(Editor’s Note: This story has been changed since its initial publication date.)

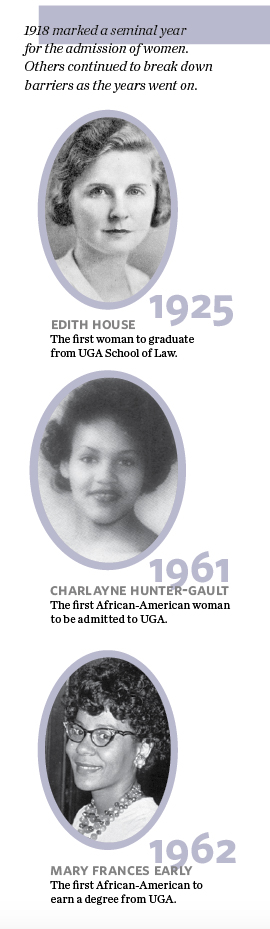

More than 100 years ago, the first class of undergraduate women enrolled at the University of Georgia. Today, it’s hard to imagine UGA without women. In the past century, female students have become part of the essential fabric of the university—leading student organizations, spearheading community outreach efforts, offering diverse perspectives to the learning environment, and teaching and leading university research.

But the path to coeducation was long and difficult. Mary Creswell, the first woman to earn a UGA bachelor’s degree, described it as “prying open the doors of the university to undergraduate women.” It took a 25-year effort from dedicated advocates to break the gender barrier.

1. The Origins

In 1889, a proposal backed by Georgia women’s groups the Daughters of the American Revolution and Colonial Dames appealed to the university’s Board of Trustees for the admission of women to UGA. No action was taken on the proposal and wouldn’t be for years to come. But supporters of coeducation continued their push. A proposal to admit women to UGA finally came to a vote in 1897, but the motion lost 8-5. Again and again, advocates for coeducation, including some members of the Board of Trustees, brought the issue up, but it was repeatedly denied.

Dawson Hall, completed in 1932, was built to house the UGA School of Home Economics, which later evolved into the College of Family and Consumer Sciences.

2. The Opposition

Opponents to coeducation argued that allowing women to study serious subjects alongside men would bring a loss of morality and the end of wholesome womanly qualities. While advocates were arguing that coeducation would give women more confidence and allow them to be less shy, traditionalists were decrying these outcomes. In a News Herald (of Lawrenceville) editorial, one writer noted that teaching women alongside men at the university would bring “the destruction of that modesty and real refinement, which makes them so attractive to men.”

A thread to this argument went that women should not have to face the hard truths that one confronts in higher learning. As UGA Chancellor David C. Barrow, who oversaw the university during the transition of coeducation, explained, “The gentlemen who opposed coeducation did so under the impression that women were too good for the university, rather than that the university was too good for women.”

For his part, Barrow admitted that he too was once resistant to the idea before he realized its value. “Since women are needed in solving the problems of society,” he said, “we must let them have a chance to learn these problems.”

3. Summer Sidesteps

While proposals before the trustees were getting nowhere, some women were finding ways to study at the university anyway. In 1899, Chancellor Walter B. Hill was in favor of the admission of women and even began the process to scout locations to build facilities for women to study, but Hill died before his plans could be realized. However, under Hill’s watch, women did gain access to UGA’s Summer School sessions, which did not require official admission to the university but were taught by UGA faculty.

before his plans could be realized. However, under Hill’s watch, women did gain access to UGA’s Summer School sessions, which did not require official admission to the university but were taught by UGA faculty.

Hill’s successor, Barrow, also opened the door for professors to direct the studies of women between summer sessions. Through these means, Mary Dorothy Lyndon became the first woman to earn a degree from UGA in 1914, receiving her master of arts degree from the Graduate School without ever officially enrolling at the university. Three other women earned UGA graduate degrees like this before 1918.

4. The Opening

Necessity gave the advocates of coeducation the leverage to finally pry the door open.

With America’s entry into World War I approaching, a shortage of trained qualified nutritionists, extension workers, and secondary teachers in the state compelled a majority of the Board of Trustees to finally allow coeducation at the University of Georgia. College of Agriculture President Andrew M. Soule paved the way with the creation of the Division of Home Economics. And in 1918, 12 women enrolled at UGA, all in the home economics program, which eventually became the College of Family and Consumer Sciences.

More enrolled the following year as the Peabody School of Education, now the Mary Frances Early College of Education, accepted female students. And, soon, all programs were open to women.

Read about one of the first women to study ecology at UGA.

Built in 1920, Soule Hall was the first women’s dormitory on the UGA campus. It was named after Andrew Soule, the president of the Georgia State College of Agriculture, who championed the creation of the home economics division and the admission of women at UGA.