For Peter C. Doherty, the only veterinarian thus far who has been awarded the Nobel Prize, the second best aspect of conducting research is telling others about it.

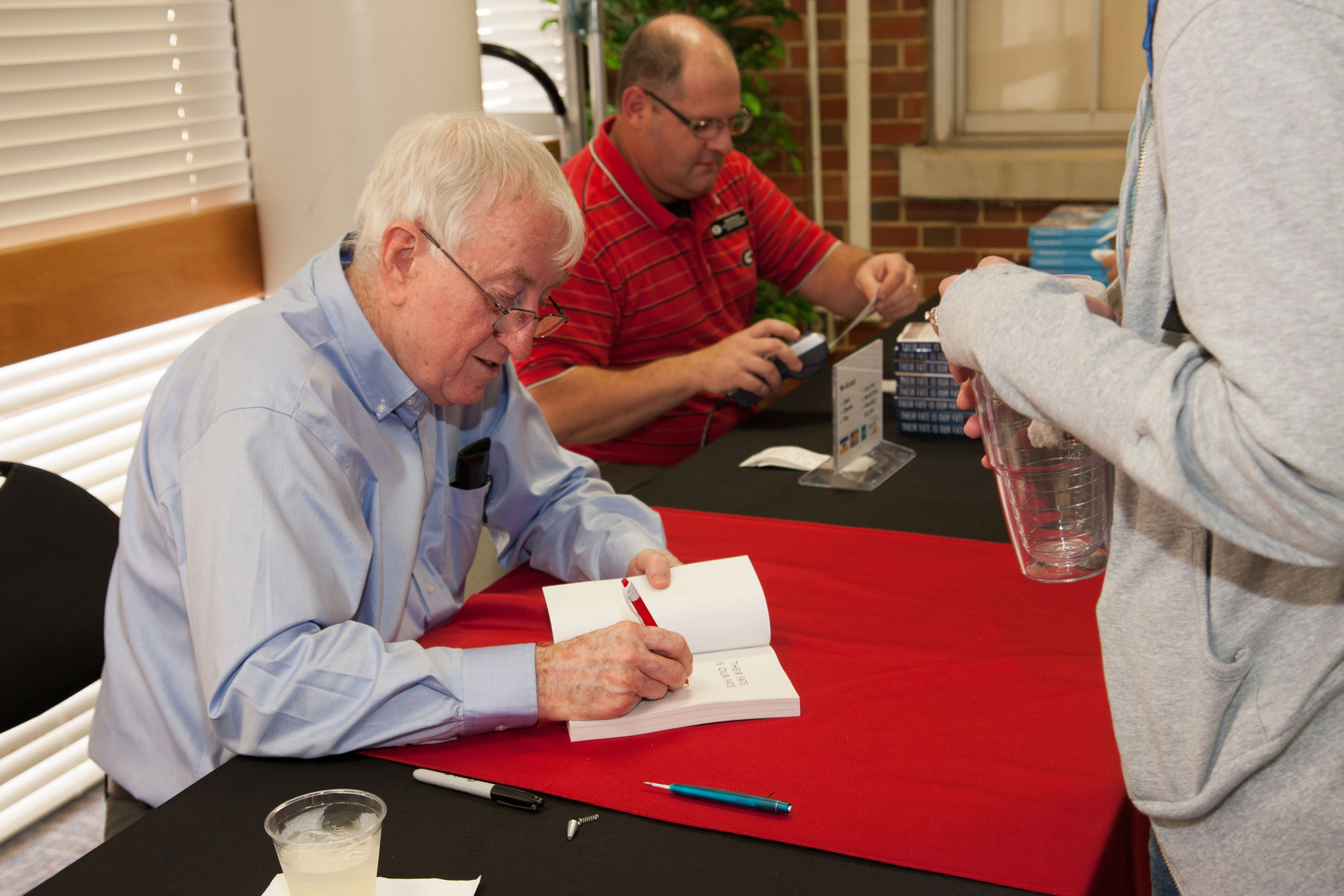

Doherty believes the lay public needs a better understanding of science, and that “citizen scientists” play an important role in the scientific community. He shared these ideas, including the concept of “One Health,” which is the interconnectivity of human public health, animals and the environment, and discussed his two latest books—Their Fate is Our Fate: How Birds Foretell Threats to Our Health and Our World and Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know—Sept. 10 with an audience of more than 400 at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

“What’s emerging is this citizen action to monitor the environment,” he said. “These are groups who watch birds, beaches, rivers and more. When organized properly to collect data, this citizen science is getting more people involved with the business of science.”

In 1972 Doherty became a research fellow at John Curtin School of Medical Research in Australia. There he met a medical doctor from Switzerland, Rolf Zinkernagel, who had similar research interests. Together, they discovered how T cells recognize virus-infected cells by looking for variants in certain molecules, called histocompatibility antigens, on the surface of infected cells. Their study, considered controversial at first, was published in a 1974 issue of the journal Nature. In 1996, they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

With a research focus on avian influenza, Doherty began to see the connections between the environment and pandemic illnesses in humans. His latest book about pandemics uses a question-and-answer format to help readers understand various immunology topics.

“Hundreds of infections can kill you in a ghastly way, but you don’t have to worry as much about organisms that spread to us from bats, birds, pigs or mice because these typically don’t transmit from one person to the next,” he said. “What we have to watch very carefully are the infections that come to us from other species, yet can also spread among humans.”

Doherty mentioned the current outbreak of H7N9 in birds in China. Though it only caused a mild infection in birds earlier this year, as of mid-August, the World Health Organization reported 135 laboratory-confirmed human cases, including 44 deaths. The global spread of H1N1 in 2009-the fastest spreading flu virus to date-bolstered Doherty’s belief in the importance of explaining scientific topics to nonscientists and involving them in the discussion about pandemics.

“What’s happening in science right now is enormously important, and we need people to engage with what’s happening in the environment and climate change,” he said. “Many aspects of geology, biology, meteorology and others are related, and to understand what’s happening in the world, you need some familiarity with the science.”

In Their Fate is Our Fate, Doherty uses a narrative approach to explain how the habits and movements of birds explain changes in the environment-and how nonscientists can become aware of the changes in their own backyard. When a bird population drops by half, it’s likely due to overfishing in the area or commercial development that leads to habitat loss, he said.

“Birds tell us about ourselves and our infections and how the world is changing,” he said. “Several stories in the book show how our impact on the environment can result in long-term destruction of species.”

Doherty spoke about the importance of speaking to politicians about science and supporting public funding for scientific research related to the environment. It’s a challenge to buck misconceptions and misunderstandings, but ultimately politicians listen to votes, he said.

“That’s why we need a scientifically literate population, and this is especially important for those sitting on boards and committees involved with local issues,” he said. “If you see a good science story, put it on Facebook or tweet it. Communicating science is an important function for all of us.”

Since 1988, Doherty has been on faculty at the Department of Immunology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, where he holds the Michael F. Tamer Chair of Biomedical Research. He divides his time between Memphis and Australia, where he is a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Melbourne Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences.