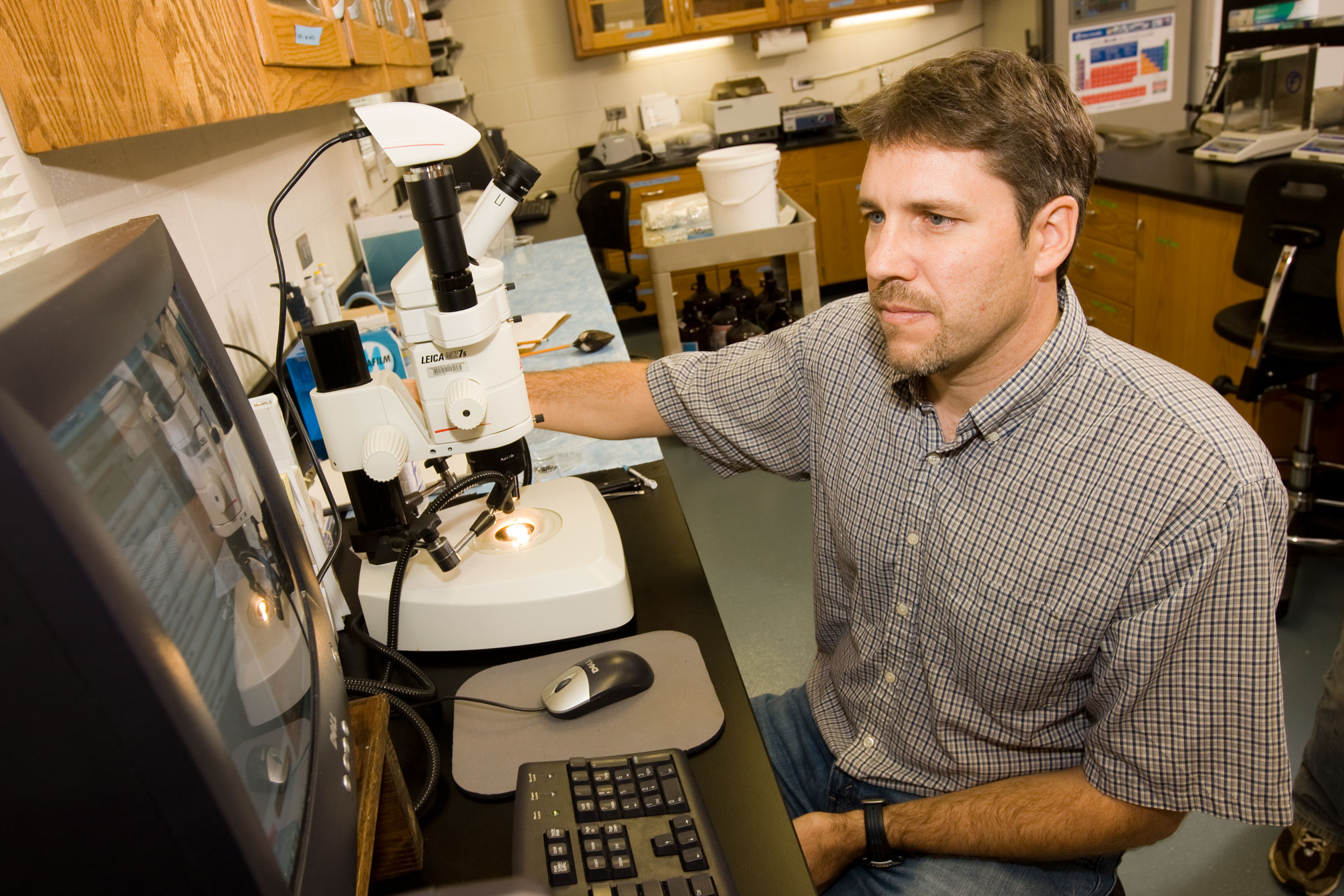

There may be a lot of fish in the sea, but Robert Bringolf is looking for just one.

The Warnell assistant professor is hot on the trail for what he’s calling “the missing link,” a specific species of fish that is crucial to the survival of the Altamaha spinymussel, one of more than 120 species of mussels essential to cleansing Georgia’s waters. Identifying that fish, according to Bringolf, has proven to be quite a mystery so far.

“It’s a much bigger issue than saving a few mussel species. Freshwater mussels are like canaries in coal mines,” he said. “They’re long lived animals that survive by filtering the water, up to 30 gallons per day per mussel. If something is wrong with the river, the mussels will tell us.”

Since joining Warnell’s faculty in 2007, Bringolf has largely focused his research efforts on mussels and is now narrowed in on the mysterious spinymussel, which is at risk of disappearing entirely from Georgia’s waters. Found only in the state’s Altamaha River, the spinymussel will soon be classified as an endangered species. There are many unanswered questions about spinymussels, like how they reproduce and complete their lifecycle.

That’s where Bringolf comes in. The Iowa native has a grant from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to find out how the spinymussel reproduces, which is critical to saving it from extinction. Mussels, according to Bringolf, have larvae that must attach to a fish’s gills to successfully transform into juvenile mussels. Unfortunately, not just any fish will do.

Many mussels require specific fish species. Although biologists have figured out which fish species are needed by about half of Georgia’s 122 kinds of mussels, the spinymussel isn’t one of them. Bringolf is hopeful that the two-year project will succeed in answering not only those questions, but also puzzles about other Altamaha mussels like the threatened Altamaha arcmussel.

Little is known about the creatures, according to Bringolf, so scientists are trying to figure out how drought, land use, pesticides and sedimentation affect them. Mussels play an important role by filtering algae, toxins and other impurities from water, making their presence crucial to cleansing lakes, rivers and streams.

“There is no single ‘smoking gun’ when it comes to the disappearance of most mussel species,” said Bringolf, who is also a Lilly Teaching Fellow. “It’s probably death by a thousand cuts in large rivers like the Altamaha.”

Bringolf is the author or co-author of more than a dozen publications. His research generally focuses on understanding the effects of chemicals and other stressors on fish and mussels.

In the case of the spinymussel, identifying the fish species needed for reproduction may allow laboratory culture of this rare species for restocking in the Altamaha or for studying its sensitivity to contaminants.

Spinymussels aren’t taking up all of Bringolf’s time at Warnell. He is part of a team receiving DNR funding to study the reproductive biology of tripletail (fish) off Jekyll Island. He is also funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to study the effects that contaminants are having on the ability of mussel larvae to attach to fish and transform into juveniles.

Bringolf teaches courses in eco-toxicology, fish physiology, aquaculture and conservation of natural resources.

“I feel very blessed to be able to do what I love and get paid for it,” he said. “War