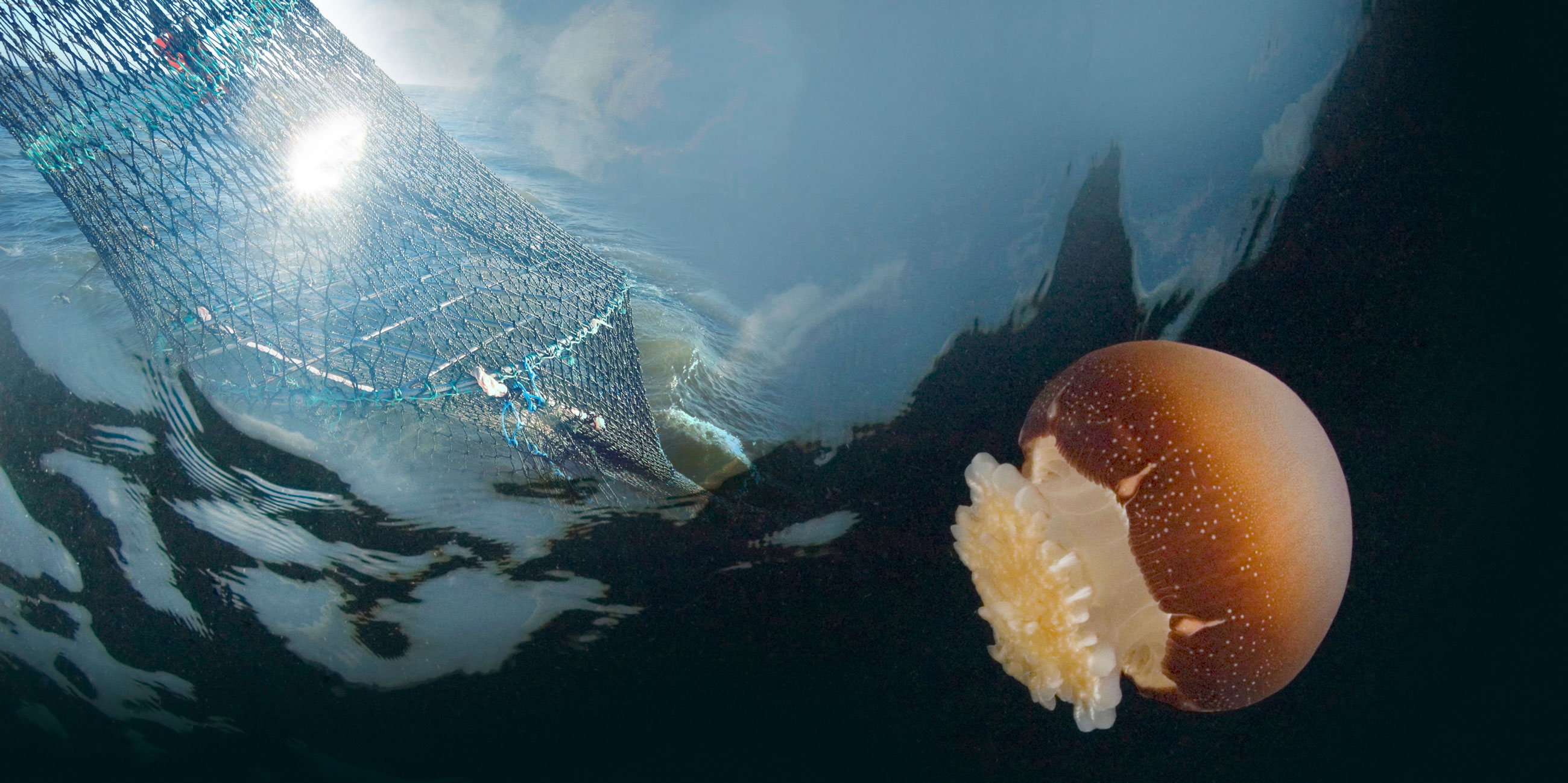

Savannah, Ga. — A Georgia Sea Grant-funded project will help protect turtles and enable fishermen trawling for cannonball jellyfish to operate more efficiently.

Georgia fishermen recently conducted several 30-hour cannonball jellyfish trawling trips to test the turtle excluder device, which is similar to the TED for shrimpers first developed in 1968.

Cannonball jellyfish, commonly referred to as jellyballs, are the third largest seafood commodity by weight in Georgia. Considered a delicacy in Asian countries, most of the jellyballs caught by Georgia fishermen are exported to Asian markets, where they’re sold in restaurants and grocery stores.

The project to develop a jellyfish TED was proposed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, the College of Coastal Georgia, and Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant at the University of Georgia, all of whom recognized the benefits of the commodity to both commercial fishermen and the economy.

“This was a project where we needed to support a developing industry,” said Mark Risse, director of Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant. “We have to protect our turtle populations, but also need to find a way to support our fishing industries. Much like the shrimping industry and TEDs, we are hoping to find a win-win solution.”

The jellyball industry emerged in the late 1990s but only has been recognized as an official industry in the state since 2013.

Shrimpers have been required by the federal government to use TEDs since 1987.

However, the TED required of shrimpers doesn’t work well with jellyballs because the 4-inch opening that prevents turtles from getting into the net is also too small for the jellies.

This requirement is seen as a hindrance to Howell Boone, a commercial fisherman who expressed concern over the impact of the current TED on his jellyball harvest.

“We can’t make any money using it … zero,” said Boone, who captains a commercial fishing boat that trawls for the jellies.

The team first tested Boone’s argument that the shrimp TEDs were ineffective for jellyball trawlers by pulling two identical nets behind his boat. One net was equipped with a certified TED; the other had no TED. Results of the trawl showed that nets with certified TEDs caught 23.6 percent fewer jellyballs by weight, when compared to a net with no TED, which supported Boone’s concerns about the TED limiting catch.

The next step involved designing a practical TED for the jellyfish industry that would appease fishermen, state resource managers and biologists.

“We’ve been involved with TED development and certification since it began in the late 1970s,” said Lindsey Parker, a marine resource specialist at Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant.

“We are familiar with how government agencies evaluate TEDs. We know the tasks it will have to perform and how well it needs to perform those tasks when put to the test.”

Parker, who has a 35-year history with Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, worked with Howell Boone’s father, Sinkey Boone, who invented the first turtle excluder device. The original design has been modified over the years to be more efficient and eventually gained national certification in 2012.

The new jellyball TED, designed by Howell Boone, has an 8-inch opening, large enough to let 6- to 8-inch jellyballs into the net but small enough to keep sea turtles out.

The team conducted 22 paired trawls using the same methods as before, but yielding much different results. There was no significant difference in the amount of jellyfish caught between the net with the experimental TED and the net with no TED.

Patrick Geer, chief of Marine Fisheries for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and co-principal investigator on the jellyball TED project, said the new design looks promising and could be considered for use in state waters.

“If we can use the results of this study to support and manage this emerging fishery in an ecologically responsible manner that not only helps the economy but supports commercial fishers then it’s our responsibility to do so,” Geer said.