UGA researchers are not looking to pull sweet fruit from the papaya tree branches. They’re peering deeper to study its genes and see how they compare to other plants.

Researchers with the UGA Plant Genome Mapping Laboratory helped to write two articles involving the fruit as either the focus or a major player. One article appeared April 24 in Nature magazine, the other April 25 in Science.

“Two articles in consecutive days in journals like these makes for quite a week,” said Andrew Paterson, the lab’s director. He is also a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar with UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

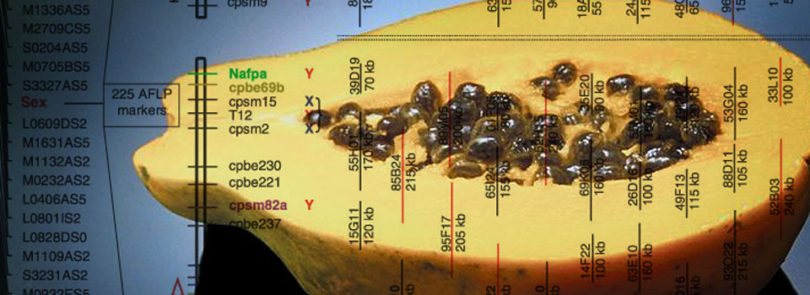

For the Nature article, Paterson and five scientists at the lab worked with an international team to sequence the papaya’s genes. The team was lead by Ray Ming, a professor at the University of Illinois and Paterson’s former post-doctoral student.

The papaya is the fifth angiosperm, or flowering plant, to have its genes completely sequenced and published. The others are Arabidopsis in 2000, rice in 2002 and grape and poplar in 2007.

Papaya is an agricultural crop in tropical climates. It ranks first in nutritional values among 38 common fruits, based on its vitamin and mineral content. It is the source of papain, an enzyme used in meat tenderizer and medical applications.

The researchers were surprised to find that papaya has fewer genes than the simple Arabidopsis, a small plant in the mustard family. Arabidopsis is commonly used to study plant genetics and genomics. The papaya also has sex chromosomes, a rarity in plants.

“Papaya turns out to be a promising botanical model,” Paterson said. “It’s potentially useful as a system to unravel which gene performs which function, and also useful in helping us tie together the genetic blueprints of all angiosperms.”

The papaya cultivar used for the study was one genetically modified to resist ringspot disease, a virus that almost wiped out papaya farming in Hawaii. It’s the first genetically modified plant to be so fully sequenced.

The article in Science magazine compares papaya’s gene strands with those of poplar, grape and Arabidopsis. UGA graduate student Haibao Tang was the lead author of that article. It explains how UGA researchers are building computer models to see how plants have changed from their ancestors to what they are today, said UGA scientist John Bowers.

By studying Arabidopsis, poplar, grape and papaya gene strands side by side, Paterson and other scientists are hoping to learn what certain genes do in these plants. This will allow them to make an educated guess about what the same gene does in cotton, for example.

The idea to do this kind of analysis has been around since the turn of the last century, Paterson said. But it wasn’t until the last year that there has been enough information to compare different plants on the whole-genome level.

And now the gene sequences are giving the UGA lab an opportunity to practice its research prowess to better understand all flowering plants, including most major crops.