University of Georgia art professor RG Brown III sloshed knee-deep through the salt marsh, racing against the rising tide to deploy a trapezoidal assembly of white plastic pipe he had named “Spinner.” The sculpture, intended for submersion, would become another element in Brown’s quest to depict familiar objects in innovative ways.

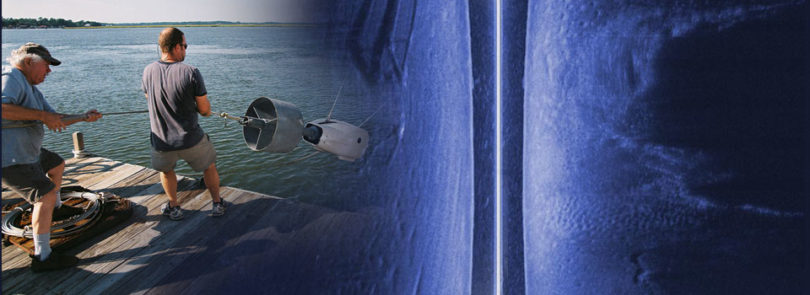

Later, Brown recorded ghostly blue images of the angular sculpture as it lay on the muddy bottom of the Skidaway Island estuary, using a bulky sonar unit towed behind the UGA Marine Outreach Programs research boat Sea Dawg as it cruised slowly down the tidal creek.

Brown, a sculpture professor with the Lamar Dodd School of Art, won a Public Service and Outreach Faculty Fellowship last fall to beam sonar into salt creeks on the coastal islands near Savannah as a creative way to help people see the natural environment from an unexpected point of view. The fellowships offer UGA professors the opportunity to spend an entire semester working with one of the university’s eight public service and outreach units to apply their academic expertise to outreach initiatives.

One product of the fellowship is a ceramic-tile mural based on Brown’s sonar images, scheduled to be unveiled this fall in UGA’s Marine Education Center and Aquarium on Skidaway Island. The artwork-created with one of the tools marine scientists use in their research-will encourage students and other visitors to consider what lies below the surface of the estuary, according to Brown.

“When people see that sonar-image sculpture, it’s going to make them think about the environment in a different way,” he said.

“My primary objectives were to make a work of art and to figure out a way to make this an educational component,” said Brown, who has experimented with sonar imaging for several years in exotic locations like Key West and more prosaic locales like Lake Chapman in Athens’ Sandy Creek Park.

Employing sonar to encourage people to see objects in novel ways grew from an idea Brown got from the ancient Nazca Lines etched into the desert of southern Peru. Standing on the ground, the Nazca Lines seem to be nothing more than shallow trenches gouged across the pebbly desert. But viewed in their entirety from a different perspective-atop the nearby foothills or from the air-the lines become patterns that trace out images of birds, fish and other animals.

At first, Brown covered sculpture under a layer of soil and scanned the installation with ground-penetrating radar as a method of inducing viewers to look at objects differently.

“I had the idea of making objects and placing them in the earth, and using technology to reveal them,” he said. “Here, the idea for me was to try and put sculpture in the water and use the sonar to ‘see’ it.”

To create artistic, instructional images, Brown uses a sonar unit similar to an angler’s fish finder apparatus to beam sound waves through the water and record the echoes. Brown’s sonar surveys detect patterns and shadows that reveal submerged fallen trees, hidden shorelines, the ripples left in creek beds by wave action-and Brown’s sculpture installations.

“The basic premise is that I am an artist and my work is about exploring the way we see things,” he said. “I am intrigued with sonar because it allows us to see underwater in conditions that make it impossible to see through our eyes.”