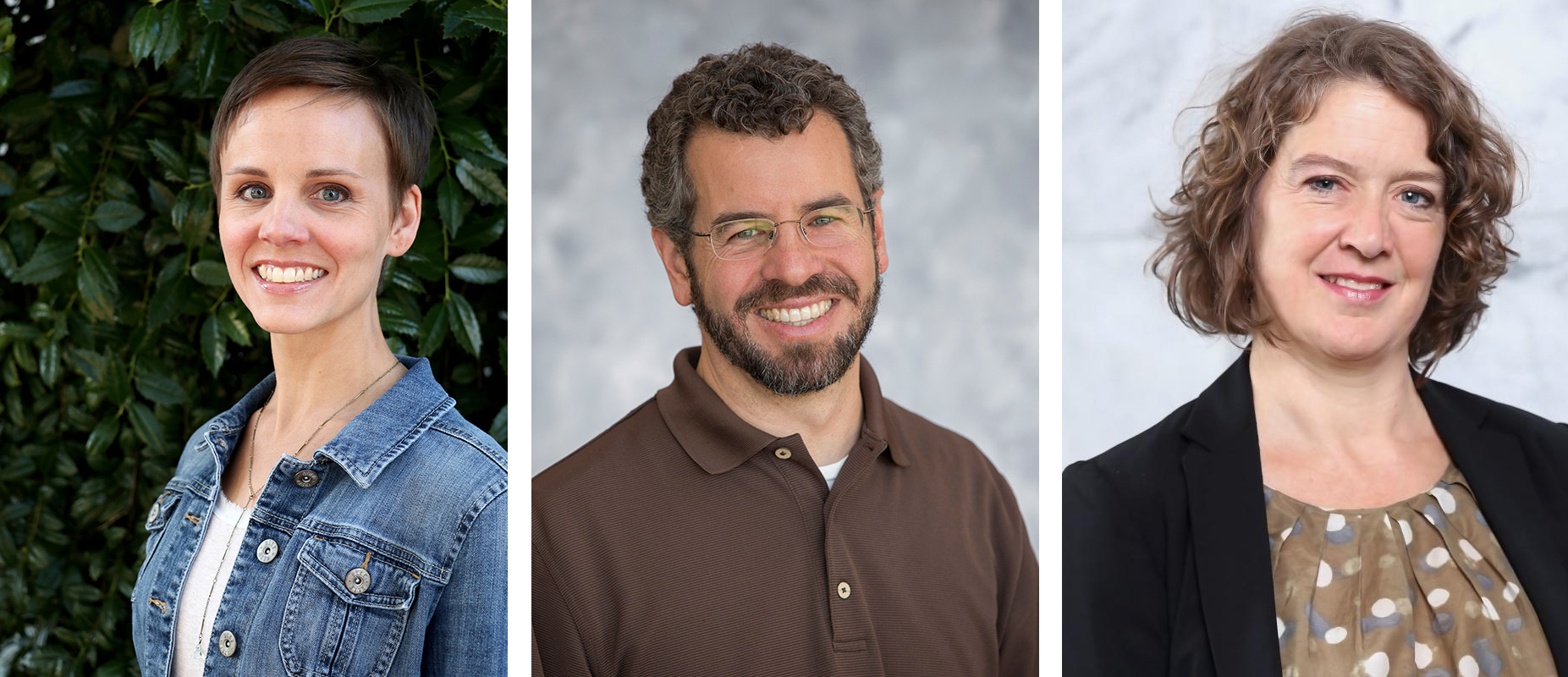

Abigail Borron, Jon Calabria and Elizabeth Weeks served as 2017-18 Public Service Faculty Fellows. They worked to ensure shoreline stability on the coast, address health concerns in rural Georgia and create a way to measure the impact of leadership training.

The Faculty Fellowships offer tenure-track and tenured professors an opportunity to pursue their research through a unit of UGA Public Service and Outreach. These faculty spend the fall semester of their fellowship with the Archway Partnership, the Carl Vinson Institute of Government, the J.W. Fanning Institute for Leadership Development, Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, the Office of Service-Learning, the Small Business Development Center, the State Botanical Garden of Georgia or the UGA Center for Continuing Education & Hotel, conducting applied, community-based, policy or program evaluation research to fulfill an outreach initiative. Most continue working with PSO once the fellowship ends.

The vice president for PSO provides $15,000 to a fellow’s home department, to be spent as the department head deems appropriate.

Applications for the fellowships are accepted in March. For more information, go to http://outreach.uga.edu/programs/pso-fellowship-program.

Abigail Borron

Abigail Borron, an assistant professor of agricultural communications in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, developed quantitative measures to assess the social and economic impact of leadership programming at the J.W. Fanning Institute for Leadership Development.

“We have tremendous programs,” Borron said. “How do we best assess our value in these communities?”

Borron’s goal was to create a research framework that addresses all these challenges and creates a unique profile for communities that include the various opportunities, challenges and barriers that make up a community. Borron used the Community Capitals Framework, a research framework that defines community vitality and sustainability by assessing seven capitals: natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial and built capital. She modified the CFF to measure perceptions of each capital. These capitals were transformed into a numerical scale.

She surveyed communities across Georgia engaged in various leadership programming. Participants were asked to identify how much they agreed or disagreed with statements such as, “Today, I believe my community is well-diversified in terms of multiple employers and stable employment.” She then asked participants if the statement was true five years ago (before participants engaged in leadership programming).

By comparing differences in capitals across time, Borron is able to evaluate programming effectiveness. The data also forms a comprehensive, unique profile for each community. It helps Borron identify which capitals are strengths and weaknesses in a community.

“Abigail has played a key role in strengthening our research-evaluation efforts,” said Carolina Darbisi, a Fanning Institute faculty member who worked closely with Borron to survey communities. “She is helping us develop tools to better quantify the social and economic impact of our leadership development programming.”

Borron plans to increase the flexibility of the framework to make it adaptable across Public Service and Outreach units. Her efforts have helped to better link the positive impact leadership development programming has on economic vitality, critical challenges and perceived strength of communities across Georgia.

“We know that leadership development is essential to the long-term civic and economic health of communities,” said Matt Bishop, director of the Fanning Institute. “However, the ability to quantify that economic impact and return on investment is key.”

Jon Calabria

Jon Calabria, an associate professor in the College of Environment and Design, is helping coastal Georgia communities tackle ecological problems, like shoreline erosion, that threaten their survival.

“We are trying to understand better ways to address some of the environmental issues that are becoming more prevalent,” Calabria said. “If we can use scientific-based information to solve some of these ecological issues, the benefit is the safety and welfare of the public.”

Shoreline erosion is a growing concern on the Georgia coast, where much of the economy depends on tourism and recreation. It can cause irreversible damage to cultural treasures like the Wormsloe Historic Site near Savannah, where Calabria installed living shorelines in strategic, highly targeted parts of the coastline.

“Living shorelines are effective because they offer protection from erosion, habitat for more animals, and visually look better than alternative methods like bulkheads,” he said.

In a living shoreline, plants and oyster bags are used as buffers between the land and sea. This type of solution helps keep habitat for native plants and animals, who are often displaced when bulkheads, or reinforced walls, are constructed. Calabria’s research is on the effectiveness and placement of living shorelines.

“Jon approaches projects from a landscape ecologist standpoint,” said Mark Risse, director of Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant. “He can understand the history and ecological setting of an area, and design solutions that fit aesthetically and contextually.”

In addition to Wormsloe, Calabria is helping Fort Pulaski and UGA facilities on Skidaway Island develop long-term plans to ensure for the safety, prosperity and longevity of their facilities.

Two of Calabria’s graduate students, Catherine Sauer and Christopher Wisener, are working with Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant faculty to gather data on living shoreline effectiveness and perceptions of the technique among Tybee Island residents. The information is part of their master’s theses.

“Jon was aware of our faculty and staff, and how they could contribute to students’ success. That to me is another outgrowth of the fellowship program,” said Risse. “We are able to help faculty and students help us, in a collaborative relationship.”

Elizabeth Weeks

Elizabeth Weeks, J. Alton Hosch Professor in the School of Law, worked with the Carl Vinson Institute of Government to identify rural health challenges relating to regulations and provider shortages in rural Georgia.

“Some rural communities don’t have access to necessary services like emergency services and obstetricians. That was my initial interest,” said Weeks. “As I’ve been here, it’s expanded to a variety of issues. If rural communities are losing hospitals, are there other ways to receive a necessary service?”

Weeks began looking into the effectiveness and feasibility of alternative health strategies proposed by Georgia legislators, such as telemedicine. Telemedicine is the ability to call a physician or specialist to receive services. Since telemedicine depends on broadband access, Weeks studied existing broadband access data collected by experts at the Vinson Institute. She discovered that nuances in the way broadband access is reported have a tendency to overestimate the number of people with broadband access.

Moving forward, Weeks plans to identify public health issues that local governments face, such as evolving federal regulations and shifts in Medicaid and Medicare. She will share what she learns with faculty at the Vinson Institute, who can use the information to help communities in Georgia.

Weeks’ interest was inspired by her father, Julien Devereux Weeks, a longtime faculty member at the Vinson Institute.

“That public service and outreach mission of a land-grant is very near to my heart,” Weeks said.

Weeks was a psychiatric social worker in Chicago before earning her law degree at UGA. She has become a nationally recognized resource on health law, health care financing and regulation, and public health law. Her focus is now on rural communities in Georgia.

“Elizabeth is a national health care law expert,” said Ted Baggett, Vinson Institute associate director. “A big concern right now is access to health care, quality of health care, affordability of health care, especially in rural areas. She’s a huge benefit to the faculty here.”