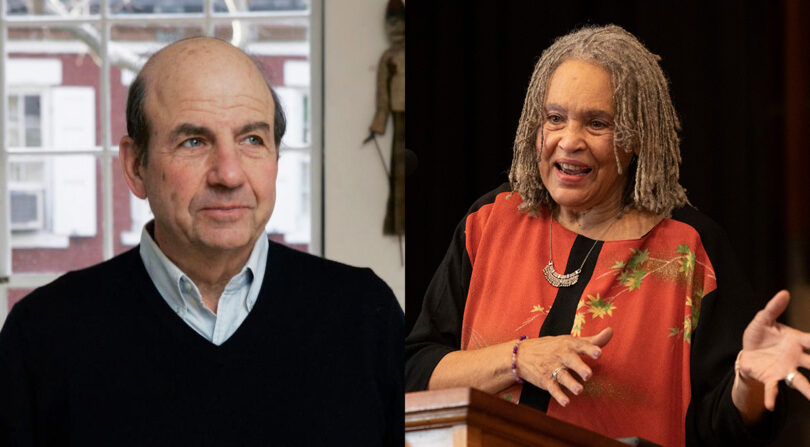

The bond between Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Calvin Trillin started 60 years ago.

Hunter-Gault, along with the late Hamilton Holmes, became the first African American students to attend the University of Georgia in January 1961. Trillin, a young journalist, covered their courageous first steps on campus for Time magazine.

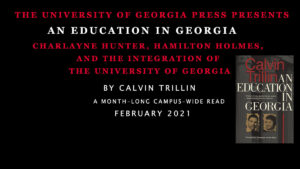

The pair reunited for a virtual conversation about Trillin’s book, “An Education in Georgia: Charlayne Hunter, Hamilton Holmes, and the Integration of the University of Georgia” (UGA Press), on Feb. 4. The event, which is part of a variety of events honoring the 60th anniversary of desegregation at UGA and designated a Signature Lecture, was moderated by Valerie Boyd, Charlayne Hunter-Gault Distinguished Writer in Residence and associate professor in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

Boyd read from the introduction Hunter-Gault wrote for Trillin’s book, who then spoke about how he built that sense of trust. On the day they met, Trillin stood out because he stood back, unobtrusively moving through the crowd that had gathered as Hunter-Gault went to her psychology class.

“I was very busy not paying attention to the ugliness around me but watching the journalists watch me,” Hunter-Gault said. “The yelling got to me. I didn’t like it because it seemed like some were more interested in their questions than my answers.”

A journalism lesson

She said that she began to learn about journalism from Trillin. In particular, she noticed that he was always watching.

“That’s what good journalists do—they observe,” said Hunter-Gault, who went on to become a Peabody and Emmy award-winning journalist and the author of four books.

For his part, Trillin, a longtime staff writer at The New Yorker, recognized that while those first steps were significant, the hard part was still to come.

“In those days, desegregation was a snapshot,” he said. “In a way, that was very brave for those people, but the brave part is the next two or three or four years. That should be written about.”

Trillin’s book was originally published in 1964, specifically so that he could come back to Georgia after Hunter-Gault and Holmes graduated. He said that their story was worthy of a book because no one had written about how they got there, what kind of families they came from and what it was like day-to-day. He looked forward to the opportunity to get reacquainted with them.

Trillin’s book was originally published in 1964, specifically so that he could come back to Georgia after Hunter-Gault and Holmes graduated. He said that their story was worthy of a book because no one had written about how they got there, what kind of families they came from and what it was like day-to-day. He looked forward to the opportunity to get reacquainted with them.

“Nonfiction writers are always looking for pieces no one has done before,” he said.

Boyd also asked Hunter-Gault about the sense of isolation both she and Holmes felt during their time at UGA. While she made a handful of friends and spent time with some of her professors, Hunter-Gault pointed out that Holmes never really made friends during his time at the university. After classes, he would go back to the Black family he stayed with and play football with others in the neighborhood. He focused on his studies and graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

Trillin said that could be because of the way Holmes looked at the situation. First, he came from a family that was active in desegregation, and there were great expectations on him. Second, although he went to school at UGA, his life remained in Atlanta, and he returned there on weekends. Lastly, he understood that he was more likely to be physically hurt than Hunter-Gault, so he adopted a sort of “defensive crouch.”

“When we needed one another, we were there for one another,” Hunter-Gault said. “When it was important, we came together.”

‘Wonderful experience’

Boyd noted that Hunter-Gault is treated with a great amount of respect when she comes to back to UGA and asked how she returns to campus without any bitterness about her experiences as a student. The main reason is that she said she had a “wonderful experience,” despite the challenges.

“It hasn’t been difficult for me to come back. In fact, it’s been a pleasure for me, my husband and my children,” she said. “Over the years, Hamilton and I came back many times to remember in the best possible way our experience and what we thought we might have contributed to the institution, opening it up for other students who look like us.”

Boyd asked if UGA has done enough to continue the efforts started in 1961. Hunter-Gault said that the university is putting things in place to do even more to embrace its students of color.

Encouraged by what she sees

“Having the consciousness that it needs to do better, to me, is taking it a long way down the road,” she said.

Hunter-Gault added that she’s encouraged by the students at UGA today, especially the projects they’ve created that are supported through her Giving Voice to the Voiceless fund.

“You’re going to stumble from time to time … but you need to look back at history. Our history is our armor,” she said. “Right there, at the university, we can do things that will help illuminate our issues.”