The back of a juice bottle contains all kinds of information about your favorite breakfast beverage: calorie content, grams of sugar and the amount of antioxidants in the mix.

But what you don’t see on the nutrition label is how your body will process those nutrients-how much of the juice’s sugar and vitamin content is absorbed by your digestive system.

That is the information that assistant professor Fanbin Kong is after.

“One of the things that I’ve done is studied how food is digested from an engineering perspective because, basically, I’m a food engineer,” Kong said. “So we look at food as a material. How does food’s microstructure affect its digestion? How will hydrodynamic and mechanical forces present in the gastrointestinal tract affect food breakdown and nutrient release?

“This information is very useful in the way we design foods, especially functional foods,” Kong also said. “You can see nothing from their labels. You can see the content, but you don’t know how it’s going to be absorbed by your body.”

Functional foods are products like energy bars, vitamin-fortified juices, nourishment shakes for the elderly and children or milk for people who are lactose intolerant.

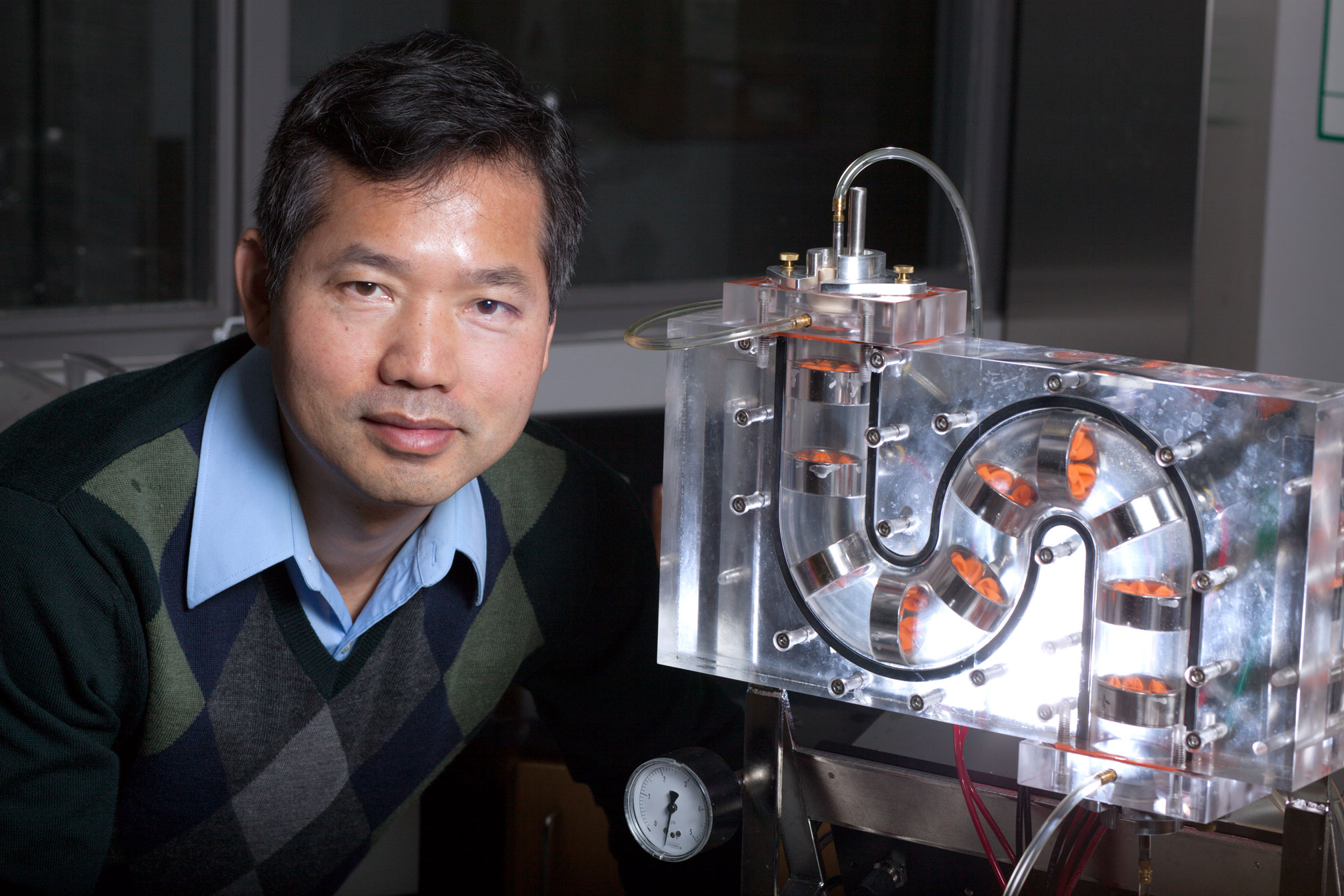

Kong has spent the past several years developing models of the human stomach that realistically demonstrate the way the food breakdown in the stomach is affected by contraction forces from peristaltic movement of stomach walls. Working with the UGA Instrument Shop, he has created a novel model for an artificial intestine. He also is designing a new, more advanced artificial stomach model.

The models are a way to test the efficacy of functional foods and develop foods that help solve some health concerns people face today.

Currently, Kong is focused on how the body extracts phytochemicals-like tannin-from food and how these chemicals affect the way the body absorbs other nutrients. One project involves tannic acid, one type of tannin. The acids have antioxidant properties that are good for humans, but they also affect the way the body absorbs sugar. Tannic acid inhibits the enzyme that allows the body to absorb sugar.

“We are eating tannins every day, but it doesn’t work like we would like it to because the concentrations are low,” Kong said. “Second, when the tannins go through your stomach and intestines, you don’t know how much is released. And third, even when the tannin is released in your stomach, it reacts with the proteins and the enzymes there and you lose that action.”

Kong has developed a way to create tiny beads of tannic acid that can be incorporated into breads and carbohydrate-rich foods. The beads are designed to dissolve in the neutral pH environment of the intestine where 80 to 90 percent of the digestion of carbohydrates takes place.

The tannic acid will inhibit some digestion, so that less simple sugars are produced for absorption, allowing people on sugar-restricted diets to eat carbohydrates without having their blood sugar spike.