Chris Reisch has come full circle. Five years ago, as an undergraduate and then a graduate student, he was part of a UGA research group that identified the first step in the pathway by which bacterioplankton control how much sulfur is released into the ocean’s food web. Science published that study in 2006.

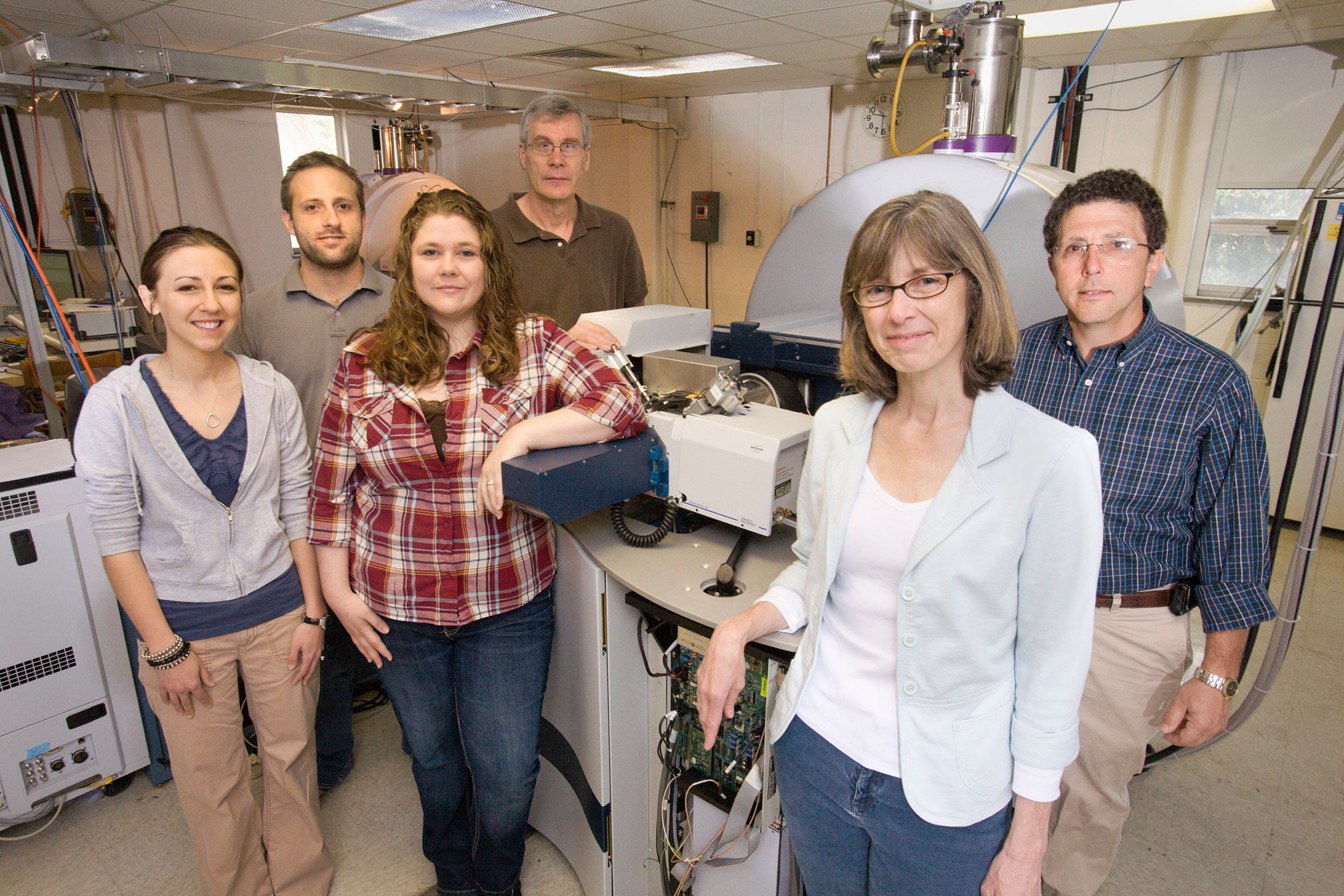

Earlier this month, Reisch-now a graduate student working with Barny Whitman and Mary Ann Moran, Distinguished Research Professors from microbiology and marine sciences, respectively, and other UGA collaborators published a Nature paper, this one elucidating the rest of the pathway and identifying the genes responsible for the process. The paper adds an important piece to the sulfur cycle puzzle.

“With our increased understanding of the sulfur cycle in the ocean, we are now better able to evaluate the potential for manipulation as has been proposed as a way to mitigate global warming,” said Whitman.

But, as Reisch is the first to point out, the discovery of the pathway would not have been made without chemistry graduate student Melissa Stoudemayer and department head Jon Amster.

“The answer is in front of you, but you have to know how to look at it,” said Reisch.

He had narrowed down the first intermediate in the process to three compounds, but which one? Whitman suggested high-resolution mass spectrometry might provide insight to the chemical structure of the compounds. So they turned to Amster, with whom Whitman had collaborated previously. Together, they were able to unambiguously identify the elusive compound as a Coenzyme A (CoA) derivative, a class of molecules with many roles in metabolism, as the missing piece in the pathway.

Once the team discovered the intermediates, everything fell into place: finding the enzymes that catalyzed the reaction, and then discovering the genes, and finally analyzing databases of marine bacteria to determine which bacteria possess the genes capable of releasing sulfur into the food web. In fact, once they knew how to look, they realized that Vanessa Varlajay, also a graduate student in microbiology, already had made a mutation in one of the genes while working on a different aspect of the project.

The collaborators built on a line of research begun by Moran at UGA over a decade ago. Her early research showed that an abundant group of bacteria known as marine roseobacters play a role in taking dimethylsulfonioproprionate (DMSP), the chemical made by marine algae and released into the water upon their death, and moving it into the atmosphere as the compound dimethylsulfide (DMS).

In 2006, Moran’s research group discovered in marine bacteria the first step in the process of turning DMSP into MeSH, instead of sending sulfur into the atmosphere. And in 2008, Moran’s doctoral student Erinn Howard, in collaboration with Whitman’s lab, discovered the gene that allows marine roseobacters to keep sulfur in the ocean. Reisch was a part of the first group.

“The big mystery about bacteria is what they are doing in nature,” said Whitman. “The organisms metabolize compounds for their own needs. We need to understand what they are getting out of it to understand what it means for the ocean. Now it will be possible to look at the environmental importance of this process and how it’s regulated.”

“The group discovered that the MeSH pathway is widespread among bacterioplankton in the ocean,” said Reisch. “The genes may be in up to 61 percent of surface ocean bacterioplankton, while the DMS pathway is present in less than 5 percent, although there could be a lot more that we don’t yet know about. Some bacteria, including the model bacteria used in the study, have both pathways.”