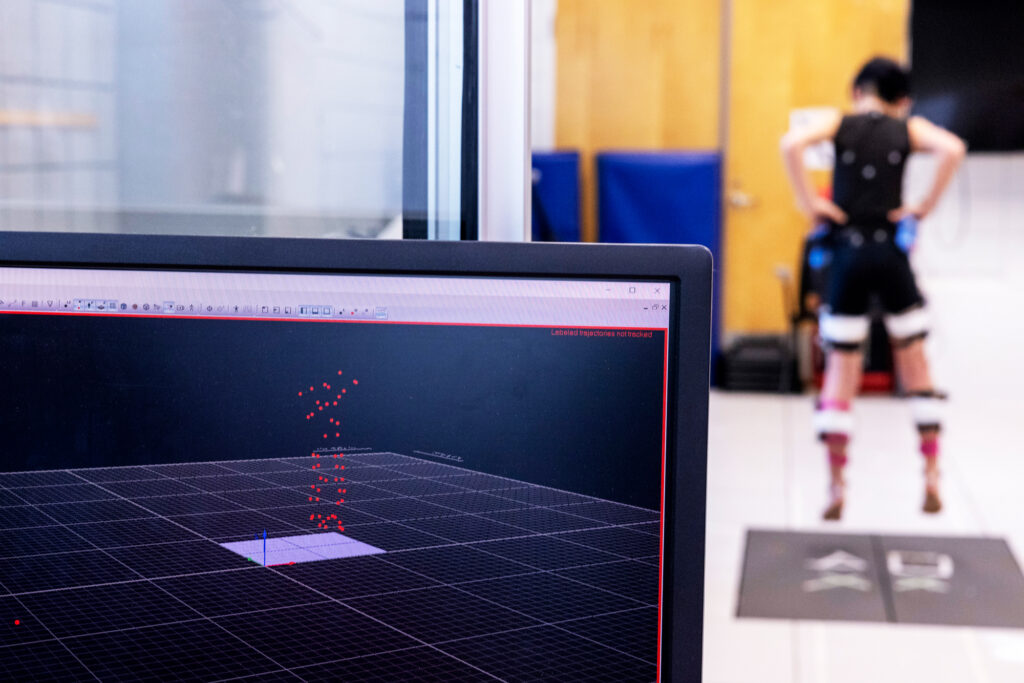

Noah steps into the room, suited up in black athletic wear. Starting at his feet and moving up to his neck, two graduate assistants take turns sticking small, reflective markers on him—about 50 in total. They reinforce the markers with tape and attach six larger, blinking sensors to each leg. One person wraps the sensors in black felt while the other ties a thick band around Noah’s forehead.

When they step away, Noah* rolls back his shoulders and shakes out his arms. He looks ready to take on a supervillain.

Cameras around the room record the movement of the markers as Noah walks, jumps, and stretches. A computer translates the data into a figure of yellow lines and blue dots, matching Noah step-for-step.

Hollywood uses this technology to capture realistic human movement for CGI characters and monsters on the big screen (think the apes in Planet of the Apes or Gollum from The Lord of the Rings). But in the Neuromusculoskeletal Health Lab at the University of Georgia, this data may help improve lives.

Noah was born with cerebral palsy (CP), which affects his muscles and coordination. His right leg is more rigid than his left, and his right hand is weaker. But you might not know it just by looking at him. His CP is mild, which means he can do things like play baseball, his favorite sport.

“He’s an athlete at heart,” says his mother, Cindy.*

Noah’s first word was “ball.” As a toddler, he could sit through an entire Washington Nationals game, and he started playing T-ball as soon as he was old enough.

Noah’s condition doesn’t prevent him from running the bases, but it does affect his everyday life.

“He straddles both worlds,” Cindy says. “He looks and acts like a neurotypical kid, but he has to work very hard to participate in activities that most kids do without thinking.”

Noah was diagnosed at 2 years old. Now 9, he’s taking part in a UGA study to test the effectiveness of a new treatment that, if successful, could help him and other children with more severe forms of CP.

Living with Cerebral Palsy

CP results from an injury or malformation in the brain before, during, or shortly after birth.

“Because it occurs so early, the impact is dramatic,” says Christopher Modlesky MA ’95, PhD ’02 (right), the Georgia Athletic Association Professor of Kinesiology in the Mary Frances Early College of Education and the study’s lead investigator.

CP affects muscle quality, bone health, and motor skills. Roughly 75% of children with the condition experience spasticity, or muscle stiffness, making it difficult to move. It can also cause uncontrollable movements or loss of balance and coordination. Many children, like Noah, experience a combination of these effects.

Treatment options vary as much as the condition does, and the costs add up. Botox injections may help temporarily relax overactive muscles, and surgery can correct posture and misaligned joints. Physical therapy can also help, but more research is needed, Modlesky says.

“There are not nearly enough people who could recognize CP and recognize it early enough where children can get the support they need,” he says. “And for those who get support, we don’t know enough about what the most effective treatment strategies are.”

The clinical trial is taking steps to change that. Forty-four children like Noah, aged 5 to 11, visit the lab five times over a year. Researchers collect data to assess their movement, muscle strength, dexterity, balance, and other measures during sessions that last up to two days. But the study’s primary focus is an alternative treatment: whole-body vibration therapy.

“There are preliminary studies suggesting that vibration has a positive effect on muscles and on balance,” Modlesky says. “The focus of this study is to look at a mild vibration intervention and determine if it can improve muscle size and quality and if it can improve balance, ultimately increasing the child’s participation in physical activity.”

Participants stand on a small, square platform that looks like a scale. When activated, it emits almost imperceptible vibrations that travel from the feet to the head. Electromyography sensors track muscle responses as participants bend, jump, and balance, recording changes over time.

Breaking it Down

This is Noah’s second visit to the lab. He will return twice in the summer and again next January for his final session. The family travels from out of state to take part, but for his mom, the distance is more than worth it.

“Typical medical doctors have been pretty dismissive because his case is mild, and he doesn’t deal with the common medical complications that come with CP,” she says. “Having the people at UGA as a resource and knowing they are working to improve the lives of kids like [Noah] gives us so much hope. They understand at a scientific level what is going on in his body and have helped explain it to me when no one else has.”

The study results could make alternative therapies like whole-body vibration more accessible and affordable. In the meantime, the lab is helping families learn more about how CP affects their children’s daily lives.

For Owais Khan, a graduate research assistant in the lab, that’s one of the most important aspects of the study.

“We’re giving them more information about their child’s body capacities and abilities while letting them explore a therapy that does not require the sort of financial input that traditional occupational or physical therapy does.”

Originally from Mumbai, India, Khan is a trained pediatric physical therapist. He enrolled as a graduate student at UGA in 2019 to work under Modlesky. The multidisciplinary nature of the lab lets him and other graduate students explore different research areas, from biomechanics to neuroimaging. The facilities and technology within the lab are unmatched, he says.

“We’re using so many different tools to learn about CP from different perspectives; the opportunities are endless. All that’s required is a willingness to put in the work, a desire to work with children, and the initiative to take the first step,” Khan says.

Every student in the lab—seven graduate assistants and six undergraduate volunteers—supports a piece of the study, from writing data analysis programs to conducting tests. They, along with two staff members, dedicate their weekends to working with the children and families in the clinical trial.

Khan found his niche in upper limb rehabilitation. He works with the research participants to measure hand-eye coordination. They use game-like scenarios to make the tasks relevant and fun, like catching a ball, pouring from a cup, or hitting a moving target, ultimately determining if the vibration intervention improves performance over time.

“Almost universally, all the children I’ve worked with have a sort of innate grit,” he says. “I admire their resilience, and I hope to learn from that in whatever little way I can.”

Beyond Mobility

The study, made possible through an NIH grant, is 20 years in the making.

After Modlesky earned his doctorate in exercise science from UGA in 2002, he joined the University of Delaware, where he helped develop new approaches for working with children with CP.

“If you have an injury to the brain, depending on how it happened, it can affect other areas. It can impact your behavior and sensitivities, cause education delays,” Modlesky says.

Last year, Noah’s parents discovered that he struggled with reading. Testing revealed that he may have dyslexia.

“As a mom, you’re always wondering, is the CP causing this, and how else is it manifesting?” Cindy says. “We have to do additional digging to figure out what is going on in his brain.”

In 2017, Modlesky returned to his alma mater as a faculty member to continue pursuing his work through an endowed professorship. The clinical trial employs child-friendly practices he helped develop over the years, including special MRI techniques.

“To make small steps in our research takes a lot of effort, thought, attention to details, and persistence,” Modlesky says.

Living with cerebral palsy takes that too. But Noah isn’t fazed. When he leaves the lab, he’s headed to try out for his school’s travel baseball team. And he’s ready to hit it out of the park.

*Names have been changed to protect privacy.

This story will appear in the Summer 2022 issue of Georgia Magazine.