Hard-boiled eggs tainted with listeria. Romaine lettuce harboring E. coli. Ground beef laced with salmonella. Raw oysters contaminated with more disease-causing bugs than you can count.

Those are just four of the thousand-plus foodborne outbreaks of illness in the United States in a given year. Contaminated food products make tens of millions of people sick each year, result in thousands of hospitalizations, and cause more than 1,300 deaths annually, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And that’s just in the U.S.

It’s the University of Georgia Center for Food Safety’s mission to prevent those outbreaks before they happen.

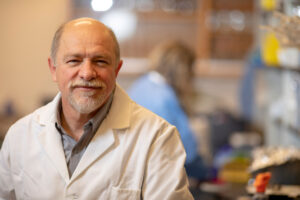

Food safety is critical for the overall well-being of a country or society. We’ve been able to progress in part because we make sure that we don’t get sick from what we eat.” — Francisco Diez-Gonzalez, director of UGA’s Center for Food Safety

Led by director Francisco Diez-Gonzalez, the Griffin-based center, which is part of the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, conducts research on foodborne pathogens and finds ways to minimize the risks they pose to people. The center has eight faculty, including Diez-Gonzalez. But for such a small academic unit, Food Safety’s expertise is broad, with experts on everything from detecting and reducing dangerous microorganisms during the food handling process to the study of parasites that hitch a ride on the fresh produce people consume.

Or, as Diez-Gonzalez’s son used to say, the center’s scientists are fighting “very dangerous bugs” that make people sick when they eat contaminated food.

Over its 28 years, the center has developed close ties to the CDC, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the FDA, and industry partners that include everyone from General Mills to McDonald’s to Publix.

Over its 28 years, the center has developed close ties to the CDC, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the FDA, and industry partners that include everyone from General Mills to McDonald’s to Publix.

“Food safety is critical for the overall well-being of a country or society,” says Diez-Gonzalez. “A century ago, a lot of people were dying from gastrointestinal diseases because of poor hygiene and food safety practices. We’ve been able to progress in part because we make sure that we don’t get sick from what we eat.”

Disease on Ice

Five years ago, 10 people were hospitalized in four states and three of them died after eating ice cream tainted with listeria, a species of bacteria that typically causes fever and diarrhea but can pose significantly more risk if it spreads beyond the gut.

UGA scientists like Henk den Bakker isolate and track the different strains of bacteria like listeria, using computer programs to map the dangerous outbreaks and find connections between bacterial strains and the populations they infect. The algorithms help him determine how and why strains of listeria are able to adapt and become resistant to common sanitizers and what researchers can do to overcome that hurdle.

Bake It Away

You probably don’t think of the flour coming straight out of the bag as raw. It is.

And unless it’s cooked, it can carry germs such as salmonella and E. coli. But how many of us are guilty of licking the spoon from that bowl of cake batter or popping a piece of raw cookie dough into our mouths, putting us at risk of infection?

Research led by Francisco Diez-Gonzalez and post-doctoral researcher Fereidoun Forghani showed when manufacturers treated flour with heat and stored it at about 95 degrees for a couple of months, the levels of bacteria dropped significantly.

Bad Berries

When she first spotted it, Ynes Ortega was a microbiologist at the University of Arizona. She was focusing on children with diarrhea in the shantytowns of Lima, Peru. They were obviously infected with a parasite—one with striking similarities to toxoplasma, one of the world’s most common parasites.

But it was something she’d never seen before. And it seemed to only be causing illness in certain developing countries at first. But then it started showing up in the U.S. in the 1990s, apparently hitching a ride on imported raspberries from Guatemala every summer and giving people who ate the fruit a nasty case of diarrhea that could last for weeks.

She named it Cyclospora cayetanensis.

Fast forward a couple of decades, and the parasite started showing up in American-grown produce, meaning it now may have a stronghold in U.S. soil and other nations.

Fast forward a couple of decades, and the parasite started showing up in American-grown produce, meaning it now may have a stronghold in U.S. soil and other nations.

Cyclospora is a tough adversary and almost impossible to kill. That’s why Ortega is seeking better ways to detect the bug and determine the source of outbreaks. At the same time, she’s also rooting out where the parasite dwells during the offseason months before outbreaks start like clockwork in the summer.

Containing COVID-19

After news broke of a coronavirus that was rapidly infecting people in China, Malak Esseili knew immediately that people would have questions about the safety of their food. How long does it survive on the plastic wraps around chicken? Can it live on the surface of leafy greens? Should people wash their groceries with soap?

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the U.S., infections at meat processing factories quickly skyrocketed. Some plants temporarily closed due to exposure. Meat shortages became an issue. Food safety experts were concerned both about the factory workers’ conditions and how the pandemic would affect already strained food supplies.

Esseili specializes in food virology, focusing on how contaminated foods can serve as vehicles for infecting the people who eat them. Previously, the assistant professor worked on a team at Ohio State University that was trying to develop a vaccine for a different coronavirus that hit the swine industry in 2013.

She quickly adapted her lab’s work to include the novel coronavirus, with the goal of determining how the food industry can protect its workers and consumers from the virus. Esseili’s lab continues to focus on determining how long the virus can live in the environment and on surfaces of food and food packaging, as well as which inactivation strategies are the most effective at destroying the virus.

Research Areas at the Center for Food Safety

Food Safety Bioinformatics: Applying advanced technology applications such as whole genome sequencing, machine learning, and data analytics to solve foodborne pathogen contamination issues.

Antimicrobial Interventions: Developing novel technologies and ingredients to inhibit or inactivate microbial risks in fresh fruits, vegetables, and grains.

Food Microbial Ecology: Advancing the understanding of pathogen interaction and survival in food-related environments, in particular the control of salmonella in poultry.

Pre-harvest Food Safety: Targeting the control, elimination, and detection of foodborne pathogens before crops are harvested or livestock is slaughtered.