A trio of University of Georgia engineering students have found a way to maintain the Fort Pulaski National Monument site as a viable destination for park visitors for the foreseeable future.

Sea level rise, severe storms and more frequent flooding have made it difficult for the wastewater in the park’s septic drain fields to filter out through the soil.

“That could mean contaminated water is rising up onto the ground, and that’s not safe for humans or the environment in general,” said Sarah Pierce, a recently graduated senior who worked on the project.

Without a way to safely remove the waste, the park would not be able to continue welcoming the more than 350,000 guests who visit the National Park Service’s Civil War battle site each year. Currently, there are only six functioning toilets and two functioning urinals on the property.

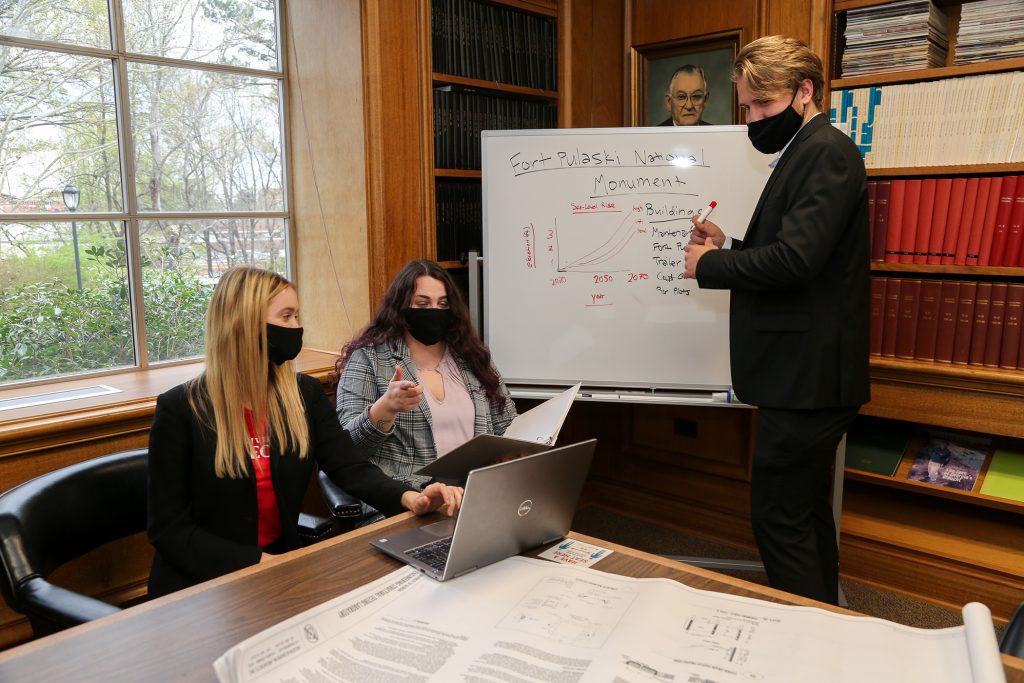

Pierce and fellow College of Engineering seniors Emily Mitchell and Sawyer Soucie spent the past year working with UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant on a senior capstone project to develop a sustainable solution that would be resilient to changing water levels and not harm the protected marshlands that make up the majority of the park.

The team studied the infrastructure on Cockspur Island, where the park and a U.S. Coast Guard station are located, looking at sea level rise projections, soil composition and wastewater volume. They ultimately proposed three ideas: building an improved, mounded septic system; developing a mini wastewater treatment plant on Cockspur Island; and installing a network of pipes to transport the wastewater to the municipal wastewater treatment facility on neighboring Tybee Island.

The piping option was the clear choice. While all three proposals would solve the park’s issues in the short term, piping the wastewater off the island was the only solution that could permanently eliminate the need for the 13 septic systems on the island, including those used by the Coast Guard.

“Environmentally it’s safest for the long term,” said Mark Risse, director of Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant and a mentor to the engineering students on the project. “On a barrier island with sandy soil and increasingly high-water tables, [septic systems] are just less and less effective and more and more likely to cause environmental degradation.”

The big question was whether the City of Tybee Island, which is facing some of the same challenges with rising sea levels, would be willing to take on the additional waste from the fort. But city officials recognized that protecting the national monument would benefit the entire region, which relies heavily on tourism as a local revenue source. The students’ designs for the pipeline included the possibility of tying in waste from restaurants and retail shops on the outskirts of Tybee Island, which could soon face the same issues with their septic service.

“We were really being baptized by fire,” Soucie said of the project. “It’s more than just designing a septic system or a wastewater system. It’s about all these moving parts and trying to get them moving in the right direction. It’s been a lot of learning, which is exciting.”

The students virtually showcased their final presentation to Fort Pulaski administrators, Tybee Island officials and representatives from both the U.S. National Park Service and Coast Guard at the end of the spring semester.

Fort Pulaski Superintendent Melissa Memory, herself a 1989 graduate from the Department of Anthropology at UGA, was thrilled by the quality of the students’ work.

“They’ve blown it out of the water metaphorically and literally with how far they’ve taken this project,” said Memory. “A lot of student projects are good at concepts, but it’s rare that they get it this far and give us a clear direction on path forward. …They far exceeded our expectations for what they’d be able to do for us.”

Consultants are already working on pipeline designs and concepts based on the students’ presentation, which represents significant savings for the fort. Memory and U.S. Park Service officials are exploring ways to finance the project.

For the students, the project provided an opportunity to put their academic education to the test in the real world.

“This is a huge passion of mine,” Mitchell said. “Water quality engineering specifically. I’ll be pursuing this in the future, and this is a major steppingstone in my career. I’m just extremely grateful to be on such an incredible project like this, especially with so many stakeholders and importance of everyone involved.”

The demand for coastal engineering will only increase in the years to come. The students’ efforts — both in engineering and politics — is a showcase for how communities need to work together to combat the growing effects of sea level rise, said Brian Bledsoe, director of the College of Engineering’s Institute for Resilient Infrastructure Systems, who mentored the students on the Fort Pulaski project.

“Fort Pulaski is not the only park or monument that’s grappling with having to adapt to climate change and sea level rise and a rapidly changing world,” Bledsoe said. “I think this could be a good example of how partnerships with adjacent communities can work. When we share infrastructure, we can keep our options open and maybe find more long-term and cost-effective solutions. Hopefully this is something that the park service can hold up as an example of what other entities can do.”