(Originally published March 12, 2020)

(Originally published March 12, 2020)

The same science that can help poultry farmers raise more feed-efficient chickens could help people become healthier, too.

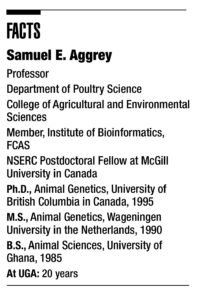

Sammy Aggrey, professor of poultry science at UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, studies the ways in which genes affect how chickens process feed. What he’s found has led to the development of more efficient broiler (meat) chickens, but his research also has implications in the fight against obesity in people.

Currently, Aggrey’s lab focuses on the nutrigenomics of poultry, investigating the genes that are responsible for processing the amino acids and other nutrients in chicken feed. Several genes affect the way birds digest carbohydrates, amino acids and fat. The metabolism of amino acids like methionine and cysteine affects the way the birds process antioxidants to battle stress and disease.

His lab also is investigating how feed and genetics impact the birds’ microbiome, parasite loads and gut health. Just like humans, poultry also suffer from leaky gut when the microbiome balance is disturbed. The microbiome also can possess certain genes that can confer resistance to antibiotics.

Generally, heat stress is costly to farmers as they reduce productivity and profitability. Heat stress also causes welfare and well-being issues for the chickens. However, Aggrey’s lab has established that heat stress also curtails the reproductive cycle of coccidian parasites in chickens.

Currently, nutrigenomics, microbiome and precision poultry are the focus of the Aggrey lab. The efficient use of water in poultry is an area that deserves lots of research attention. Meeting these specific breeding goals and understanding how genetics impacts the health and efficiency of birds has become increasingly possible in the last two decades thanks to a better understanding of chicken genetics and data science.

“We used to breed without a lot of information” Aggrey said. “When the genome was sequenced, the sequence provided us with unprecedented data to accurately determine the genetic worth of animals. That comes with a lot of computation.”

Using innovative computation techniques, including fuzzy logic, machine learning and artificial intelligence, neural networks have become part of identifying novel traits and breeding.

Due to changes in the climate, a shift to antibiotic-free production and the trend toward cage-free production for egg layers, Aggrey’s lab research into microbiome, resilience to the environment, partitioning of nutrients and host response to parasites helps produce adapted and robust chickens.

Meeting these specific breeding goals and understanding how genetics impacts the health and efficiency of birds has become increasingly possible in the last two decades thanks to a better understanding of chicken genetics and data science. To incorporate all of this new genetic information, Aggrey has had to collaborate with other geneticists to develop analytic tools to aid in better breeding.

“The era of ‘do it alone’ in science has passed,” said Aggrey.

He is closely collaborating with Romdhane Rekaya, a faculty member in the college’s animal and dairy science department, scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute in Kenya, Martin Wagner at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Austria and other scientists at Cairo University and the University of Ghana.