Photographer Doris Ulmann documented rural Southern people, and in a new exhibition attempts to cast light on this lesser-known artist. “Vernacular Modernism: The Photography of Doris Ulmann,” opens Aug. 25 at the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia and runs through Nov. 18. Organized by the museum’s curator of American art, Sarah Kate Gillespie, it is the first complete retrospective of Ulmann’s work.

Ulmann self-identified with the pictorialist movement, though her work does not adhere to many of the principles associated with that style. In addition, she was labeled both as amateur and professional, as she did not rely on photography to make her living but was a recognized photographer in the 1920s and 1930s.

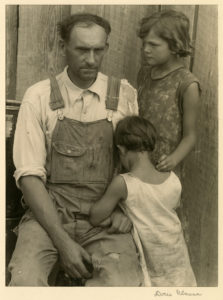

A photograph by Doris Ulmann (American, 1882–1934), “Cheever Meaders and Daughters, Meaders Pottery, Cleveland, GA,” ca. 1933. Posthumous gelatin silver print, printed by Samuel Lifshey, ca. 1934–37, 8 x 6 inches. Berea College and the Doris Ulmann Foundation, 3257.

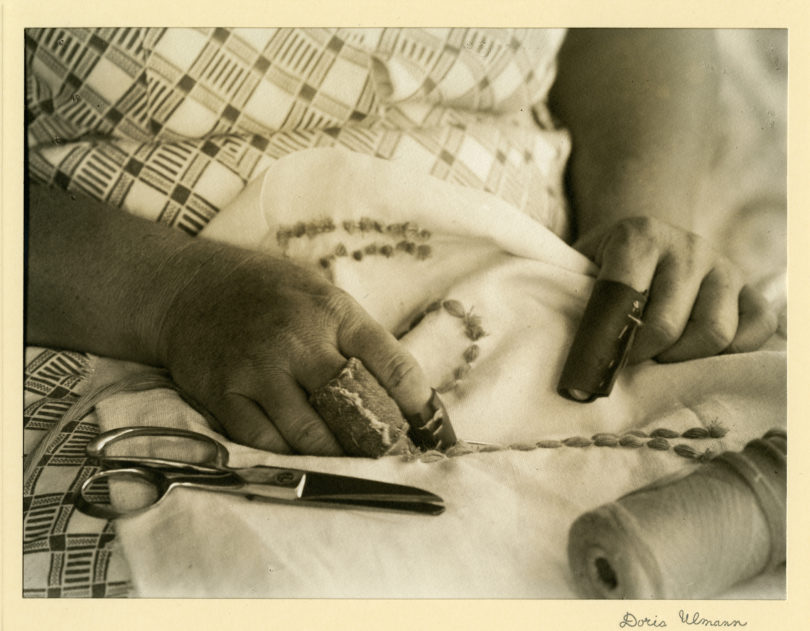

Her images have elements of pictorialism (fine art photography that often blurred its subjects to emphasize atmosphere) and documentary photography, two strains not usually linked. At the same time, it has some overlap with the concerns of modernism: a priority on form and sharp tonal contrast and quality of line. Like the American regionalist artists, Ulmann also maintained a strong interest in the idea of a “usable past,” a shared American culture that continued to shape the present.

In some ways, her body of work can be divided in half: those portraits done of sitters in her Upper East Side apartment-turned-studio, and those created on the road and on location in rural areas such as Appalachia, Louisiana and South Carolina. Ulmann liked to create multiple exposures of her sitters in different poses or environments in an attempt to showcase their true nature, whether they were New York writers, Appalachian weavers or medical faculty. In 1933, she collaborated with author Julia Peterkin on “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” a book of photographs and essays on rural southern African Americans, including many Gullah people. The project predated many later combinations of portrait photography and essays focusing on rural people, like “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.”

Photograph by Doris Ulmann (American, 1882–1934), “Member of the Order of Sisters of the Holy Family and Child (Probably a Student), New Orleans, LA,” December 1931. Posthumous gelatin silver print, printed by Samuel Lifshey, ca. 1934–37, 8 x 6 inches. Berea College and the Doris Ulmann Foundation, 3406.

One common thread in her work is Ulmann’s desire to portray the personality and experience of each sitter. In the foreword for her second book of portraits, “A Book of Portraits of the Faculty of the Medical Department of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore,” Ulmann wrote that her idea was to make portraits that “grasp enough of the dominant character and outstanding personality of the individual to make verbal delineation superfluous. … In these portraits the aim has been to express as much as possible of the individuality and character of each member of the faculty.” She also made special efforts to photograph professional women and African Americans throughout her career, an unusual tendency at the time.

Gillespie has been studying Ulmann’s work since before she took her current position at the university, four years ago, and she is excited to share her enthusiasm for it. “Ulmann is an understudied and important photographer, and I am thrilled that the Georgia Museum of Art is showcasing her work in such an extensive manner,” she said. “I think visitors will be surprised by the variety and depth of her photography.”

The exhibition will consist of about 100 photographs by Ulmann as well as related books, crafts and works of art by some of her contemporaries. Additionally, the museum will publish a 200-page hardcover book by Gillespie that includes an analysis of Ulmann’s photography from her early work up until her premature death. It will be available for purchase in the Museum Shop, from Avid Bookshop or online from Amazon.com.

The exhibition, publication and related programs are sponsored by the Henry Luce Foundation, the LUBO Fund Inc., the Southern Humanities Fund, the W. Newton Morris Charitable Foundation and the Friends of the Georgia Museum of Art.

Related events include:

- Family Day on Sept. 8 from 10 a.m. to noon

- Toddler Tuesday on Sept. 18 at 10 a.m. (register via sagekincaid@uga.edu or 706-542-0448)

- Public tours with Gillespie on Sept. 26 and Oct. 17 at 2 p.m.

- A screening of the film “A Lasting Thing for the World: The Photography of Doris Ulmann” on Oct. 4 at 7 p.m.

- A screening of “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” on Oct. 11 at 7 p.m.

- A talk by Ellen Handy, associate professor of art history at City College of New York and specialist in 19th- and 20th-century photography, on Oct. 12 at 3 p.m.

- 90 Carlton: Autumn, the museum’s quarterly reception ($5, free for museum members) on Oct.19 at 5:30 p.m.

- A program of choral and instrumental pieces from Appalachia by Athens Chamber Singers on Nov. 4 at 2 p.m.

- A lecture by writer and public historian Elizabeth Catte on Nov. 8 at 5:30 p.m.

- And a Teen Studio on Nov. 8 from 5:30 to 8:30 p.m. (email sagekincaid@uga.edu or call 706-542-8863 to reserve a spot).

All programs are free and open to the public unless otherwise indicated.