Rap is one of America’s most popular musical genres, but research by University of Georgia professor Andrea L. Dennis has found that it also has the distinction of being the only art form that is regularly used as evidence against criminal defendants. Her groundbreaking scholarship has catalyzed a national assessment of a practice that disproportionally affects Black and Latino defendants.

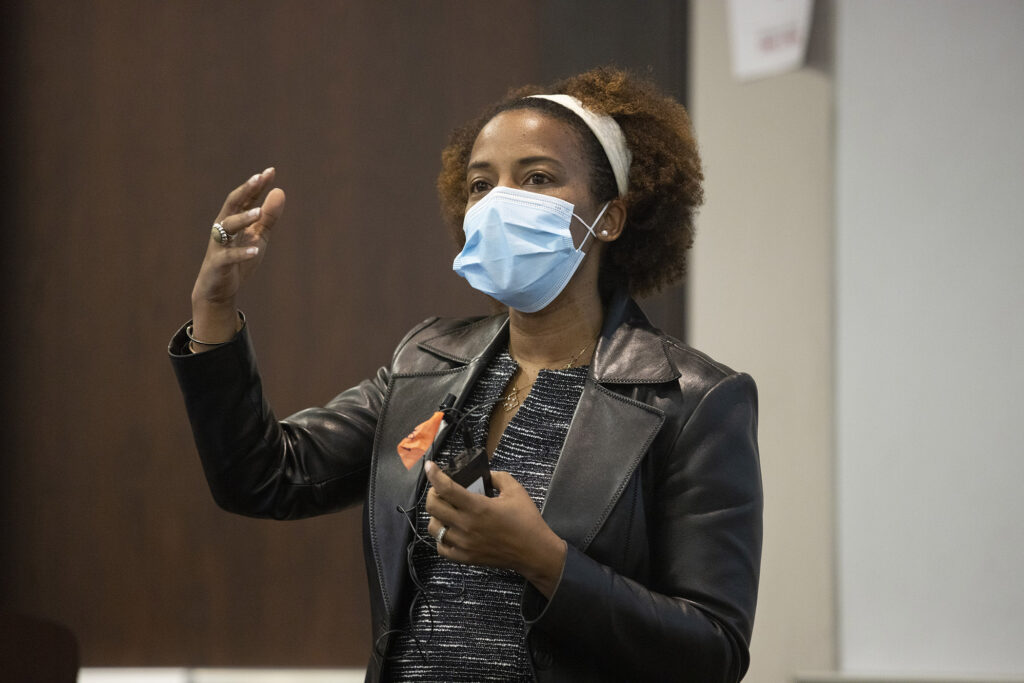

“Whether used as autobiographical confession, evidence of state of mind, evidence of bad character, or as a threat, rap is the only fictional music genre used in this way,” said Dennis, the associate dean for faculty development and John Byrd Martin Chair of Law in the School of Law. “And the use of rap lyrics as criminal evidence is part of a larger and longer history of using racial epithets, racial imagery, stereotypes and narratives to criminalize and convict Black and Latino men.”

Dennis explores the legal and ethical implications of the use of art as evidence in the book, “Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America,” which she co-authored with Erik Nielson, a scholar of African American literature and hip-hop culture at the University of Richmond.

The authors begin with the story of McKinley Phipps, a Louisiana rapper who goes by the stage name Mac. In 2001, Phipps was tried in a case in which prosecutors selectively took his lyrics out of context to help convince jurors of his guilt in a shooting. Despite the fact that numerous witnesses said the shooter in the case looked nothing like him—and that another person came forward and confessed—Phipps was convicted and is currently serving a 30-year sentence. Rather than this being an isolated incident, Dennis found that rap has been used as evidence in at least 500 known criminal cases, some of which sought the death penalty.

National impact

“Rap on Trial” and the issues it raises about inequities in the criminal legal system and the failures of First Amendment protections have drawn the attention of media outlets such as NPR, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Atlantic, among many others. It is also changing how law is practiced in courtrooms across America.

“Little by little, we are reading in court opinions and hearing from practitioners that judges are engaging in more searching analyses of whether or not lyrics should be admitted in cases,” Dennis said. “Sometimes defense attorneys win the arguments for exclusion, but sometimes they still don’t. The increasing willingness to engage in serious inquiry is, however, a significant first step from where we began when this research started 15 years ago.”

One of her recommendations is that defense counsel be permitted to call an expert on rap music to explain, among other things, that lyrics aren’t necessarily autobiographical or true-life stories and that bluster and exaggeration often typify the immensely popular art form.

Nielson, her co-author, has consulted or testified in more than 60 cases to date, and Dennis has found that prosecutors are increasingly withdrawing lyrics as evidence after learning it will be vigorously challenged by the defense.

A holistic approach

“Rap on Trial” has been Dennis’ most prominent work to date, but her scholarship focuses on other areas at the intersection of criminal law, family law and racial justice. Her scholarship reflects her belief, shaped in part by her experience as a public defender and as a civil prosecutor of child abuse cases, that legal doctrine and practice should be examined with an eye toward how it affects the lives of men, women and children.

She takes a similarly holistic approach in the classroom, where she teaches courses such as criminal law, evidence and children in the legal system. “We’re not just simply looking at legal doctrine; we’re not just simply looking at legal theory,” she said. “We’re trying to examine, realistically, how the law is operating on the ground.

“In each class session, I try to make sure that I work through at least one problem with the students that will deepen and complicate their thinking about the assigned material. I try to remind my students that these cases involve actual people in real-world situations. They are not just words or descriptions on a page; they’re not just parties in a case. I try to humanize the ordinary individuals who get caught up in the legal system.”