To walk through the Medical Robotics Lab at the College of Engineering is to witness the inventive and synergistic play of the very bright.

In such an environment, magnetic resonance imaging-compatible medicine is made finer and better. MRI-compatible technologies under development at the lab include the brain biopsy model, catheters, robotic prostate biopsy and electrocardiogram systems.

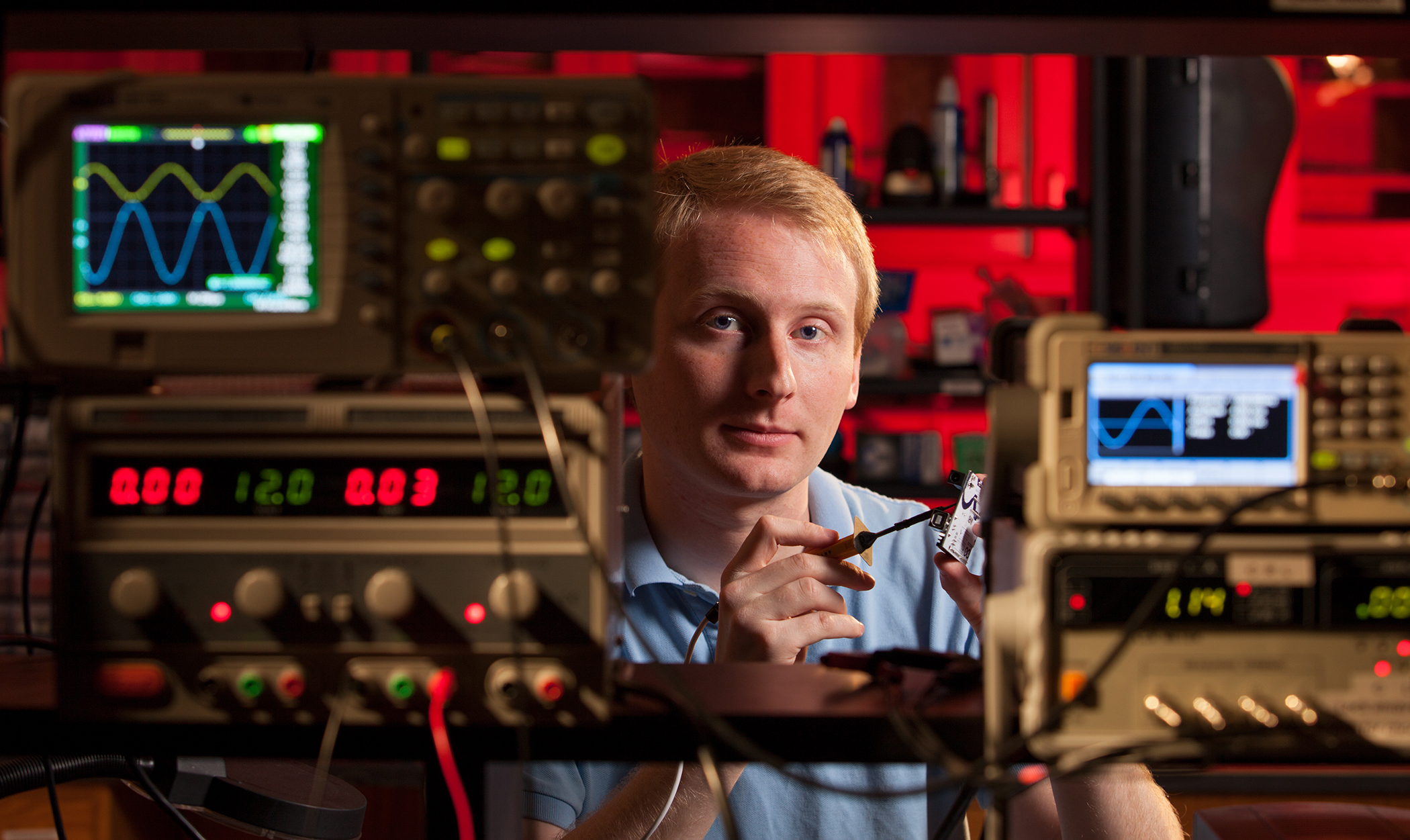

Stan Gregory, a doctoral student in engineering, spends his mornings in the Medical Robotics Lab whenever he isn’t teaching, and sometimes when he is. He’s especially fond of bringing students into the lab to combine both experiences. In fact, he said he gets such a charge from this that he is now thinking of becoming a full-time academician.

Gregory enrolled at UGA after completing his master’s degree at Virginia Tech. For Gregory, who is surrounded by fascinating pieces of fabricated electronics and tools, his decision to come to UGA was specific and personal-not about the gadgetry.

“It’s all about the adviser,” he said.

He headed to UGA based upon one vital piece of information: The reputation of the lab’s principal investigator, Zion Tse. Before transferring, Gregory visited the campus and interviewed the professor to confirm what he hoped-that Tse is a visionary who supports his students.

Tse previously worked for Harvard Medical School Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where he developed systems for cardiac MRI-guided catheter surgery, ECG and surgical navigation. Prior to coming to the U.S., he developed a robotic system to perform prostate cancer biopsy under MRI guidance at the Imperial College of London’s mechanical engineering department.

More recently, Tse was awarded UGA’s Innovative Instruction Grant for his “Do-It-Yourself Approach for Learning Engineering Physiology.”

The research of the UGA Medical Robotics Lab is devoted to MRI. That technology uses a high-powered magnet to construct 2- and 3-dimensional images that are much more detailed. Also, they are safer, as they do not use ionizing radiation.

Unlike CT scans, MRI does not break DNA nor cause DNA mutations. Although human cells nuclei are affected by the electromagnetic field of an MRI machine, all evidence is that they return to a normal state afterward. The challenge, however, is in constricting motion during a scan.

“The problem with the heart and MRI is the physiologic motion,” said Minta Phillips, a Harvard Medical School Fellow in MRI at one of the first three sites GE built for clinical MRI in the 1980s.

The first author to observe that peripheral zone defect is suspicious for cancer, Phillips describes how blood flow and the contracting muscle of the heart create inherent problems in the production of an image. Think conventional photography.

“You don’t want to have motion blur,” she said.

Gregory is working on techniques to address this problem. He specifically studies moving blood flow and imaging via MRI machine. There also is the need for speed-MRI is famously slow.

Inside a place like the lab, better medicine-faster, safer-can evolve.

“Currently, I am studying methods to improve image quality and decrease scan time during cardiac MRI using electrocardiogram (recordings of the heart’s electrical activity) synchronization,” he said.

Lab manager Alex Squires, who is pursuing his master’s degree in engineering, is working to pinpoint the exact location of tumors in veterinary medicine.

A native of Richmond Hill, Squires was the first hire of the new lab in 2012. Like Gregory, he also prefers high interaction with students and fellow researchers. For fun, he advises the Athens Academy robotics team on fabrication and design.

Squires’ project is dedicated to designing a localizer box to help MRI-guided needle therapy in brain procedures.

Squires now is collaborating with doctors at Emory University to develop a tool to more precisely apply therapeutic stem cells into the spines of Lou Gehrig patients.