Multilingual students face unique challenges that can hurt their performance in school. New methods of teaching may help close this gap, according to a new study from the University of Georgia.

In the United States, English is the main language used in classrooms. Schools also tend to rely on spoken communication to teach and written exams to assess learning.

That can make it difficult for multilingual students to express themselves. This is especially true in science classes, with their specific terms and complex sentence structures.

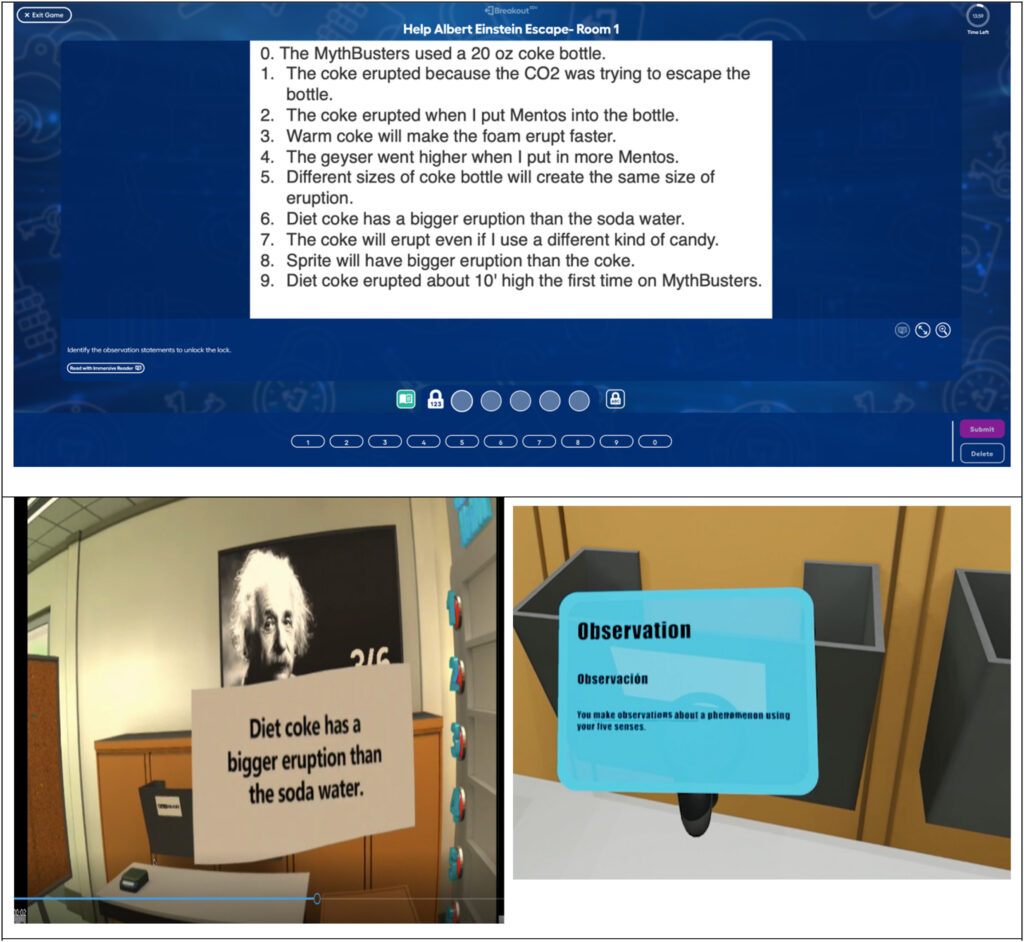

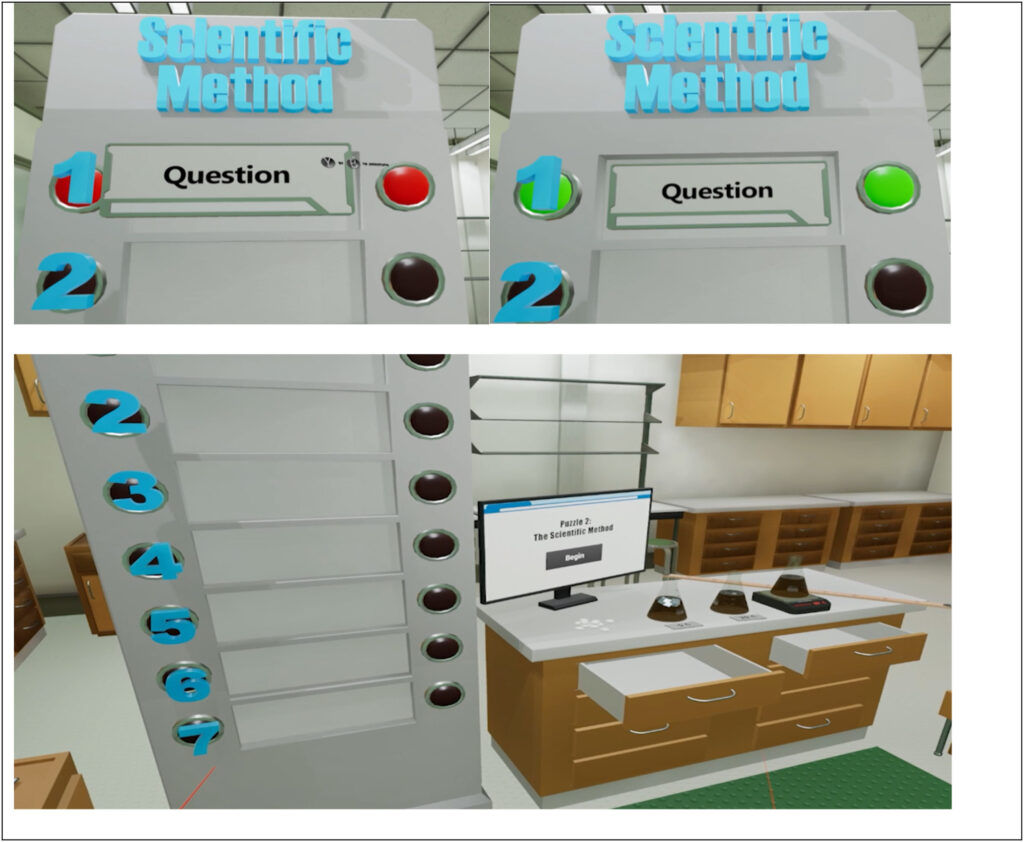

So a UGA researcher developed an immersive virtual reality game to communicate scientific concepts to students in new ways.

Students were tested before and after they played the game either on a desktop or through immersive virtual reality, with researchers comparing their scores to see whether the game helped the students better grasp the material.

All the students’ scores improved after playing the game, and multilingual students performed as well as their English-speaking peers.

Visual cues, body movements provide alternate ways to learn concepts

The virtual reality game used visual, audio and body movements to give students multiple ways to learn and express their knowledge on a subject. Researchers referred to this as multimodal meaning-making, or using several ways of communicating to process and convey information.

The study suggests that being able to construct meaning from multiple methods is critical for multilingual students.

“Virtual reality offers meaning-making processes or meaning-making opportunities that go beyond just verbal communications,” said Ai-Chu Elisha Ding, lead author of the study and an assistant professor in UGA’s Mary Frances Early College of Education.

“Multilingual learners performed pretty well because they got the support they needed, and they had different ways to express their understanding beyond the typical ways that they did in the science classroom.”

Multilingual students could benefit from multiple ways of communicating

Outside of the classroom, people use more than their words to communicate. Hand gestures, facial expressions and body language all impart their own meaning in interactions.

These nonverbal cues are often overlooked in schools.

“In the U.S. education system, students mainly communicate their ideas through English,” said Ding. “Classroom interactions are also very verbal, meaning that students and teachers express themselves through written language or orally. That creates a lot of barriers for multilingual learners.”

Virtual reality can help overcome those barriers by helping to communicate ideas visually rather than just through words.

Virtual reality can add nonverbal cues to lessons

The lead researcher and her colleagues worked with a middle school science teacher and English as New Language teacher to develop a virtual reality game featuring content taught in the science classes. The game and the lessons are designed to help students learn science and develop their language skills at the same time. The study included 97 seventh grade students in an urban middle school in Indiana.

The researchers developed the game into two modes: one on a virtual reality headset and one on a desktop computer.

The game with the headset focused on visual and audio cues to give feedback and allowed students to interact with the virtual environment around them. The desktop game relied more on text to convey information and was designed to be less immersive.

One of the key takeaways of the study is that teachers should pay close attention to using visuals and hand gestures to help students process information.” —Ai-Chu Elisha Ding, College of Education

Students were then tested on their knowledge of the material covered in the games, how they made connections between the concepts introduced and how they translated their thoughts into writing.

All students saw an improvement in their test scores. Multilingual students also performed just as well as students who only spoke English. Additionally, students who played the immersive VR game improved their test scores significantly more than the students who played the desktop game.

Observation is critical in science, and the virtual reality game put the students in an environment where they could study a topic in an immersive way, according to the researchers. The desktop mode couldn’t provide the same kind of experience, explaining why those students didn’t perform as well.

While virtual reality games aren’t available in every classroom, Ding emphasized that students can still benefit from teachers branching out into new teaching methods.

“Teachers can do a lot of different things to make this kind of nonverbal-based communications happen more in the classrooms,” Ding said. “One of the key takeaways of the study is that teachers should pay close attention to using visuals and hand gestures to help students process information.”

This study was published in Learning and Instruction and co-authored by Eunkyoung Elaine Cha, a doctoral student of UGA’s Department of Workforce Education and Instructional Technology. The study was funded by Ball State University through the Creative Teaching Grant.