Chickens don’t commute to work and they don’t balance checkbooks, but they do get stressed.

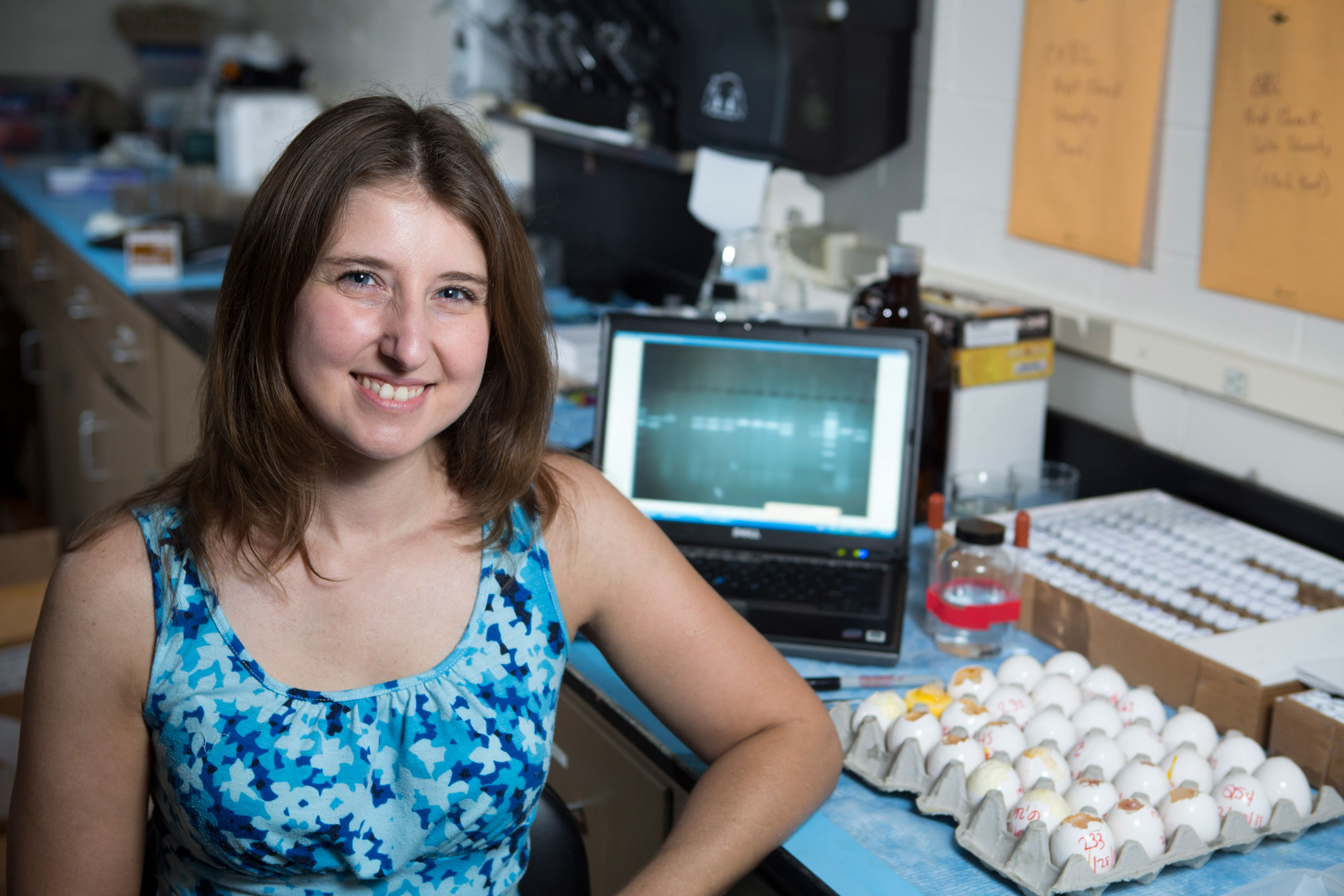

Kristen Navara, an endocrinologist in the poultry science department of the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, is finding ways to help them relax.

Navara has spent her career researching how environmental factors—like diet and climate—affect biological chemistry and how that chemistry, in turn, affects the health and lives of people and animals.

Stressed poultry, like stressed people, experience changes in their body chemistry that affect their health and behavior. Understanding the mechanisms that trigger these changes-and how to prevent them-can change the way we understand the way stress affects animals in general, including people.

In the short term, relaxed chickens are healthier and more productive. Navara says there’s a growing consumer demand for breast and thighs from “happier chickens.”

“Many people perceive bird’s stress through the lens of what they would find stressful,” Navara said. “Birds don’t assess stress the same way that humans do.”

Free-range life might seem like a better life to shoppers, but for chickens-who have a tendency toward cannibalism and fight over resources-free-range life actually may be more stressful. Scientists just don’t know yet, Navara said.

Currently, Navara is working with chickens and finches to test a range of enrichment tools like nesting boxes and shiny bird toys to see what helps the birds relax.

Navara didn’t set out to make chickens more comfortable. She studied biology as an undergraduate and graduate student at Penn State and then Auburn University. She went on to pursue postdoctoral studies in neuroscience at Ohio State University.

Studying chickens gives endocrinologists like Navara and geneticists a good model for research, since they are easy to keep and reproduce quickly.

“We do basic research in a chicken model, but so much of this research can be used to understand other animals or how these issues affect human health,” she said.

For instance, Navara’s earlier research focused on how climate and seasonal changes correlate to different ratios of male and female offspring for many types of organisms, including humans.

She’s extended this sex ratio research further into chickens-where poultry producers are interested in finding out what type of diet would induce hens to produce more female chicks. Diet and stress affect the hormone levels in child-bearing females and can affect the sex and health of the offspring.

For instance, researchers have found that parrots in the wild produce more male offspring when food is plentiful. The physiological mechanism that contributes to that kind of phenomenon is what Navara is trying to decipher through her work with chickens.

When she’s not delving into the inner lives of chickens, Navara teaches undergraduate courses in avian biology and supports teams of undergraduate and high school research assistants who work in the poultry science department each year.

“We are devoted to bringing both high school students and undergraduate students into the lab,” she said.

“I think that’s vitally important because you can’t understand science until you experience it firsthand.”