When asked who is going to win an election, people tend to predict their own candidate will come out on top. When that doesn’t happen, according to a new study from UGA, these “surprised losers” often have less trust in government and democracy.

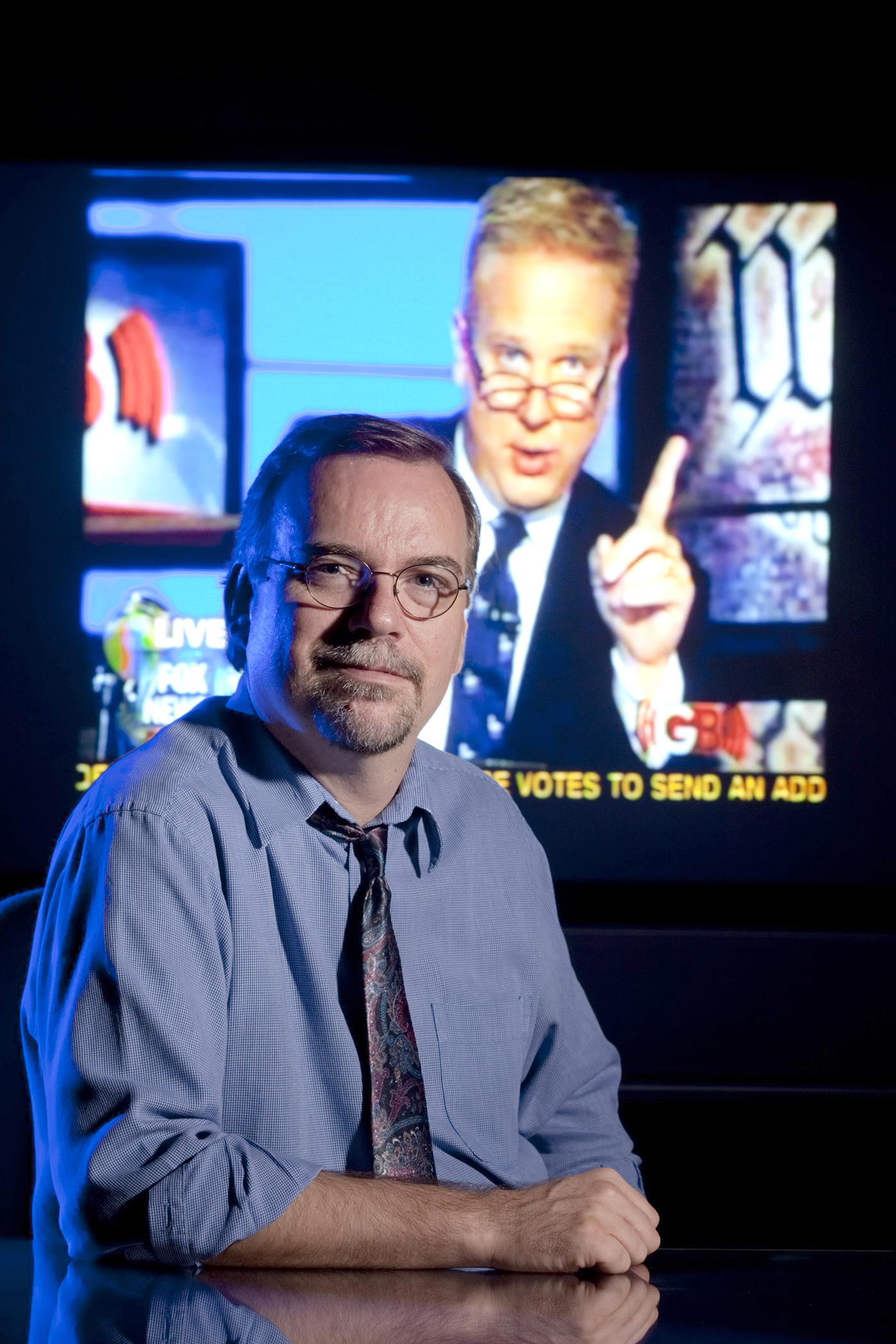

The news media may be partly to blame, according to Barry Hollander, author of the study and UGA professor in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

“You need the trust of those in a democracy for democracy to be successful,” Hollander said. “We have become more fragmented in our media diet and that leads to hearing what we want to hear and believing what we want to believe despite all evidence to the contrary, such as polls. Our surprise in the election outcome makes us angry, disappointed and erodes our trust in the basic concept of democracy; and that can threaten our trust in government.”

Based on the theory of wishful thinking—the idea that people tend to predict their favorite sports team or candidate will win—Hollander analyzed 5,914 survey responses conducted by the American National Election Study before and after the 2012 presidential election. He examined people’s pre-election predictions, their news media consumption habits and ultimately their trust in government and democracy. The results were published in the Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly in July.

He found that “surprised losers,” those who predicted their candidate would win but who eventually lost, are more skeptical of government, democracy and the election process than are expected losers, or those who favored the same candidate but expected to lose. Despite all evidence to the contrary, 78 percent of Mitt Romney supporters during the 2012 election believed he would win. Nearly all polls showed President Barack Obama leading throughout the campaign.

“When predicting an election outcome, people sample themselves, friends, family and Facebook friends,” Hollander said. “You draw a sample of those people like yourself, and we are drawing a very biased sample. In this way, our own preferences have enormous weight.”

In addition to sampling people much like themselves, the media that people draw from can influence their perception. Previous research from Hollander studied the effect of news consumption on political knowledge.

“In theory, greater news consumption should lead to greater political knowledge,” he said. “Therefore, you should become aware of who is winning or losing, and this should reduce wishful thinking. That worked for those who read newspapers, but not for other news media. Also, the stronger you care about the outcome or feel about a candidate, the more likely you are to think that candidate is going to win, regardless of the polls.”

Among Romney supporters, watching Fox News Channel had a unique effect. Controlling for factors such as age, education, race, gender, party identification and exposure to other news, the study found that those who watched Fox News Channel were even more likely to predict Romney would win, and this in turn had an effect on whether or not they thought government posed a threat. In this election, the results suggested if someone watched Fox News Channel, he or she was less trusting of the government.

“The more fragmented our media have become, the more people are hearing what they want to out of their news and the more surprised they are when the outcome doesn’t turn out as they’ve expected, which could further erode trust in elections, democracy and government,” Hollander said. “As a journalist, I didn’t give any thought to my effect on people. The danger is if our media continue to become more fragmented, the more and more we tend to hear only what we want to hear and believe what we want to believe. But when the outcome surprises us, that can have very real consequences—not only in people’s own perception but also in the stability of democracy and government.”