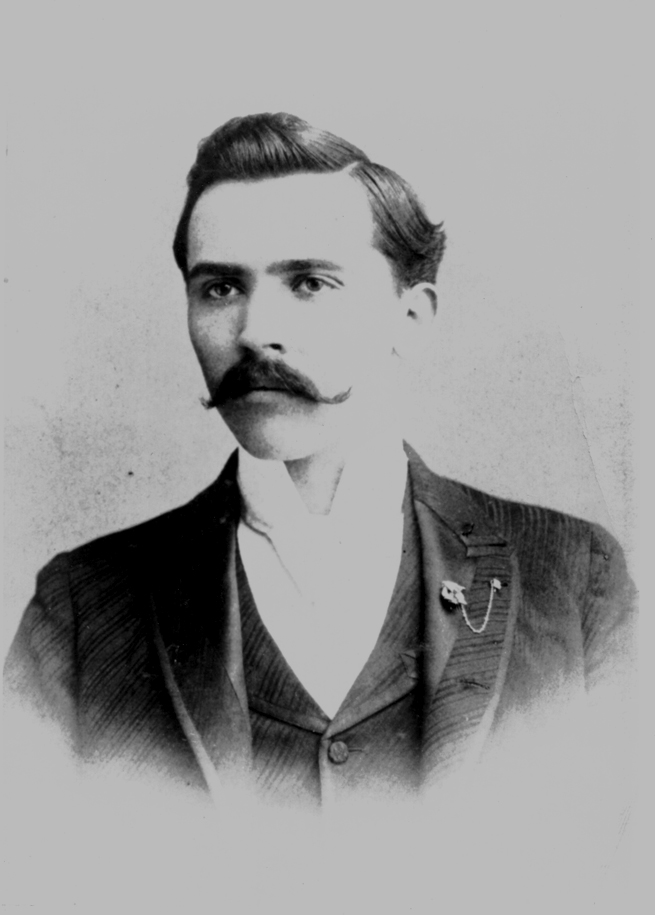

On May 7, 1867, John Hale, the 10th child of Joseph and Elizabeth Hale, was born in Elgin, Georgia, about 20 miles east of Griffin. John grew up working in the fields and listening to his oldest brother William tell stories of serving in the Civil War. As he grew older, John’s heart was set on attending the University of Georgia, where his second-oldest brother Samuel had earned a law degree.

By 1887, he was at UGA, making the most of his opportunity. He was elected president of the Demosthenian Literary Society. He was class poet. And when he graduated with a major in metaphysics and ethics in 1890, he received “the highest honor UGA could bestow.” His was a life brimming with potential.

After a stint teaching, Hale went to medical school and opened a practice in Atlanta. Mixed with professional success, unfortunately, was personal loss. He was twice widowed; his first wife died while giving birth to their fourth child. But by 1918, joy had returned to his family. He had married Annie Schoeller, and they were expecting their first child together.

In the spring of that year, Hale began seeing patients suffering from a particularly devastating type of influenza. The flu came in waves. The second, most severe hit Georgia in the autumn of 1918. By that time, the fast-spreading, highly contagious disease had acquired a name—Spanish flu.

Despite the dangers, Hale continued to treat patients. On Oct. 7, he mentioned to his wife that he felt tired. Soon, he had difficulty breathing and dark spots appeared on his face, telltale symptoms of Spanish flu. Hale knew he was gravely ill, so he quarantined himself, making sure Annie was never in the same room. Instead, his mother-in-law sat with him and made him as comfortable as she could. On Oct. 17, John Hale died. He was 51.

On Oct. 27, Annie gave birth to a healthy baby boy she named Dan.

We weren’t prepared for the pandemic in 1918, and I don’t think we are as prepared for the next one that comes along as we could be, and it will happen,” says Ted Ross, Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar of Infectious Diseases.

UGA professor Ted Ross, Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar of Infectious Diseases, has been working on a universal flu vaccine for more than a decade. He’s had a lot of recent success. Clinical trials for one of the vaccines developed by his lab at UGA are planned to begin in 2019. (Photo by Peter Frey.)

One of the country’s leading infectious disease researchers, Ross came to UGA in 2015 to lead its newly established Center for Vaccines and Immunology. For more than a decade, Ross has fought influenza. The virus, however, is a particularly tricky adversary.

Polio and smallpox—diseases that vaccines effectively eradicated—have limited or no variety of strains. Influenza has many, and they are constantly evolving.

Often, by the time a vaccine is manufactured to tackle a particular strain, it has already mutated, dramatically decreasing the effectiveness of the treatment. That’s what happened in the 2017-18 flu season, a particularly vicious one that saw more than 25,000 flu-related hospitalizations in the U.S.

“What we need to do is target the major subtypes of influenza and come up with a vaccine that recognizes multiple versions,” Ross says. “It may take more than one type of vaccine, but at least we would be broadly protected against the viruses that have shown pandemic potential.”

A century later, historians still don’t know how many people died from Spanish flu. Even the best estimate is so large that it lacks context: at least 50 million. The only comparable pandemic is the Black Death of the Middle Ages.

Spanish flu was worse.

The dreadful conditions faced by soldiers fighting World War I surely added to the death toll, but the front lines in Europe were not where most died from flu. Some rural areas in less-developed nations and colonies lost so many people to the flu they became impossible to count. So they never were. That underestimation has only recently been explored, leading some researchers to raise the number of flu casualties to an almost incomprehensible 100 million.

Even though there is compelling evidence that the flu started on an army base in Kansas, the U.S. wasn’t hit as hard as other parts of the world. Still, 675,000 Americans died from the flu. In places like Russia and China, that figure was likely 20 times higher. Maybe more.

Some 30,000 Georgians died from the flu, but that was less than other areas of the country. The autumn 1918 wave of Spanish flu began in early October at Camp Hancock near Augusta. Military trains brought the virus to camps near Atlanta, Macon, and Columbus before it spread to the cities themselves. At least 800 Atlantans died during the ensuing pandemic, which didn’t fully subside until early 1919. During its worst days, the city did what it could to stop the spread of the disease, and the local government’s bold action surely saved thousands of lives.

Atlanta banned public gatherings, including church services. UGA did its part, too, canceling classes for three weeks until the worst of the wave had passed. Should such a pandemic take place in modern times, could governments and public health entities make similar tough decisions to save lives?

For more than a decade, Ross has been working on what’s been termed a “universal vaccine” for flu. That makes for easy shorthand, but Ross is quick to clarify that even if a vaccine can be discovered to wipe out influenza, it wouldn’t be a single compound that’s injected into everyone.

Instead, a future flu vaccine likely would be a collection of vaccines. The specific type would be given to patients based on a variety of factors including geography, age, medical history, and other criteria. That’s why, instead of “universal,” Ross prefers the term “broadly protected.” He’s had some success, and he’s aiming for more.

In 2016, Ross, in partnership with Sanofi Pasteur, the world’s largest manufacturer of influenza vaccines, announced the development of a vaccine that protects against multiple strains of H1N1 influenza in animal models. Another of H1N1’s strains is Spanish influenza.

Last year, Ross’ lab announced the development of a vaccine that protects against multiple strains of H3N2 influenza. Again, in animal models. Clinical trials in humans for that vaccine are planned to begin in 2019. “The clinical trials will be important because we have to see how these vaccines work in humans,” Ross says.

After John Hale died, his widow Annie was inconsolable. She didn’t attend his funeral. Her mother, wanting to protect her daughter, destroyed many of John’s photographs and burned most of his papers, including his poetry. She wanted Annie to look forward.

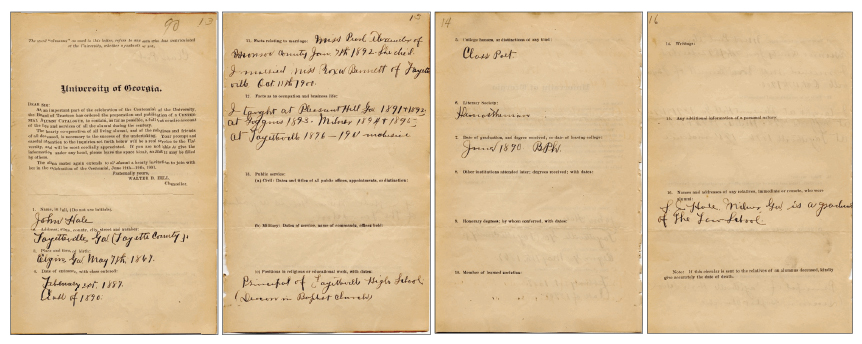

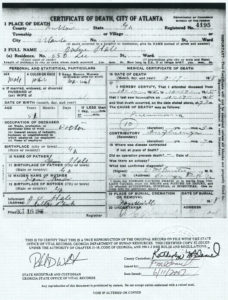

Still, despite her understandable efforts, mementos of John Hale remain. His death certificate is one, listing “pneumonia” as the cause and “influenza” as contributory—as millions of Spanish flu cases ended. Also surviving: a four-page handwritten contribution to UGA’s 1901 Centennial Alumni Catalogue.

Above: John Hale’s death certificate. The cause of death is in the right column. Below: Hale’s handwritten contribution to UGA’s centennial celebration in 1901.

These pieces and a few others are held dear by Laura Bennewitz ABJ ’73, MA’75, Dan Hale’s daughter. Bennewitz’s grandmother, Annie, told her many stories about her late grandfather, John, and while neither she nor her father ever met him, they have always kept his memory alive. Bennewitz,

who lives in Watkinsville, helped carry on his UGA legacy, too. She is one of five of John Hale’s descendants to graduate from the University of Georgia.