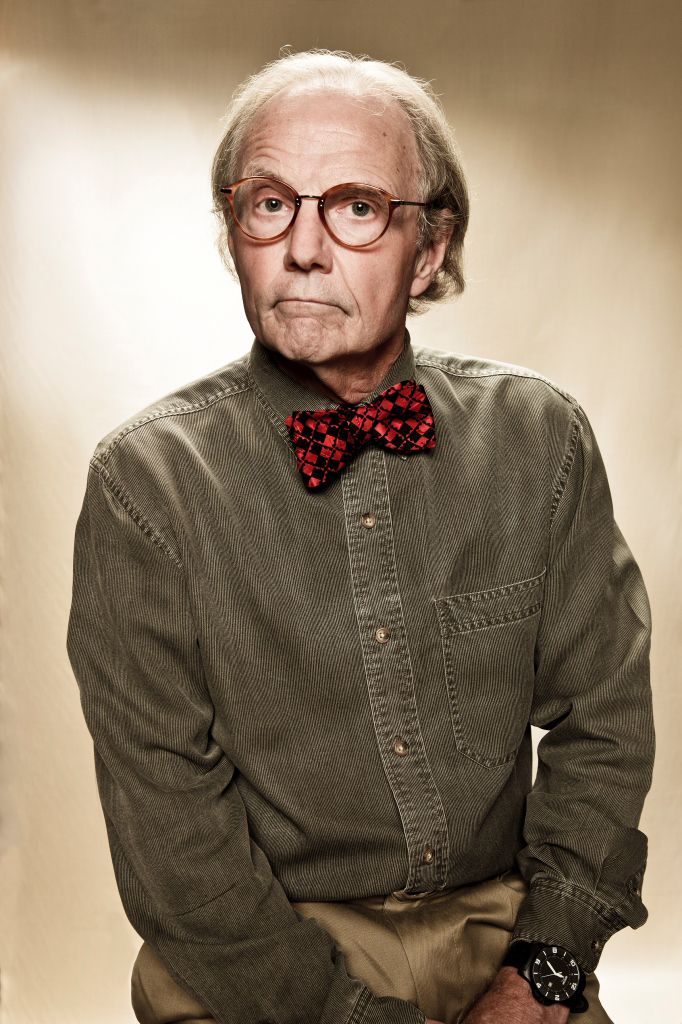

James Cobb, Spalding Distinguished Professor of History, teaches courses in Southern history and culture. A former president of the Southern Historical Association, Cobb has written widely on the interaction between economy, society and culture in the American South. He will autograph copies of his latest book, Away Down South: A History of Southern Identity (Oxford University Press) Sept. 29 at Barnes&Noble. He talks with Columns about his new book and images of the South.

Columns: Why did you write this book?

Cobb: Over my career, I’ve been really interested in the factors that set the South apart from the rest of the country. I began to realize early on that the whole matter was a lot more complicated than simply the South holding out against the rest of the country’s more-modern or progressive ideas. I did a book a few years ago about the Delta and how it got a separate identity. So I thought what I’d do now is take what I learned about the Delta and apply it to the entire South.

Columns: What was the biggest surprise you found while researching this book?

Cobb: Certainly one was the historical depth of black Southerners’ attachment to the South. I found astonishing evidence even going back into the 19th century, when things were about as bad as you’d think they could get for black people in the South, of black people holding on to their sense of roots as Southerners.

Columns: How has Southern culture changed over the past half century?

Cobb: I believe that cultures survive not by resisting change but by adapting to it. That’s probably the secret of why the South is seen by so many people as still very different from the rest of the country. But the biggest change, of course, has been getting away from the central focus on race as the essence of the Southern way of life-with segregation and Jim Crow being symbols. Since that time, both black and white Southerners have been able to explore what it means to be Southern in ways they couldn’t before because the race issue was there so fundamentally. There also have been changes in which economic events have thrust Southerners into suburban metropolitan environments and taken them away from the land and some of the places their identity is seen as being rooted. This has raised the question of whether Southern identity would even survive, but this seems to have prompted both black and white Southerners to be a lot more concerned with hanging on to and preserving their identity as Southerners.

Columns: Has the rest of the country held on to stereotypes about the South?

Cobb: Oh, absolutely. One of the big themes of my book is not just how Southerners see themselves but how the South has served the rest of the country as a kind of negative self-image. Even at the end of the Colonial period, there was a need for a kind of anti-America. Our enemies and our former Mother Country were gone, so we needed something to contrast ourselves with. That’s always part of the process of creating an identity. So the South was cast up as part of America but very un-American in some aspects, and that persists in a lot of ways even today.

Columns: Is the South still in the Civil Rights era or has it passed that?

Cobb: If any part of nation is, the South is. The fact is that the South has made, relatively, much progress. It represents the most physically, politically and institutionally integrated part of the country. Metropolitan areas like Atlanta are considered to be the land of economic opportunity for black people, and black people are moving to the South in far greater numbers than to any other region. So the focus is still on the South’s racial problems, and they certainly still exist, but I think there’s a growing realization that the South is not a battleground anymore. In fact, there are bigger battlegrounds outside the South.